I recently got to see two very different but equally life-changing concerts. First, I saw Beyoncé, an artist I do not hesitate to call our greatest living entertainer, take over Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in London, one of the stops on her Cowboy Carter tour. At 43, the Houston-born singer sits atop a career spanning nearly three decades, has amassed more Grammy awards than anyone else in history and has cemented herself as one of the most influential figures in 21st-century culture. I watched as thousands of fringed jackets and bedazzled cowboy hats filled the stadium and let the almost three-hour show wash over me like a glitter-spurred vitamin shot.

Second, I saw the Yeah Yeah Yeahs in a more intimate venue: Manchester’s O2 Apollo. The New York trio were celebrating their 25th anniversary with an introspective set featuring acoustic and string arrangements of some of the deeper cuts from their repertoire. In the early 2000s, they rose to the forefront of the indie boom alongside bands like The White Stripes and The Strokes and stood out with their explosive energy and raucous glamour.

Since then, they have become one of the most singular, exciting and enduring voices in alternative rock. My heart surged at the idea of seeing my idol, lead singer and all-round icon Karen O, who has a range that allows her to float effortlessly between electric rawness, chaotic joy, and devastating softness. That night, the latter two took centre stage. Another vitamin shot for my soul.

The singers inhabit two different realms of celebrity: Beyoncé is a global superstar revered as a kind of goddess, while Karen O has a more niche but no less passionate following. Yet both hold an equally important place in my millennial heart.

Beyoncé launched her post-Destiny’s Child solo career in 2003, the same year the Yeah Yeah Yeahs burst on to the international scene with their debut album Fever to Tell. Funnily enough, one of the album’s most beloved tracks, Maps, a tender outlier on an otherwise feral and sexually charged record, was interpolated over a decade later on Beyoncé’s critically acclaimed 2016 album Lemonade, earning the band writing credits. 2003 was also the year before I entered my teens, and I was already beginning to face the realities of womanhood in the early 21st century.

The past few years have seen a trend of Y2K nostalgia mainly driven by those too young to have experienced the turn of the millennium. While I wouldn’t trade the social media-free years of my early adolescence for whatever Gen Z and Gen Alpha are going through today, I wouldn’t say that the early 2000s were an especially great time to be hitting puberty either.

Looking back, all I see is a nonstop spectacle of women being humiliated for sport. Fresh off the “heroin chic” trend, anything other than a size zero was deemed unacceptable, and women, including Beyoncé, were routinely shamed in tabloids for the crime of having cellulite or round hips.

Then there’s what they did to Britney Spears, endlessly sexualised as a teenager, then remorselessly vilified and ridiculed until she broke completely.

There was also Eminem gleefully rapping about violent fantasies of murdering his ex-wife, the casual use of “gay” as an insult, and the way trans women were the butt of inconceivably cruel jokes in the mainstream media (though of course, we still have a long way to go on that front).

By the time I hit my teens, I had internalised a slew of confusing and contradictory expectations about how I should behave and present myself to avoid being shamed. I couldn’t be perceived as too prudish, but I felt it would be equally wrong to express any interest or curiosity about sex. I couldn’t be seen to care too much about my looks, but I could never let anyone catch even a glimpse of leg or armpit hair. In short, I was experiencing what has come to be known as the internalised male gaze.

Suggested Reading

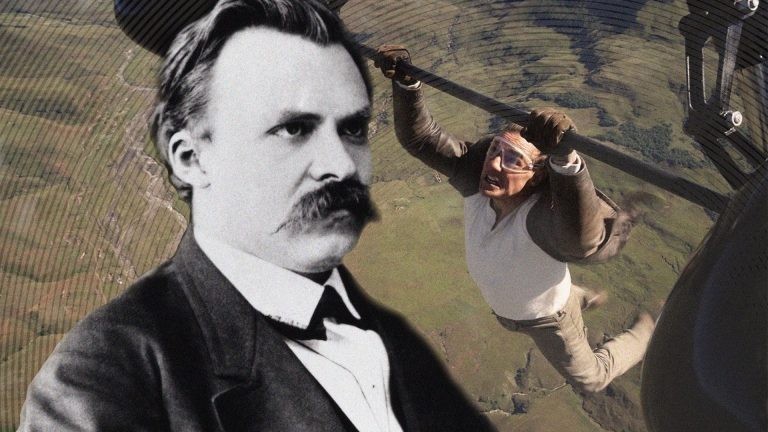

Tom Cruise, the Nietzschean Superman

The concept of the male gaze was first popularised by film theorist Laura Mulvey in 1975 and was most succinctly summarised by the art critic and novelist John Berger: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” The idea is that our films, art and literature reflect a patriarchal narrative of women as passive objects of straight male desire. In turn, women often end up focusing this lens of objectification inward, skewing their own relationship with themselves.

In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir described how self-alienating the internalisation of an external male gaze can be in a woman’s development: “The little girl feels that her body is escaping her, that it is no longer the clear expression of her individuality; it becomes foreign to her; and at the same moment, she is grasped by others as a thing: on the street, eyes follow her, her body is subject to comments; she would like to become invisible; she is afraid of becoming flesh and afraid to show her flesh.”

Without having the words to express it at the time, this is exactly how my adolescent self felt. That changed when I saw a video of Karen O in a dragon-green leotard, her hair in a bowl cut that no one else on the planet could pull off, eyes decorated with wild war paint, screaming and writhing on the floor at the 2006 Reading Festival. Never had I seen a woman be so overtly sexual (“I like to sleep with him, pushing in the pin” she screeched) yet completely unconcerned about how she was being perceived. That day, at 15, I learned that female sexuality could be loud, self-centred, ugly, and joyful, and that it was possible for a woman to achieve total abandon even under the gaze of thousands.

Beyoncé on the other hand, at a superficial glance, appears to conform more readily to the traditional trappings of the male gaze. By any measure, she is what we call sexy, and this is an image she has always actively cultivated. Like any mainstream female music star, and especially as a Black woman, she has faced intense scrutiny within a somewhat tired debate: does her performance of sensuality reinforce the male gaze or reclaim it? Can women be sexy and still be good feminists?

But in many ways, these questions are simply too narrow to hold the complexity of her vision. In the intricate visuals of her music videos and live performances, especially over the past decade, she invites us to see beyond the simplistic binary of gazer and gazed-upon. During one of the interludes of the Cowboy Carter show, the stadium screens light up with a video of her performing an old timey, coin operated, cowgirl-themed peep show for an entranced cowboy, who is none other than herself. The male gaze is not just subverted, it is pulverised. Here, as in so many of her works, Beyoncé’s sexiness is fully embodied, never passively displayed, always presented as the expression of a fully realised artist and performer. In short, Beyoncé remains sexy whether or not men are watching.

As she has matured, one of Beyoncé’s goals has been to expand our gaze. Her more overtly sexual songs centre women not as objects of desire, but as active desiring subjects.

She seamlessly melds Black history, the present-day political challenges, her personal life and a constant unapologetic refrain of self-celebration. Just as she always knows her exact angle with every camera on stage, Beyoncé performs and presents herself in a way that acknowledges the gaze directed at her, seizes it and redirects it towards a broader, more complex picture. Through full control of her image and her visual lexicon, she too achieves total, joyful abandon in her performance.

Two years ago, at a festival in London, I watched Karen O provocatively push her microphone into her mouth. Then she shoved it down her leggings creating a mock erection, before smashing it on the ground like one of Jimi Hendrix’s guitars. Finally, she tossed it into the crowd and by some miracle granted by the rock gods, it landed in my partner’s hand, then in mine.

I’ve kept it as one of my most prized possessions, a reminder that I owe it to my teenage self to not give in to anyone else’s expectations.

Beyoncé’s current project is a three-act affair that explores, celebrates and expands upon the Black roots of music genres, like dance and country, that have long been co-opted and dominated by white performers. If, as rumour has it, Act III turns out to be a rock album, she should definitely give Karen O a call. Though honestly, I don’t know if this millennial’s heart could survive such a powerful collaboration.

Emily Herring is a freelance writer and editor