A black and white photograph from 1971 shows the Italian artist Ketty La Rocca in bed, gazing at a large, plastic letter “j” that lies next to her, under suggestively rumpled sheets. It’s titled With Unease, and it’s true that I – and perhaps you too – would feel uneasy in her position.

La Rocca’s unease goes further, though. In Italian, the letter “j” is so rare as to be almost redundant. More than an inadequate bedfellow, La Rocca’s “j” stands for the failure of language to express the complex emotions and sensations so eloquently transmitted in her own body language and facial expression.

The “j”, in all its awkward, plastic pointlessness, makes an impotent proxy for language – so much so that it doesn’t matter that it is back to front, as it is in the photograph, and now in the Estorick Collection where J (Three Dimensions), 1970, features in an unprecedented exhibition.

The exhibition’s title is You, You, words that echo through La Rocca’s works from the 1970s, like a voice not heard, or an unanswered prayer, capturing the yearning melancholy that infuses even her wittiest creations.

Staged in close collaboration with La Rocca’s family, this first UK museum show to be dedicated to this little-known hero of Italian conceptual art does not dwell on the artist’s death from cancer in 1976, aged 37. It hardly needs to – her career barely spanned the two decades of the 1960s and 70s, and the sadness of a life cut short, and a small boy left without his mother, spreads across her legacy like a stain.

La Rocca was born in 1938 in the port city of La Spezia, Liguria. A decade later, the family moved to Florence, where she lived for the rest of her life.

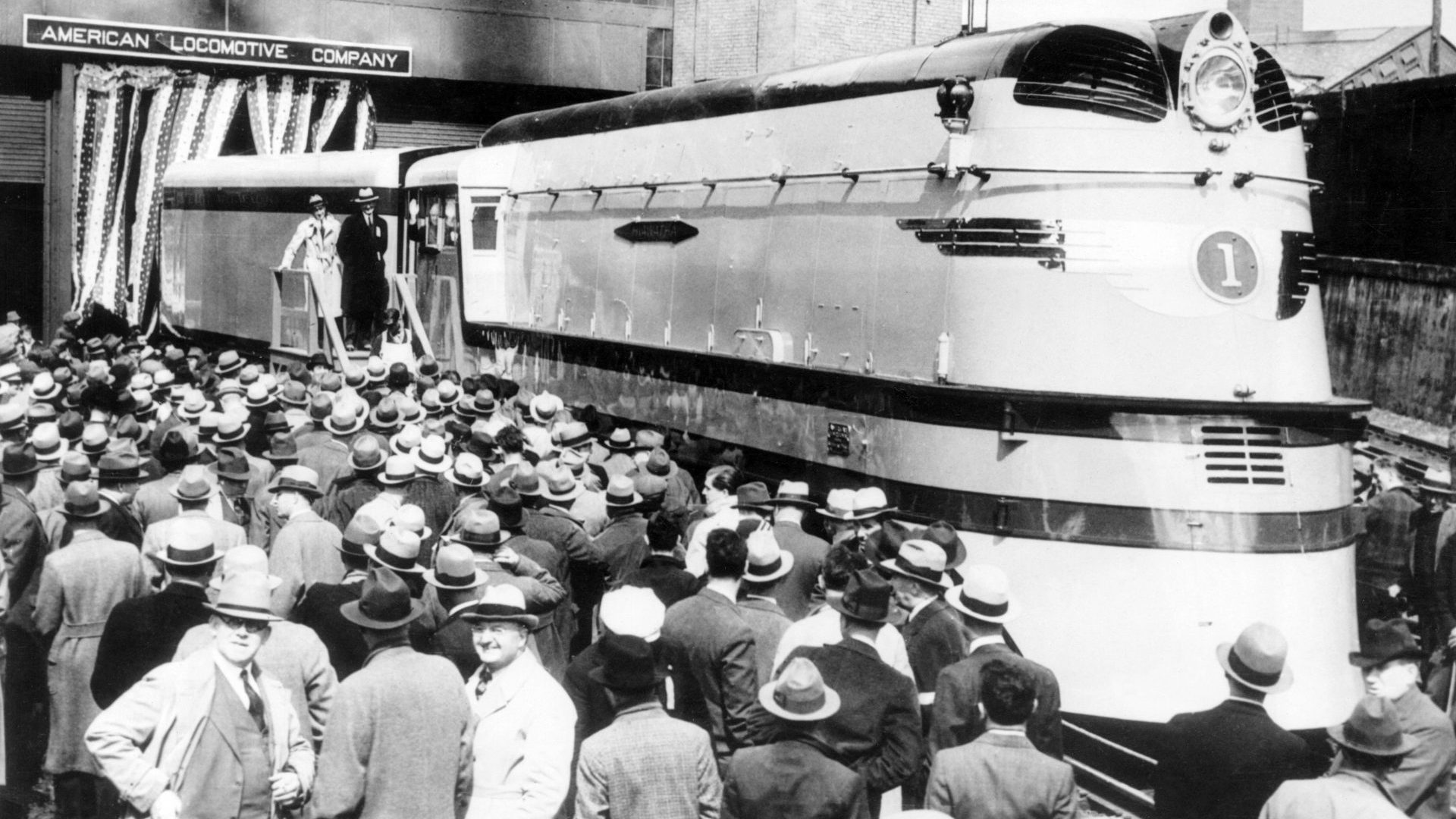

Florence is a city that tends to be thought of as too conservative, and too absorbed by its Renaissance past to foster modern and contemporary art, but in the period just after the second world war, a thriving avant-garde scene mixed left wing politics with the consumer culture and technological advancements of a buoyant postwar era. In these years, the city represented in microcosm a struggle that played out across the whole country, its ancient heritage and culture at odds with the rapid industrialisation that fuelled Italy’s economic miracle.

In the early 1960s, La Rocca was a schoolteacher, but her interest in electronic music, and poesia visiva, the visual poetry that continued the wordplay of René Magritte, among others, brought her into contact with Gruppo 70, Florence’s most progressive art collective.

Suggested Reading

The triumph of ‘nobody’s darlings’

The exact extent and nature of La Rocca’s involvement is unclear, though the volume of collages she made before Gruppo 70 disbanded in 1968, and her Veline (Tissue Papers) – miraculous survivors from a 1967 performance – suggest that it was considerable. The scraps of pastel-coloured paper, printed with cryptic snippets of text – “who has news of Patrizia Vicinelli?”; “the car has optimum performance” – were handed out on the streets of Florence, like tiny poems, or prompts.

Gruppo 70 favoured the clever positionings of text and image that La Rocca uses to make trenchant comments on the representation of topics in the mass media, from the treatment of women to the Vietnam war and racial inequality.

In one of her most sharply witty collages, a procession of identical, proper-looking, umbrella-carrying businessmen approach a nude woman, who lies seductively across the image. “Non commettere sorpassi impuri” reads the caption (“Do not overtake improperly”), a rebuke that belittles the men and draws a stark comparison between male and female stereotypes, and the power imbalance between them.

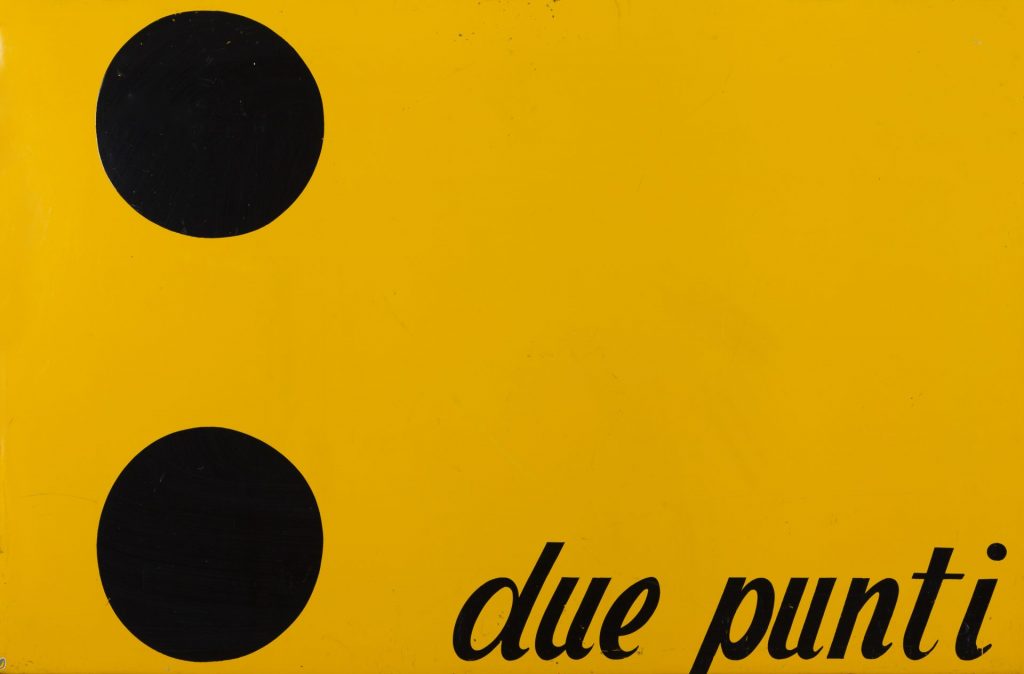

She subverts the clarity expected from signs, especially road signs – themselves a postwar initiative, introduced following the 1949 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic – to favour ambiguity, and poetry, as in her 1968-69 “road sign” that points the way to Vasta Eco (Vast Echo).

The 1970s saw her shift further towards this more refined, poetic way of working, captured in a beautifully embroidered cushion from 1975. Here she uses a gentle, “feminine” craft to describe the gross distortions of the gender divide, represented in beautiful but destructive encounters between birds and aeroplanes.

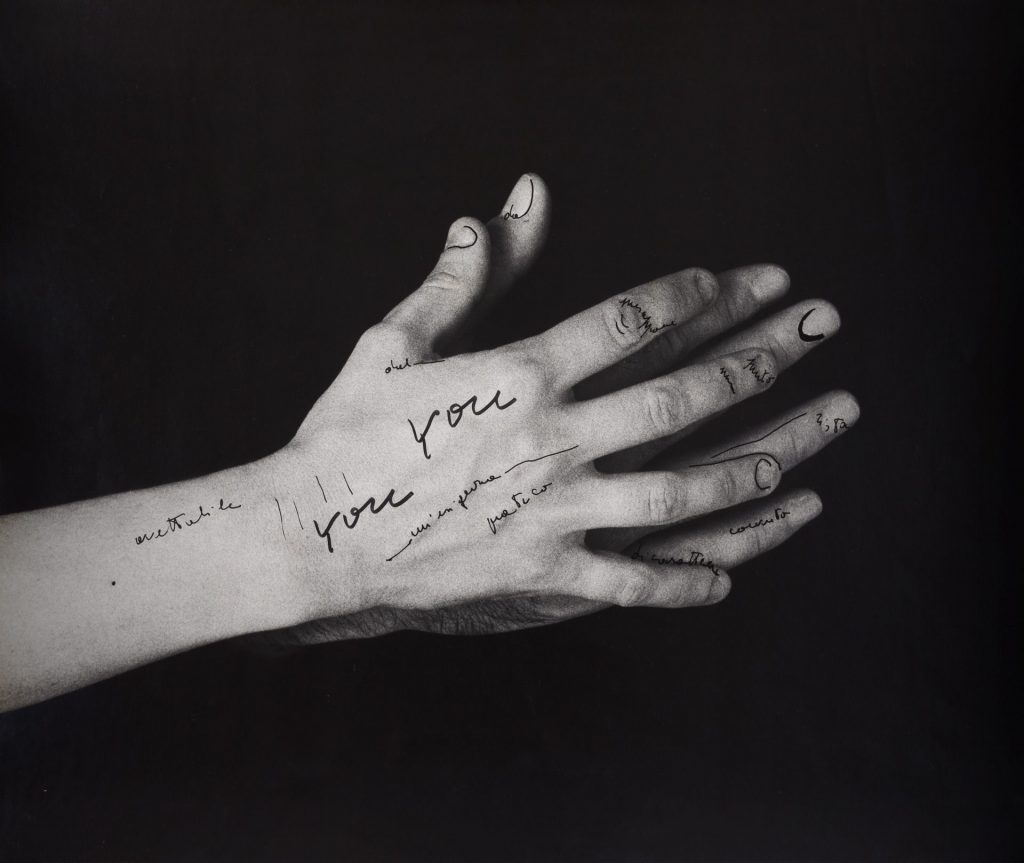

Hands became an increasingly important motif for La Rocca in the 1970s, in works that through combinations of photography, drawing and writing explore the possibility of an unmediated language of the body. In her 1971 series Le mie parole e tu (My Words and You), the forms and lines made by her hand, placed against her husband’s, create an intimate language of their own.

Her handwriting across contours and lines is ambiguous – as if this bodily language she has created needs substantiating with words. And yet, “you, you”, written again and again mostly seem to mark traces of a loving touch.

This idea becomes more intense and ambiguous still in the artist’s Craniologia series from 1973. Though unconnected with her own illness, the medical nature of these X-rays of a human skull, annotated with “you, you”, inevitably feel grimly existential. Superimposed with images of hands and fingers, that relentless chant of “you, you” seems to lament the ultimate unreachability of others, however much we love and know them.

Ketty La Rocca: You, You is at the Estorick Collection until December 21