Every country has its stereotypes. Britain? Fish and chips and red buses. Germany? Great beer and cars. South Africa? Sunshine and racism. It’s an uncomfortable joke. Maybe not a joke at all. It’s also true.

Even 30-odd years into democracy, apartheid and its consequences linger in the background of South African life. Our experience with racism isn’t just something that happened in the past; it’s a core characteristic associated with my country.

As the comedian Loyiso Gola has joked, our racism is world-class. While other cultures are subtle about it, we were so good at being racist it became our defining characteristic.

There’s a deeper truth behind this that’s often overlooked. Historical racism in South Africa was very successful. It wasn’t something that happened by accident. A system was created that did exactly what it set out to do. Apartheid was engineered to separate people into groups and to treat one group better than the other. It was hierarchical and prejudicial in its nature, and it built a highly functional system. What a strange idea it would be to expect a carefully trained monster to die and leave no ghosts.

Those ghosts are alive in South African life. Systemic racism continues in economic disparity, in the apartheid-era land divisions that persist, and in outright discrimination – and all of this happens in a country that is around 80% Black.

Worst of all, I see those ghosts in my own subconscious. I might consider myself a committed anti-racist, but the legacy of growing up in such a deeply divided country lives on. Without realising it, I immediately clock the race of everyone when I walk into a room. If a group of black men walk towards me on a street, I am far more likely to make assumptions or want to cross to the other side.

I think of father Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest from New Zealand, who lost his hand and eye to a letter bomb during the anti-apartheid struggle. “The day I arrived in South Africa, I stopped being a human being and I became a white man,” he said. It makes me wonder if the legacy of my country taught me to always think of myself as a white woman first?

These ghosts of the apartheid monster aren’t just hidden in my philosophical musings. They’re alive in the headlines, especially now that an inquest into a defining apartheid era crime has been reopened.

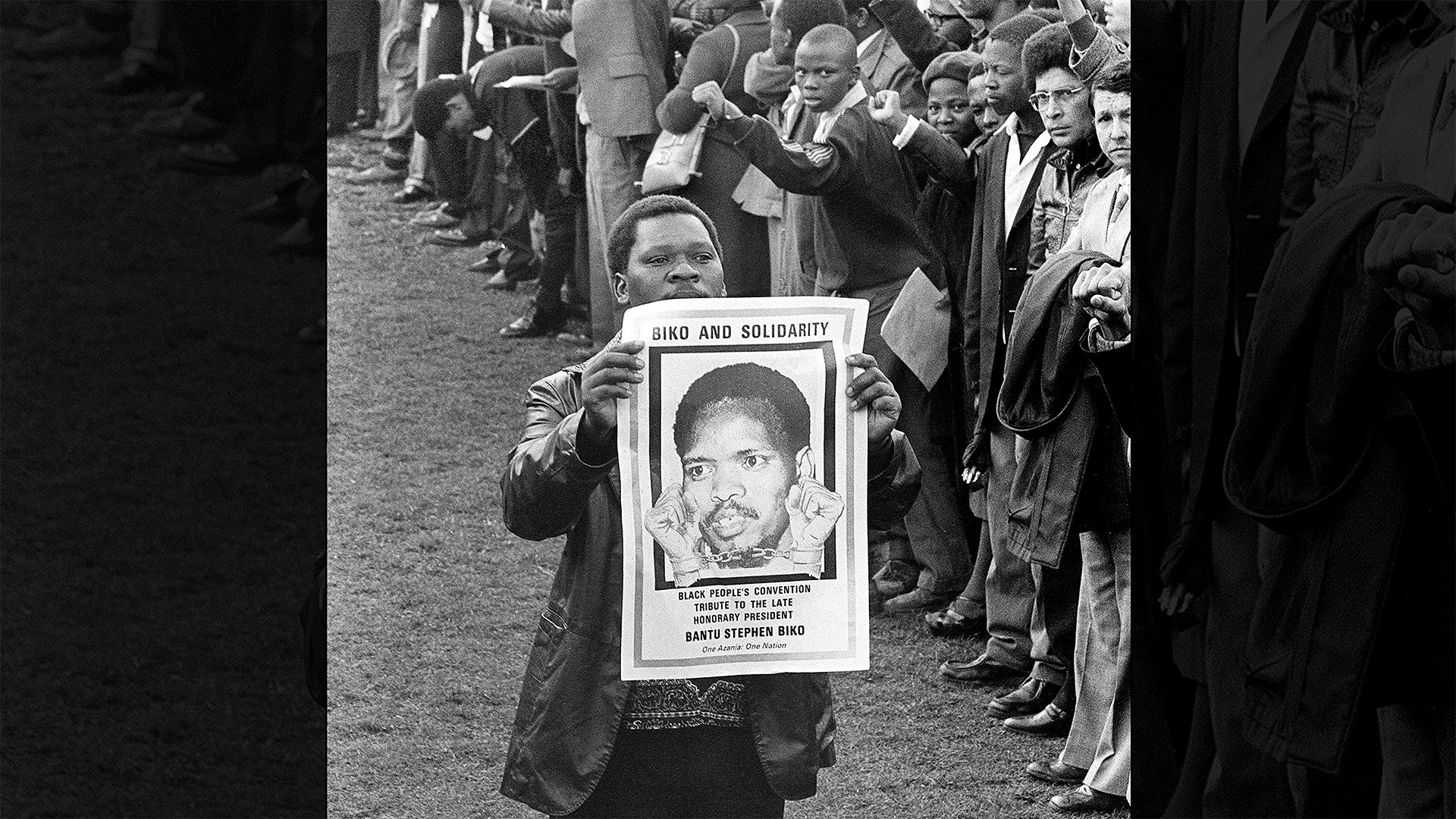

The anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko died 48 years ago in police custody, after days of brutal interrogation. Denzel Washington portrayed Biko in Cry Freedom, in a performance that conveyed his larger-than-life force. Biko’s death cut deep for many South Africans.

But, watching the movie again now, it’s not Biko’s charm and conviction that strikes me. Rather, it’s that the film, in a way, glosses over the climactic moment of his death. That is not just a creative choice to cover up the killing. It is also a hint at the mystery surrounding those events.

An initial inquest, followed by the years-long Truth and Reconciliation Commission, didn’t hold anyone to account for what happened to Biko. Now, a new inquiry has been set up, even though several critical witnesses have since died. It is part of a larger move in the country to follow up on cases that should have been prosecuted decades ago.

This delay in justice reflects wider problems with the way in which crimes have been handled, both then and now. Corruption and political interference have meant that many apartheid-era crimes and traumas have not been addressed. It also means that families have gaping holes in their lives, with shared traumas that cannot be addressed.

I accept the stereotype of South Africa as a country reborn from racism. Not the tired rainbow nation narrative that children of the 90s like me got told in their cribs. But rather in the sense of accepting scars as what they are. Working through them, rather than around them.

Suggested Reading

South Africa’s winter is here

There is still racism in South Africa. It’s systemic, it’s classist, sometimes it’s spontaneous and aimed at groups that weren’t even fully on the radar before, like the ongoing xenophobia against black Africans from other countries.

But the most important question isn’t whether there is a legacy of racism. There obviously is. Much more important is what to do about it. My answer? Don’t ignore or minimise it. Let it be obvious. Let it air. And, for goodness’ sake, try not to make things even worse by bungling the processes that are meant to lead towards some kind of resolution.

In other words, the ghost of the monster must speak, so that it can be heard out. I couldn’t care less about another commission, or a half-hearted day of remembrance. I’m speaking of giving those who suffer what they need. That’s the only way ghosts truly die.

Elna Schütz is a Johannesburg-based journalist working in audio and writing