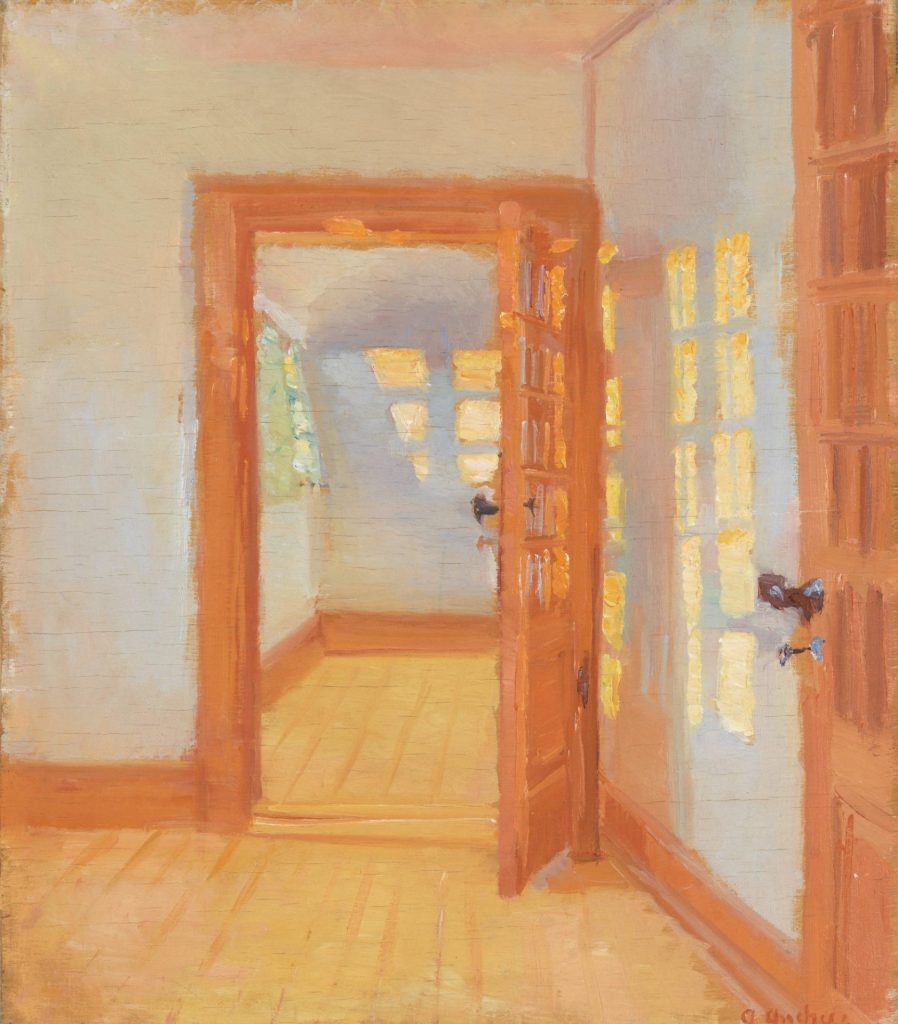

Modestly sized and sparingly figured, Evening Sun in the Artist’s Studio at Markvej is an unassuming highlight of Dulwich Picture Gallery’s exhibition dedicated to Anna Ancher, regarded as one of Denmark’s greatest artists. Painted at some point after 1913 and found unframed after her death in 1935, in the house she had shared with her late husband, the painter Michael Ancher, the painting was never exhibited in her lifetime.

Made in old age, when for the first time in her career she had a studio of her own, this quiet painting is a remarkably eloquent statement of Ancher’s artistic project. Seen from a distance, it can be understood less as a portrait of a remarkably uncluttered studio, and more as a semi-abstract composition of form and colour.

In it, the complementary colours blue and orange, reminiscent of Monet’s celebrated canvas Impression, Sunrise (1872), contrast and absorb each other across the piece in a virtuosic display of painterly effects. Some pictures, only loosely described, lean against the wall.

In the foreground, almost disappearing beyond the frame, is the end of a cabinet, or bookcase, flashed with orange, and a small table on which two books balance unsteadily. The table itself is so insubstantial that at points it seems ready to melt into the background; its pedestal actually dematerialises at one point, the brushstrokes stopping short, then resuming at the oddly animal-like legs. Here, Ancher suspends illusion just for a moment, as she terminates the table legs in nothing more than splashes of paint.

Ancher was born in 1859, a decade after her husband. They were part of a group known as the Skagen painters, who gathered in this fishing village at Denmark’s most northerly point each summer. In thrall to the French impressionists and realists, most were attracted by long evenings on Skagen’s beaches, and especially by the “blue hour” in which water and sky seemed to merge. For Anna, this beauty was in her DNA: she was the only one of the group to have grown up there.

Ancher’s greatest trick, which recurs again and again in her work, is to make pure light the most unequivocally material element of the whole composition. Her preoccupation with light was hardly unusual among painters of her generation, but in rendering it in thick impasto, often in contrast to her barely-there treatment of bricks and mortar, she pushes beyond naturalism to explore painting as a subject in itself.

The exhibition includes more than 40 paintings, most of which are on loan from Denmark’s Skagens Museum, a reflection of Anna’s iconic status. For the five years between 2004 and 2009, she and Michael featured on Denmark’s 1,000-kroner banknotes, the highest denomination.

Ancher (née Brøndum) was still a child when she first got to know the painters who came to Skagen in the 1870s, staying in Brøndum’s Hotel, owned and run by her parents. Her future husband gave her painting lessons, and by the time she was 15, and enrolled in a Copenhagen art school with the support of her mother, she was already very much a part of Skagen’s growing artist colony.

Though Ancher was fortunate enough to have a husband and family who supported her career, society was then unused to the idea of women’s careers, and the birth of her only child, Helga, in 1883, brought a letter from her old teacher in Copenhagen, advising her to throw her paintbox into the sea.

Instead, and with her family stepping in to look after Helga, Ancher and her husband travelled to Paris in 1885, going again in 1889, when they stayed for six months, and Ancher took lessons with Puvis de Chavannes, one of the most revered painters in France. The trips followed an earlier tour of Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and Munich.

No work seems to have survived from these travels, but their impact was great – the Dutch masters seen in Vienna evidently inspired The Maid in the Kitchen (1883/1886), and the lessons she learned from Impressionists, some of whom subsequently made the trip north to Skagen – made their way into her paintings of the locals and landscape.

Suggested Reading

Wes Anderson’s dollhouse world

Compared with the subdued palette of early portraits, such as Stine Bollerhus Counts the Money Earned Selling Bread (1879), her post-Paris Sunlight in the Blue Room (1891) reverberates with pure colour, made more vibrant still by her use of complementary colours.

Domestic scenes and portraits of villagers remained favourite subjects. Some of her best paintings are of old people, the cheery Old Couple with Their Rabbits (1891/93), animated by joyful affection. In contrast, Three Old Seamstresses (1910) is a study of silence; at work on a beautiful dress, presumably for a younger woman, it is easy to imagine their thoughts going back to their own youth. Here, as so often in Ancher’s work, substance is fleeting as puffs of blue fabric and a ceramic pot dissolve in sunlight.

Ancher’s tendency towards the metaphysical took a more mystical turn later in her career, the symbolist resonance of Grief (1902), reminiscent of allegorical figures by Van Gogh and Munch. Fireworks on Fyrbakken (undated) feels bleakly existential, reducing her life’s work to its element – light.

Anna Ancher: Painting Light is at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until March 8