One of the enduring rewards of human existence is that, sometimes, we get to sit somewhere quiet and read a novel. I am far from the first to observe that a good novel reveals more about the human condition than any philosophical or scientific theory ever could, and so far this summer, two books have stood out to me in that regard.

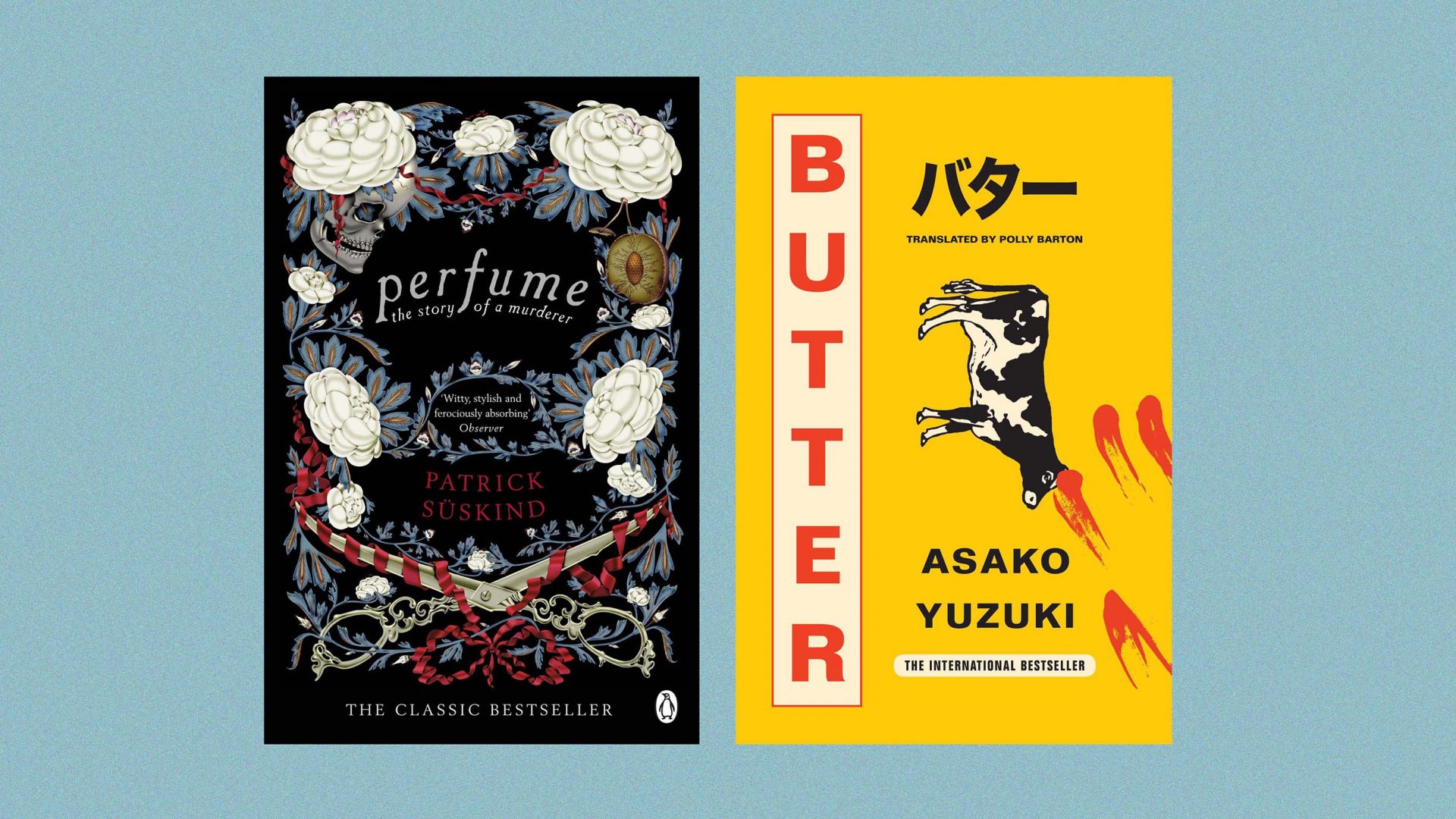

Patrick Süskind’s classic Perfume and Asako Yuzuki’s more recent Butter are both remarkable in their own ways, but even more remarkable is how well they complement each other, like fine wine and cheese. Both tell stories of murder, and both revolve around intense sensory experiences, specifically smell and taste.

Reading Süskind’s meticulous and immersive descriptions of the scents and stenches of 18th-century France alongside Yuzuki’s sumptuous accounts of the pleasures of buttery food, made me realise how rarely these senses receive such careful attention, and how little time we spend thinking about them in our day-to-day life.

In fact, a recent study found that a majority of young people would rather lose their sense of smell than give up their phone or laptop. This appears to confirm what many of us intuitively believe: smell is the least important of our five senses, far behind sight and hearing. In our hierarchy of senses, taste ranks slightly higher, but only because of the common misconception that it exists on its own. In fact, most of what we perceive as taste is actually driven by smell. Clearly, these are not matters that we take very seriously.

Just ask Dr Ally Louks, who in November 2024 posted a photo of herself holding the PhD dissertation she had just successfully defended, titled “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose”. What should have been a quiet celebration in a niche corner of academic Twitter instead sparked a wave of online abuse.

Trolls were upset that a woman dared to celebrate her intellectual achievement, especially for what they deemed such a “useless” topic. Beneath their rampant misogyny and blind rejection of anything affiliated with the nebulous category of “woke”, lay another, by contrast more innocuous, belief: smell is not worthy of scholarly attention.

This way of thinking is nothing new; in fact, it has permeated western thought for over two millennia. The language of western philosophy carries a strong visual bias, one that led French philosopher Theodor Adorno to call it a “peephole metaphysics”. After all, we talk about ideas as “views” and not as odours.

Suggested Reading

Au revoir les philosophes

From Plato to Kant and beyond, sight and hearing have been represented as the “higher” senses because they are considered more objective. By contrast, the “lower” senses of touch, taste and smell, are believed to be bound up with our most primal appetites and animalistic tendencies. Philosophers have dismissed them as morally suspect, likely to tempt us into lust and gluttony, and as distractions from the most important human activity (according to philosophers): speculating about abstract ideas.

There is an undeniable murkiness to taste and smell: they can vary dramatically depending, for example, on whether a person is pregnant, or whether we can see the source of the smell or taste. They are also known to carry strong evocative powers (most famously explored by Proust) and they don’t even need to be at the forefront of our awareness to affect us and guide subconscious decisions.

But this murkiness should not be an excuse to dismiss the “lower” senses as unworthy of investigation, nor to discount what taste and smell might reveal about ourselves.

In both Perfume and Butter, smell and taste are markers of identity and self-discovery. The sociopathic protagonist of Perfume, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, is born with a sense of smell so extraordinary he can find his way in the dark through a kind of olfactory echolocation. But he discovers with horror that he has no scent of his own, triggering an existential crisis.

In Grenouille’s world, scent is synonymous with individuality and even personhood: “there was a basic perfumatory theme to the odour of humanity… a sweaty-oily, sour-cheesy, quite richly repulsive basic theme that clung to all humans equally and above which each individual’s aura hovered only as a small cloud of more refined particularity”. It is precisely because Grenouille lacks this aura that he is both perceived, and comes to perceive himself, as inhuman.

Butter follows Rika Machida, a journalist stifled by the impossible, misogynistic demands of modern Japanese society. Encouraged by a female serial killer awaiting trial whom she is trying to interview, Rika abandons her merely functional approach to food for a truly indulgent one.

She experiences the introduction of real butter to her ordinarily plain rice as a “shining golden wave, with an astounding depth of flavour and a faint yet full and rounded aroma [wrapping] itself around the rice and [washing her] body far away”. This simple act of eating for pleasure helps her break away from the cultural constraints and suppressed desires that have long bound her. By embracing the pleasures of flavour, she is able to approach a version of herself that exists outside society’s expectations, a more liberated and authentic self.

These fictional, and in the case of Perfume fantastical, stories reveal that taste and smell are far more than the vestiges of our animal past, and that they deserve greater attention. The few philosophers who have taken these senses seriously have observed that smell and taste can teach us a lot about how our minds work.

One such thinker, philosopher and cognitive scientist Ann-Sophie Barwich, explores this in her fascinating book Smellosophy: What the Nose Tells the Mind. She discusses how smell, and by extension, taste, challenges traditional philosophical views on the relationship between mind and world. She retraces the comparatively short history of the olfactory sciences and demonstrates the potential of studying perception from an olfactory perspective to deepen our understanding of the brain.

Works like hers are only now beginning to rectify centuries of neglect of taste and smell in scholarly research. Thankfully, some great novels have been doing much of the heavy lifting in the meantime.

Emily Herring is a freelance writer and editor