The Louvre sits at the centre of Paris, which is the political and cultural centre of France and once upon a time was the power centre of the world. And at the centre of the Louvre is a 69-foot-tall, 200-ton glass-and-metal faux Egyptian structure designed by the Chinese American architect IM Pei.

Reviled and ridiculed by critics as a foreign object created by a foreigner when it opened in 1989, it is now celebrated as a vision of France’s modernity.

The Pyramid adorns the Louvre like a diamond from outer space that landed smack in the middle of the Cour Napoléon, the sweeping open space embraced by the museum’s wings. The Pyramid attracts so much attention that visitors sometimes overlook that there is not just one pyramid; there are five: three miniature versions are in the courtyard itself, and an inverted version serves as both a skylight and a piece of sculpture in the Carrousel du Louvre, the underground shopping mall that was another part of Pei’s plan.

Impractical though it may be, the Pyramid inspires and fascinates. In the words of one of its most passionate champions, the former New York Times art critic John Russell, “The glass is thin, the struts and supports look like the ankles of a gazelle, and the action of the light on and through the slanting panes of clear glass is never the same for two seconds together.”

Philippe Carreau, the Louvre’s chief architect, has studied the Pyramid’s light for years. “In the mornings, when the sun lights up the small droplets of dew, it looks like a giant spiderweb,” he said.

During the day, its glass panes mirror puffy clouds, and one sees the colour of the sky move from bright white to gunmetal. When winter descends on Paris, the Pyramid can stay a stubborn cold metallic grey for months.

When the summer sun is determined to linger into night, the Pyramid’s metal frame shines and sparkles, throwing shadows on to the stones of the pavement. Then the sun shines on the Pyramid from the west, and the facade changes colour as the sun goes down. When the sunset is strong enough, it turns the metal frame a reddish colour. At night, artificial lights bathe the Pyramid both inside and out.

“The Pyramid is happiest at night,” Carreau said. “I started to see this phenomenon of light from the moment the Pyramid was built. I was very, very moved then, and I am still very, very moved. You rarely experience such a thing.”

I call Carreau “Mr Pyramid” because he is responsible for maintaining, cleaning, lighting, and polishing the structure. He also holds the keys to the Louvre’s locks, supervises the evacuations of artworks when the basements flood, oversees repairs to roofs and masonry, and monitors the plumbing and electrical systems. The Pyramid is the most thrilling part of his job.

Carreau exudes cool in the buttoned-up Louvre. His high brush cut is flecked with grey. His eyeglass frames are bronze with brown polka dots. He wears corduroy sport coats with sober thin ties and black trousers even when he is investigating a problem with the Pyramid’s lighting or climbing up scaffolding. His brown oxfords are worn and scuffed. The ringtone on his phone is the sound of violins.

From inside the Pyramid, Carreau showed me how the structure was built to maximise transparency. “If you look closely, you can see that there are very few thick supporting bars,” he said. “Instead, there are many thin connecting tie-rods – as many as possible. They form an architecture very pure, very fine, very light, a bit magical, that makes you wonder how it stays put.”

IM Pei was obsessed by lighting, Carreau said, pointing out spotlights in the walls and ceiling. Pei insisted on total transparency in the Pyramid’s 118 glass triangles and 675 rhombus shapes, known as lozenges. “The presence of light during the day extends until night,” Carreau told me. “The result is quite soft. It gives the Pyramid a futuristic feeling.” He described the Pyramid’s glass as “extra white, the most transparent glass possible.”

The French manufacturing company Saint-Gobain took two years to perfect the process of manufacturing what it calls “diamond glass.”

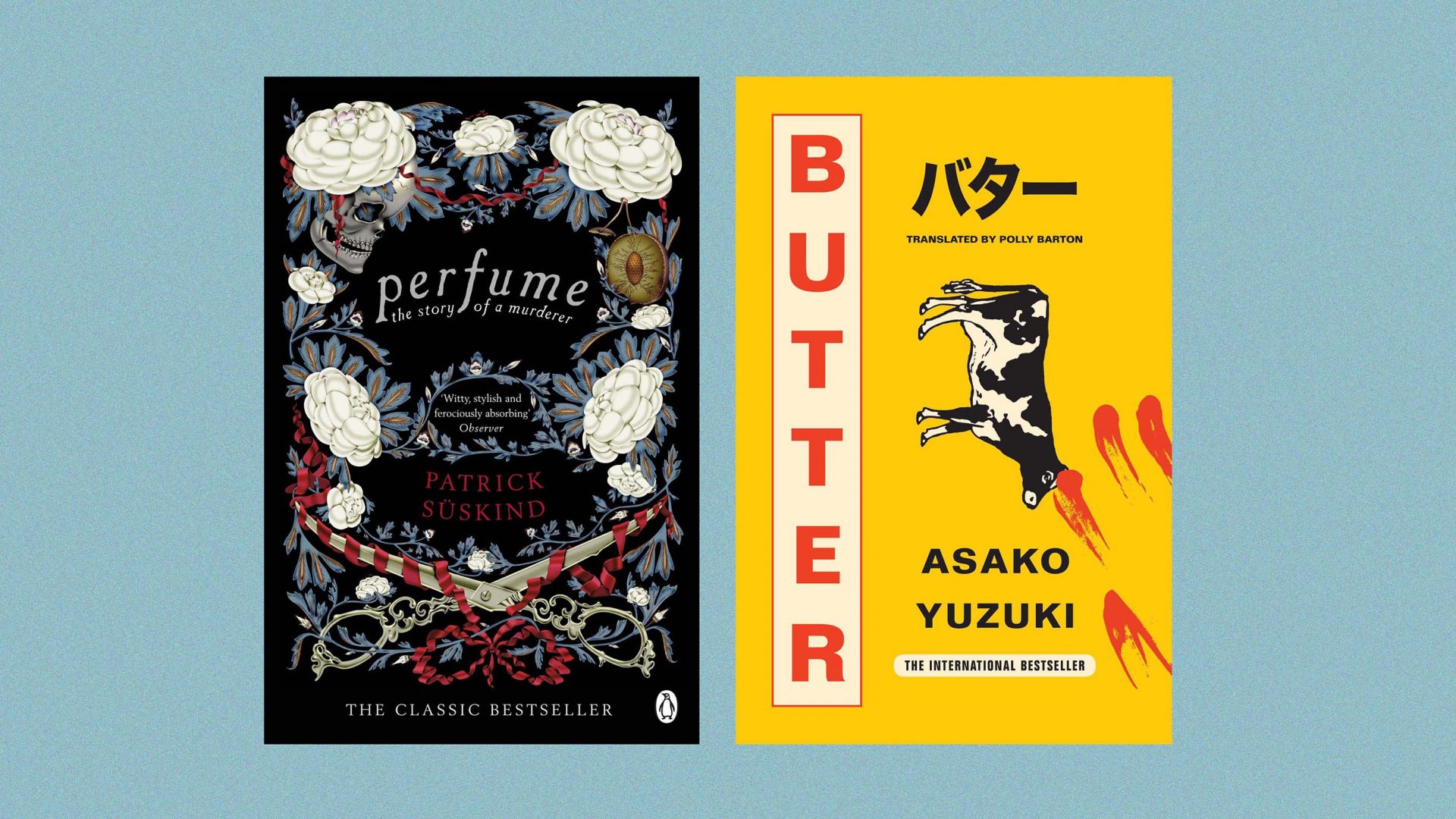

Suggested Reading

The rebirth of Notre Dame

It built a special furnace capable of removing the iron oxides that tint and distort. On opening day, when misty clouds shut out the sun, Pei was delighted to see the clarity of his glass. “The Pyramid is even more transparent on a grey day when it takes on the moodiness of the Paris sky,” he said.

Cleaning the Pyramid just might be the most difficult window-washing job in Paris. Carreau recognised the problem early on. In 1987, when he started out as a young intern at the museum, he chose “How to clean the Pyramid” as his project. On the inside are hard-to-reach crevices. Outside, the panes must be washed at least once a month, more often in summer, when dust and sand kick up and stick like glue to the hot glass.

In the early years, the Louvre hired professional mountain climbers to help. But ropes, scaffolding, or a carriage system dropped from above didn’t work. Robots saved the day, helped by human window washers who mount small remote-controlled cabins inside the Pyramid to get into the corners.

I saw the outside cleaning ritual up close one day when a nondescript white truck drove onto the Cour Napoléon and plugged into the Louvre’s main water system. Didier Lacloche and Laurent Hirigoyen, technicians who work for a private company contracted by the Louvre, unrolled hoses from the inside of the truck, started the engines of machines that supplied electricity and distilled water, and pulled out the robot.

“The pressure’s on, of course, and I have to stay focused,” said Hirigoyen. It was his first time as the head of the cleaning brigade. “This is a very technical robot, and with one wrong move there’s danger.”

The 80kg Swiss-made robot, created in 2019 and named Gekko, is a motorised pioneer in window washing. It replaces an earlier version that was too weak to mount the 50-degree slope of the Pyramid’s walls and frequently broke down. Gekko functions with small blue suction cups arranged in two rings, one for rotation and the other for movement back and forth. The cups move like centipede legs. The robot has a long white rolling brush connected to a yellow cable and a long rubber apparatus that looks like a giant squeegee, hissing as it moves.

Lacloche moved the robot with control buttons on a large orange box strapped like an oversized bum bag above his hips. As it climbed the steep incline up the glass Pyramid, Gekko looked like a shiny Mars rover against the blue sky. It moved in unexpected ways: slithering like a snake, advancing rhythmically like a mechanical dancer, gliding straight ahead like a boat on a sea of glass. On their way into the museum, families with small children stopped to watch.

Lacloche and Hirigoyen agreed that their special time to visit the Louvre was in the quiet of Tuesdays, when the museum is closed. “It feels like I’m on a trip,” said Hirigoyen. “Art, it’s not really my field. How to put it – even if you don’t really know the sculptures and the paintings, you are carried away by the architecture itself, like you’re alone in the world, travelling through these huge rooms. It’s really this feeling of being very small, in an absolutely immense world.”

Lacloche agreed. “It’s special, when you’re alone in silence,” he said. “You need a lot of calm, you need silence, not many people around you. This is when you feel things. It might be a painting where you study the artist’s pencil lines and paint, and the characters and their expressions. Paintings are like a book.” Consciously or not, he echoed one of the most famous sayings about the Louvre, by Cézanne, who once referred to the museum as “the book from which we learn to read.”

By the end of the day, the Pyramid was washed and dried, its clear panes gleaming. The two men surveyed their work. “You feel as if there’s a spirit here, the past stones of the Louvre clashing with the modern glass of the Pyramid,” Hirigoyen said. “You’re taken in by the ambience, the phantoms of the past.”

“The Pyramid is the diamond of Paris,” Lacloche added. “It’s the jewel; it’s modernity. And we love this diamond. We made this beautiful diamond brilliant.” The day was grey, but sometimes, when the work is finished, when the Pyramid glass is sparkling clean and the sun shines bright at just the right angle, he sees rainbows.

He pulled out his iPhone and showed me close-up photos he had taken of tiny, brightly coloured rainbows streaking across the glass panes. “So very pretty,” he said. “I’m so lucky to work here.”

Later, Lacloche sent me an email with photos attached and the words: “I am sending you the rainbows of our beautiful diamond.”

Adventures in the Louvre: How to Fall in Love with the World’s Greatest Museum by Elaine Sciolino is published by WW Norton & Company