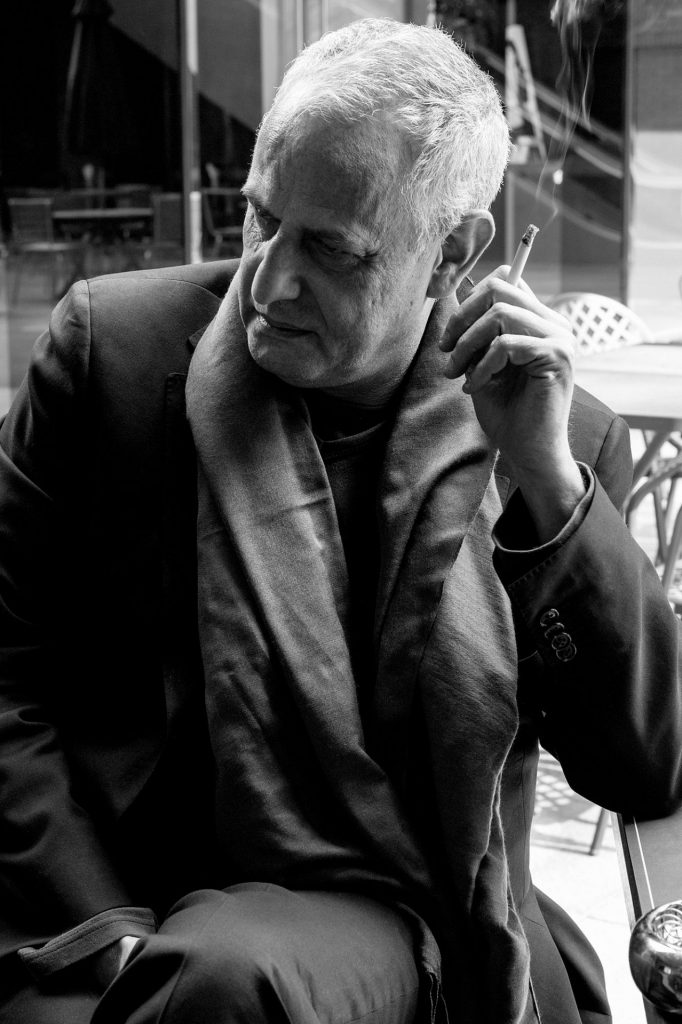

Finishing his cigarette on the steps of the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, Belgian artist Luc Tuymans has retained the formidable bearing that in his youth must have made him a handy bouncer. Today, veiled in a fine drizzle, his voluminous, long black coat adds a mildly ecclesiastical touch – fittingly so, since papal intrigue is in the air: later that day, white smoke issues from the Vatican.

The film Conclave is “a disappointment, to be honest” says Tuymans, 66, stepping past a noirish publicity portrait, and into the 16th-century church, designed by Andrea Palladio for the Benedictine monastery that has occupied this little island since the 10th century. For the next few months it is home to Heat and Musicians, two paintings specially commissioned by the monastery and German-Dutch non-profit art museum the Draiflessen Collection, to occupy the space temporarily vacated by Jacopo Tintoretto’s The Last Supper and The People of Israel in the Desert, as they undergo conservation treatment.

Installed high up in the presbytery, the paintings remain hidden from view until the last moment, when flashes of fiery, almost neon red, flicker into view, countered by pools of darkness and blue from Musicians, hanging opposite.

Musicians was inspired by a bad hotel band in Busan, whose distorted, spectre-like reflections the artist captured on his iPhone. It evokes the pale cold light inside the church, and as such is the direct opposite of Heat, which depicts a hugely magnified detail of a thermal lamp, of the sort often installed in churches – “always cold” – in the winter. “I had this idea that one image would disintegrate the other,” he explains.

Tuymans has always explored our collective sore points, and since he came to prominence in the 1990s, he has delved into global politics, and the reverberations of historical traumas, from colonialism to the Holocaust. This collaboration with the Catholic church, just as it finds itself at the top of the global news agenda, is entirely true to form, but it’s the unique setting that has caught his imagination.

“I have a very complicated relationship with the Renaissance,” he says, pointing out that his native Antwerp is associated with High Gothic. “For me, the Renaissance is absoluteism. It’s no wonder that when the colonnade of Bernini [the Palazzo di Propaganda Fide in Rome] was finished it was also the first time the word ‘propaganda’ cropped up.

“I see the Renaissance in terms of, let’s say, warlords basically, mafiosi. And in that sense, the idea of power – earthly power – is a different one from spirituality. All these things, these fascinations, come together here.”

The church of San Giorgio Maggiore is a Renaissance jewel, and its remarkable artistic lineage reaches back to the 16th century when Tintoretto made three paintings for the abbey, and collaborated on two more with his son Domenico. There are paintings by Sebastiano Ricci and Jacopo Bassano, and, Tuymans tells me that in a serendipitous connection across time it was one of his countrymen who crafted elements of the magnificent original woodwork.

Suggested Reading

The museum that delivers

Over the past decade or so, Benedicti Claustra Onlus, the non-profit branch of the Benedictine Community of San Giorgio Maggiore, has commissioned artists including Anish Kapoor, Sean Scully, Not Vital, Berlinde De Bruyckere, and now Luc Tuymans, with the intention of reviving what Abbot Stefano Visintin calls the “fundamental bond between church and art.”

While not devotional in the manner of the Tintorettos they replace, the reflections of Tuymans’s paintings captured in the copper globe at the centre of the high altar offer a visual metaphor for the process of meditation and personal reflection that the project seeks to inspire. In the current climate, this feels like a vestige of a progressive era, whose passing coincides with that of the late Pope Francis, who last year declared: “The world needs artists.”

The election of the moderate, continuity Pope Leo XIV has dispelled immediate fears of an impending Dark Age, but the community at San Giorgio Maggiore stands for a liberal-mindedness that is increasingly rare in the wider world.

“We’re living in this extreme turmoil, due I might say, particularly to one specific person who was actually able to even take away all the attention at the funeral of the pope by putting two chairs together (he means Donald Trump). You have a number of very delusional people who are over 70 who are fucking up the globe. So this, is interesting,” says Tuymans, gesturing towards his paintings, “in that it parallels that moment in time, in this specific setting – I mean, the abbot was actually in Rome for the funeral of the pope, as we were putting the canvases on the frames.

“The United States is destroying everything that I basically stand for, and a lot of Americans that I know do, too”, he continues. “The silver lining is that this is the exact moment when Europe should get it together. It’s a historical moment, that will force them into finally making decisions after ages of complacency. That’s something that Trump unintentionally triggered in a very weird way.”

Now, he says, the danger lies not so much in change, but in its rapid onset. “When it’s done in a rational way it actually could be beneficial. But it is going at a speed which is not in step with what we can take in, which is dangerous, to say the least.”

In this misalignment of reality and our perception of it, the digital realm is of pivotal importance and of special interest to Tuymans, who has always been a visual magpie, and now includes YouTube, his iPhone, and AI among his tools. But while AI is “great for surveillance, medicine, all those things that have to do with control,” it does best with closed circuits: “Once you

lose the closed circuit… this is the beauty of painting, of course, also the fact that you can make a painting as big as you want.”

He means physically big, but it’s a conceptual point too, that makes a virtue of uncertainty, the grey areas that in Tintoretto’s age were negotiated through faith. Painting, says Tuymans, is a function of “human limitation, which I think is the most aesthetical and ethical point of view that you can have within the idea of representation. That and to accept failure, but try to understand – or at least doubt things. This is what the work is all about.

That’s the aim.”

It’s a view of painting and the creative imperative that collapses the centuries, as surely as his retreating footsteps echo those of all the artists who were ever here before.

Luc Tuymans: Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice until November 23, 2025. Florence Hallett is an art writer who lives in London.