On the night of November 13, 2015, Paris was attacked at its heart. Islamic State jihadists, most of them born and raised in France, stormed the Bataclan concert hall, killing 90 people, while coordinated shootings and bombings at cafés and the Stade de France brought the death toll to more than 130. It was the bloodiest night in France since the second world war.

Now, on the tenth anniversary of the attacks that reverberated around the globe Des Vivants (The Living) brings viewers back inside that horror – but from a radically human angle focused on a small group of survivors. The eight-part series, made by the France 2 channel, tells the true story of hostages trapped for more than two hours in a narrow corridor beside the concert hall, face to face with two armed terrorists wearing explosive belts, until their ultimate rescue by 18 French tactical counter-terrorism forces.

All 11 survived, and seven of them went on to become friends (two members of the group were already a couple with children), making their first contacts with each other in the days after the terrorist strikes. As they later admitted: “We owe our lives to each other.”

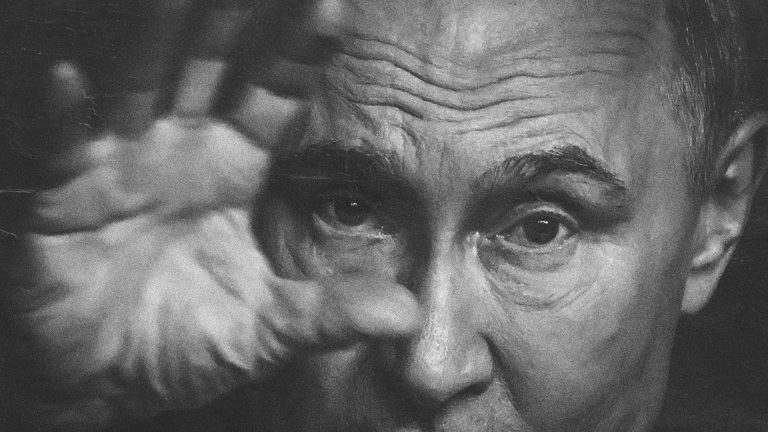

“They walked out alive,” said the series creator and director Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, best known for the Oscar-winning documentary Murder on a Sunday Morning, about the tangled aftermath of a murder in Florida. “But alive how?

“What does it mean to be alive after such a traumatic and extreme experience, one for which no one can ever be prepared? And how can you reclaim your own story when your tragedy has become that of an entire nation?”

As he told France 2, when producers first approached him in 2023, he hesitated. “I thought I’d already ploughed enough tragic ground. But I realised this story asked something essential: what does fiction owe to reality when faced with the unnameable?”

De Lestrade met each of the real survivors who agreed to speak to him — who call themselves les Potages, a contraction of potes (mates) and otages (hostages) — and built his script entirely from their testimonies. The result is both drama and vérité: a reconstruction faithful to names, places and memories, deliberately avoiding the clichés of a horror film and cinematic in its restraint.

Ten years on, Paris remains altered but unbroken. As commemorative ceremonies are held all over the city and in France, the threat level remains extremely high. The lone surviving attacker, Salah Abdeslam, is serving a life sentence in a high-security prison.

Yet Des Vivants restores something the headlines could not: the individual, complicated human stories and torment of those who lived. Seen by millions of viewers since its France 2 debut, the series has touched a national nerve even if it is at times extremely painful to watch.

From the outset, Des Vivants was a project of listening. With co-writer Antoine Lacomblez, de Lestrade spent months interviewing the seven survivors twice, in June and again in October 2023. They spoke freely, sometimes hesitantly, and even with humour. But the director and writer said they had had to “stay close to their words, their silences”. “We couldn’t invent or condense. We had to write with their guts, not our cleverness.”

The story they shaped traces a decade in the survivors’ lives: from the terror of that night minute by minute although not in chronological order, and the surreal morning after. There are flashbacks, panic attacks, recurring nightmares, therapy sessions, compensation interviews — when some face cynicism and disbelief from officials who think they might be imposters who weren’t even at the Bataclan — to the first anniversaries and the long criminal and civil trials that brought a measure of justice. “The day after is often harder than the night itself,” de Lestrade said.

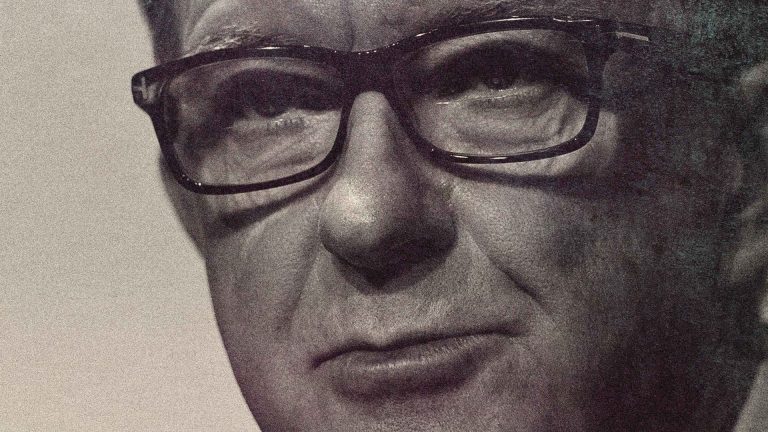

The survivors whose stories inspired the series have spoken publicly about what it means to see their experiences transformed into fiction. David Fritz-Goeppinger, one of the hostages and author of the memoir Il fallait vivre (We Must Live) described watching himself portrayed on screen as an accurate representation of the aftermath of terrorism and how it acts as “a kind of distorted mirror.”

“It seeps into the tiny, disgusting things that come afterwards — the breakdown of relationships, of work, of desire — and the series shows that extremely well,” he said.

For him, Des Vivants marks “a new stage” in how the tragedy is understood: “After the documentaries and the books, this one shows what really happened in our homes afterwards.”

Suggested Reading

Review: Society of the Snow is worth the nightmares

Sandrine Larremendy, the psychologist who worked on the production, sees fiction as part of the recovery process. “For victims, it allows a certain distance — a way to look at their story from another angle. For the public, it shows what living with trauma really means.”

Between 21:59 and 00:18 that night, the 11 hostages — strangers united by their love of the American rock band Eagles of Death Metal — were held at gunpoint by Foued Mohamed-Aggad and Ismaël Mostefaï, both armed with Kalashnikovs and explosives, as they heard the screams of the maimed and of those being murdered beyond the door and windows. The terrorists spoke, sometimes almost calmly, sometimes incoherently.

“It’s an extraordinary testimony of what happened in that corridor,” said Lestrade. “They are the only people who spoke with the terrorists during that night of horror and massacre.”

When the French BRI counter-terrorism unit stormed the hall, one attacker detonated his suicide vest. Miraculously, all 11 hostages survived. Episode 7 reconstructs that moment with chilling precision — the tense phone negotiations through a victim’s mobile, the deafening blast, and the sudden appearance of the heavily armed SWAT team who freed them.

Among the most terrifying real moments recreated in Des Vivants is that of Sébastien, one of the hostages who risked his life to save a pregnant woman dangling from a window two floors above the alley behind the Bataclan. The scene was one of the few captured in real time that night — filmed by a journalist from across the street — and her desperate voice crying, “I can’t hold on, I’m pregnant!” became one of the defining sounds of the attacks.

In the series, which incorporates fragments of real footage, the woman Sébastien saved reappears holding her baby girl — a moment of grace that restores fragile meaning to lives torn apart.

In another episode, the survivors even meet the BRI officers who rescued them, to ask them questions and to thank them, in another moment drawn directly from life — unprecedented in its realism, as the elite counter-terrorism forces usually remain faceless and anonymous.

For months after the attacks, the survivors lived with sometimes paralysing fear. The final member of the commando, Salah Abdeslam, escaped and disappeared; his long manhunt through Belgium kept many in a state of terror.

Every siren or breaking-news alert brought panic. When another jihadist attack struck Nice in July 2016, it reopened wounds that were still raw. Every new attack throws them back into the corridor, and they live again that unbearable night.

The decision to shoot scenes inside the real Bataclan provoked fierce debate. For many, the concert hall remains a memorial, a sacred space, not a film set.

Several victims’ associations and survivor groups objected. Arthur Dénouveaux, president of Life for Paris, said some found it “indecent to reconstruct the scene of the tragedy where they suffered and where their loved ones died.”

De Lestrade understood the hesitation but felt returning to the site was essential. “Are we allowed to have actors play hostages there? Is it obscene?” he asked himself. “But the Bataclan is part of their story — a moral obligation to show it as it is now, both a place of death and of life.”

Supported by a letter co-signed by the Potages, the production sought permission from the hall’s management to film a few key sequences. The answer, after long deliberation, was yes — under strict conditions.

The team filmed at night, in silence, with a minimal crew. “Being there was overwhelming,” said the director. “You could feel the weight of everything that happened.”

Filmed on Boulevard Voltaire, in the Passage Amelot, at the Palais de Justice courtroom where the trial was held, and at the Panthéon, Des Vivants advances without melodrama, or crass manipulation of emotion. Even the terrorists appear, with real faces and voices but without myth or justification.

Around the seven friends orbit their partners, parents, children, therapists, and the elite counter-terrorism officers who rescued them — as well as a character who befriends a survivor of the 2017 London Bridge terror attack, French woman Christine Ducros, and forms a romantic partnership with her, linking two cities scarred by jihadist violence.

Feelgood this series is not – despite the poignant scenes of sociability and pleasure as the friends try to enjoy, and both forget and remember together, in bars and restaurants, around music singalongs to Daft Punk’s Get

Lucky and at weddings. It is a fine line, but De Lestrade rejects what he calls the tyranny of “these catch-all words of resilience and recovery.”

He says: “We are saturated with stories that turn suffering into heroic epics, and we convince ourselves that we already know everything about these highly positive journeys. I would very much like Des Vivants to surprise us along this over-trodden path of “recovery”