When I look at who currently rules the world, all I see are men with overinflated yet tragically fragile egos. These narcissistic types don’t have a self-deprecating bone in their body. Have you ever heard Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump express humility in any form? It’s quite the opposite. Their vanity goes so outrageously unchecked that it routinely spirals into the grotesque, the risible, the downright comical.

Think about the countless photos of Putin, shirtless on horseback. Or scroll through Trump’s tweets and you’ll find gems like this one from 2013 (a simpler time): “Sorry losers and haters, but my I.Q. is one of the highest – and you all know it! Please don’t feel so stupid or insecure, it’s not your fault.”

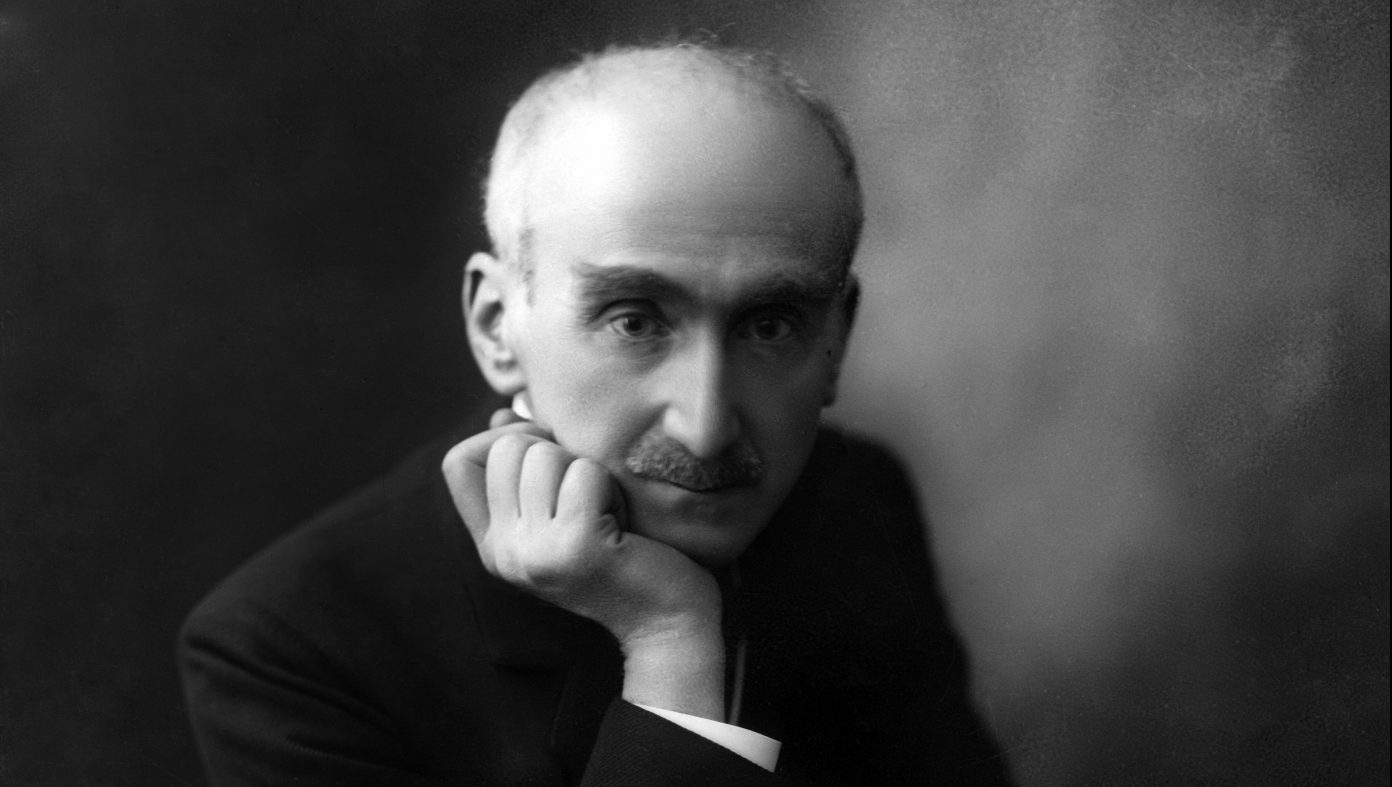

The tweet is undeniably funny, though in a laughing-at, not laughing-with way. And if these men weren’t in charge of large nuclear arsenals, their vanity would be funny. But why does vanity make us laugh? The French philosopher Henri Bergson may provide an answer.

In 1900, Bergson, until then best known for his profound theories of time, free will, and memory, turned to laughter, which most philosophers had dismissed as trivial. Laughter: an Essay on the Meaning of the Comic is far from a funny read, but only because he treated his subject with the utmost respect. He approached it not as a dry concept to be dissected into even drier abstractions, but as a living phenomenon to be observed as it manifests in its natural habitat: human society.

Rather than offering a strict definition of the comical, Bergson identified a leitmotif, a common thread running through various forms of comedy: we tend to laugh at “something mechanical encrusted on the living”. A man slipping on a banana peel is funny, in this regard, because “where one would expect to find the wideawake adaptability and the living pliableness of a human being”, we instead encounter “a certain mechanical inelasticity”.

That same inelasticity, Bergson argues, shows up not only in slapstick, but in human character. Just as inattentiveness to our surroundings can cause (often comical) physical mishaps, an inflated sense of self prevents us from paying attention to others, which can, in turn, harm society.

This harm is subtle and, Bergson writes, therefore requires a subtle antidote: “We should see that vanity, though it is a natural product of social life, is an inconvenience to society, just as certain slight poisons, continually secreted by the human organism, would destroy it in the long run if they were not neutralised by other secretions. Laughter is unceasingly doing work of this kind. In this respect, it might be said that the specific remedy for vanity is laughter, and that the one failing that is essentially laughable is vanity.”

Suggested Reading

When Epicurus took an all-inclusive holiday

When Trump tweets: “I went from VERY successful businessman, to top T.V. Star … to President of the United States (on my first try). I think that would qualify as not smart, but genius…and a very stable genius at that!” he exemplifies the kind of maladapted, self-absorbed (and thus inattentive) attitude that laughter gently, but effectively, seeks to correct.

Narcissists are therefore terrified of laughter and have devised various ways of suppressing it: through delusion, like JD Vance pretending he was in on the joke when a recent South Park episode made a fool of him; through threats, like Trump hinting at cancelling late-night show comedians; through censorship, like Elon Musk banning people who mock him from the platform he bought for billions; and in harsher regimes through imprisonment and violence.

The narcissists who govern us try to distract from how grotesque they really are. We are told to blame our problems on immigrants one week, trans people the next. So much of news, political discourse, and social media algorithms are designed to keep us in a state of anger or fear.

According to Bergson, “laughter has no greater foe than emotion.” When the emotional stakes are too high, they prevent the “momentary anaesthesia of the heart” that laughter requires. This is of course not to say that it’s impossible to laugh in times of hardship. On his death bed, Voltaire allegedly told a priest who was exhorting him to renounce Satan: “This is no time for making new enemies.” Much humour arises from dark places, no doubt because there is catharsis in the emotional detachment it demands.

Laughter also allows us to highlight oppressive structures in a language that everyone can understand. It helps us to pick apart the mechanics of our world that are too rigid, regain control over the stories being told, and point out the parts that need to change.

The endless memes on Twitter distorting Vance’s face, so thoroughly that many people have forgotten what he actually looks like, may not seem like much against the US administration’s drift into authoritarianism. But these posts are a heartening reminder of a shared defiance. They draw people together in a catharsis of silliness and point at something very wrong.

Our world is desperately lacking the “delicate adjustment of wills” and “reciprocal adaptability” that Bergson argued were essential for maintaining a healthy society. When we get sucked into endless outrage cycles, we are distracted from our greater calling: uniting in collective mockery of the most antisocial beings among us, narcissistic, power-hungry billionaires and their friends. It might not be enough to solve all the world’s problems, but it should help us remain sane.

Emily Herring is a freelance writer and editor, whose book Herald of a Restless World is the first biography of Henri Bergson in English