Turin to Sarajevo is a journey of about 26 hours by bus. Once you cross the border from Croatia, a landscape of overwhelming natural beauty unfolds in front of your eyes. Minarets rising above the mountains, neatly cultivated fields, wild rivers flowing through high limestone gorges and apparently untamed forests. Wherever you look, signs warn: “Do not leave the paths, danger of mines”.

The shadows of the tragedy that overwhelmed this region between 1992 and 1995 are everywhere. Crossing from Croatia, you enter Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also Republika Srpska, one of its three divisions. It is a land that many Serbs regard as part of “Mother Serbia”, their home.

The flag of Republika Srpska is displayed everywhere. Outside small cafes along the street, on government buildings, hanging from the windows of private homes. This does not make it easy for Bosnia to remove the ghost of war, nor does it help its long journey towards joining the European Union, which began in February 2016 after it was officially recognised as a “potential candidate” country.

Taking in the magnificent beauty of the landscape and feeling the weight of the past, memories come flooding back. Past trips, before and after the conflict.

My father, holding me in his arms in Mostar in the summer of 1989, as we stopped to watch, enchanted, the divers of Stari Most (the old bridge) throwing themselves from a height of 24 metres, honouring a 500-year-old Ottoman tradition. The TV images of those mortar shells tearing through the market in Sarajevo, the horror of the mass graves around Srebrenica, the cold in Prijedor in the winter of 2011 and a final trip to the Balkans in 2014.

Sarajevo, first stop on this journey, is the symbolic site of the conflict, during which the city suffered the longest siege in the military history of the late 20th century. From April 5, 1992 to February 29, 1996, in a fully isolated city, the artillery bombardments became exhausting. Serbs were everywhere and the shout “Pazite, snajper!” (“watch out, sniper!”) echoed in every street.

I’m back in Bosnia for the commemorations of the 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide. One of the darkest chapters in European history since the second world war, with Europe still struggling today to acknowledge its guilt in the co-responsibility for this genocide.

In July 1995, the Drina Valley was overwhelmed by the homicidal rampage of Ratko Mladić’s Serbian militias. This was despite the fact that the city had been declared a “protected area” by the United Nations in April 1993, and was under the protection of a small Dutch army contingent commanded by Thom Karremans.

On July 11, Ratko Mladić’s paramilitaries entered the city without facing any resistance. Among the approximately 40,000 people who were in Srebrenica at the time, there was total panic. Thousands escaped into the woods.

Hundreds of families were handed over to the militias by the blue helmets as Karremans negotiated with Mladić to secure the fate of the civilians. He failed, and the Dutch troops either ignored or were powerless to stop the violence and killing that was already under way.

Hundreds were transferred to refugee camps. Many women suffered sexual abuse by the Serbian troops, who used rape as a weapon of war.

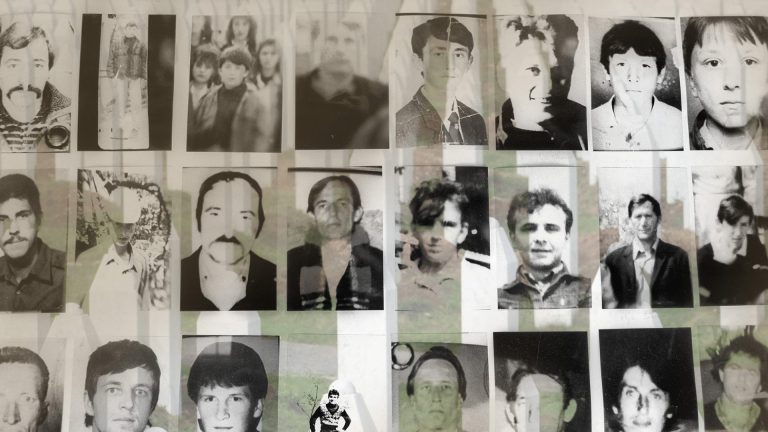

Thousands of male prisoners, captured together with those who ran away into the woods, were killed in the following days, systematically. Their bodies were buried and hidden in several mass graves, then moved multiple times to hide these war crimes.

Over time, this made it more difficult to identify the more than 8,000 victims, a task undertaken by the ICMP (International Commission on Missing Persons). In a laboratory next to the Komemorativni centar Tuzla in north-eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vučetić has been working for more than 20 years, analysing the skeletal remains that arrive on her desk.

Suggested Reading

Bosnia’s enduring pain

This trip to Bosnia reminds me at every step that its wounds have not healed at all and that the Dayton Accords, signed in November 1995 with the aim of ending the war, have frozen in time a situation that is becoming increasingly fragile in a nation with a complexity that is difficult to portray. It’s a land where very disparate peoples, cultures and religions have coexisted for centuries, with ethnic minorities spread everywhere.

The people I spoke to were completely disaffected with current politics, convinced that Bosnia’s muddled system, based on an architecture of parliaments, governments and presidencies, is now responsible for chronic immobility. This has nothing, they said, to do with a genuine desire to bring unity to the nation.

The only unity I found was during an evening of traditional folk music at Kino Bosna, one of Sarajevo’s most peculiar clubs. Benjamin Čengić, founder of the street artist collective Obojena Klapa, greets me with a sentence that stays with me for the rest of the trip: “Power positions create villains”.

Federico Tisa is a documentary photographer from Turin