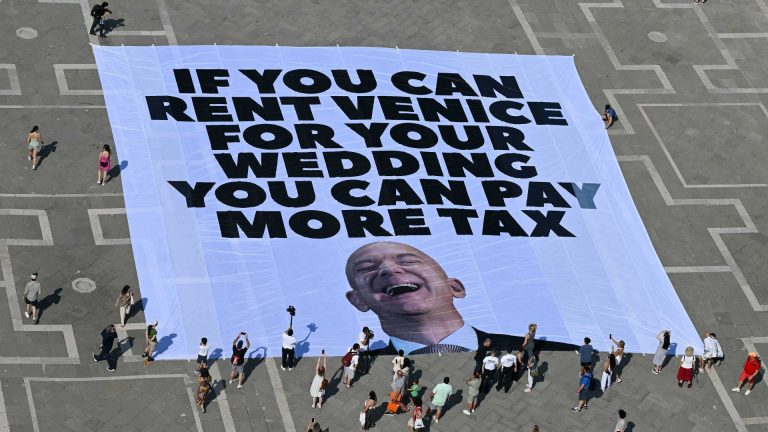

What kind of a world do we live in? One of the richest people alive hires substantial parts of Venice, against many Venetians’ will, as a backdrop for his exclusive, extravagant, and somewhat tacky wedding party. That must have cost $50m. Meanwhile, Amazon is criticised for its gruelling conditions, disdainful attitudes towards workers, and its low rates of pay.

How many Amazon warehouse workers cheered Jeff Bezos and thought the money well spent? I guess many of them sympathised with the Venetians who planned to block canals with inflatable alligators and who launched a dummy of Bezos clutching cash and an Amazon package into the waters.

Bezos, though, is just one extreme example. Many of the rich and powerful delight in displaying their wealth and power in frivolous ways even though they know children they could easily help are dying of hunger elsewhere.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose birthday was June 28, published his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality in 1755. This extended essay, written for a Dijon competition, was a response to the prompt “What is the origin of inequality, and is it authorised by natural law?”

Rousseau was a contrarian. In an age celebrating progress he took the line that civilisation brought many ills.

In the previous century, Thomas Hobbes had described the state of nature as one in which individuals were in a perpetual war against one another with rational grounds for making pre-emptive attacks against their neighbours. Human nature for Hobbes was fundamentally selfish: without a powerful sovereign to make them keep promises and ensure punishment for wrongdoing, people would literally tear each other apart.

Rousseau rejected the idea that we would be merely selfish in the state of nature. True, savages would be driven by what he called “amour de soi”, an instinct for self-preservation, as we all still are. But they would also have a capacity for compassion, an aversion to seeing others’ suffering – that’s part of human nature too.

In place of Hobbesian man living in perpetual fear of attack, he imagined noble savages as lone, self-sufficient, unreflective individuals, wandering through the forests living a contented animal existence, with no desire to harm others. They wouldn’t have language or the need for it. Reproduction would be functional, pairing brief and without commitment. Their only reason for conflict would be when their lives were threatened.

Suggested Reading

Venice cannot be bought, Mr. Bezos

What happened to these content but unreflective savages as they gained the power of rational thought and developed language, formed groups, and, most importantly, acquired possessions? Rousseau’s savage spends a lot of time alone, and when he or she encounters others, lacks the incentive or mental wherewithal to make comparisons.

But with language, possessions, division of labour, civilisation, that all changes. Comparisons feed a desire for visible self-worth. Whoever was the first to enclose a bit of land and call it “mine” had a lot to answer for.

After that there was no going back. Ownership was an important catalyst for a new kind of self-love, different from amour de soi. Rousseau labelled this “amour propre” – sometimes translated as “pride”.

Amour propre is an emotion that arises when humans live together in close proximity. It’s a desire to compare ourselves with our neighbours, and a special kind of pleasure in showing that we are better, richer, more powerful, than them.

Bezos’s performative wealth, conspicuous consumption, and apparent indifference to the social inequality in which he plays a key role, is the latest example of this. This looks like a morally corrupting example of amour propre.

For Rousseau this is an inevitable consequence of progress away from our natural state. Put human beings in groups and they’ll compete with one another. Delight in inequality will then be rife among the better off.

Suggested Reading

Who’s been mocking Jeff Bezos’s nuptials?

Many of his contemporaries considered Rousseau’s description of life in a state of nature sentimental: the reality would be grimmer, more Hobbesian. Voltaire said his reaction to reading the Discourse was to be seized by a desire to walk on all fours, but that after 60 years walking on two legs he couldn’t bring himself to go back to crawling.

Yet Rousseau wasn’t arguing for a return to a savage existence. He was diagnosing the status quo. The notion of amour propre is a useful starting point for that today, even if Rousseau was over-optimistic about human nature. How else to explain absurd, insensitive displays of wealth like last week’s Venetian wedding?

If Rousseau is right, though, it’s not just Venice and Bezos that are sinking. We all are.