“When a writer dies before their work receives full recognition they are unable to shape and determine a desired audience… their work exists as a territory apart from all belonging, there for any reader, scholar to claim.” That was what black feminist writer bell hooks said about the performance artist, film-maker and poet Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, who was murdered by a security guard at the Puck Building in Manhattan in 1982 as she waited for her husband.

When she was killed, Cha was 31, and Dictée, the book that distilled her ideas – the poet Lucy Alford called it her “scrap-worked memoir” – had just been published. It became her masterwork and her memorial.

Just as hooks described, Dictée has travelled down the generations, each new wave of artists and scholars finding in it a reflection of their preoccupations. For experimental white poets in the 1980s, it was the book’s abstrusely original form that captivated them. For American-Asian artists in the 90s, it was the voice of a kindred spirit. For present-day students enrolled on critical race-theory courses, Dictée has become a multifaceted artefact of overlapping perspectives, ripe for decoding.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha was South Korean, born in 1951 in Busan six years after the second world war brought the Japanese occupation of her country to an end, leading to its partition between north and south. In 1962, Cha, with her parents and four siblings, left Korea, emigrating first to Hawaii, then to the Bay Area of San Francisco in 1964. These experiences had a profound effect: feelings of displacement and exile became regular themes, reflected in her see-sawing between three languages: Korean, English and French.

In San Francisco, she became an American citizen and studied at the University of California, Berkeley, where she took four undergraduate and graduate degrees in art and comparative literature, with a stint in Paris to study film and a short stay in Amsterdam.

This was a time of great upheaval on campus: student activism was exploding, with protests about civil rights, free speech, Vietnam and women’s rights. Underpinning it was a sense of community and a questioning of what a university education was for.

In the art department where she studied, product-orientated art destined for gallery walls was rejected in favour of the more experimental, process-led approach emerging in Conceptualism and Fluxus and expressed in film, installation and performance.

Suggested Reading

Diamonds, silk and the guillotine

In contrast to the fevered times, Cha’s work was measured, ordered and restrained. She used materials familiar to student life – notebooks, graph paper – and chose the black and white of a newspaper front page and the white of a Korean ritual robe as her aesthetic.

Her performances were “trance-like”. “We [were] floating, coming close to something, suspended, yet in a vortex of ineffable thoughts and sensations,” said the artist Judith Barry.

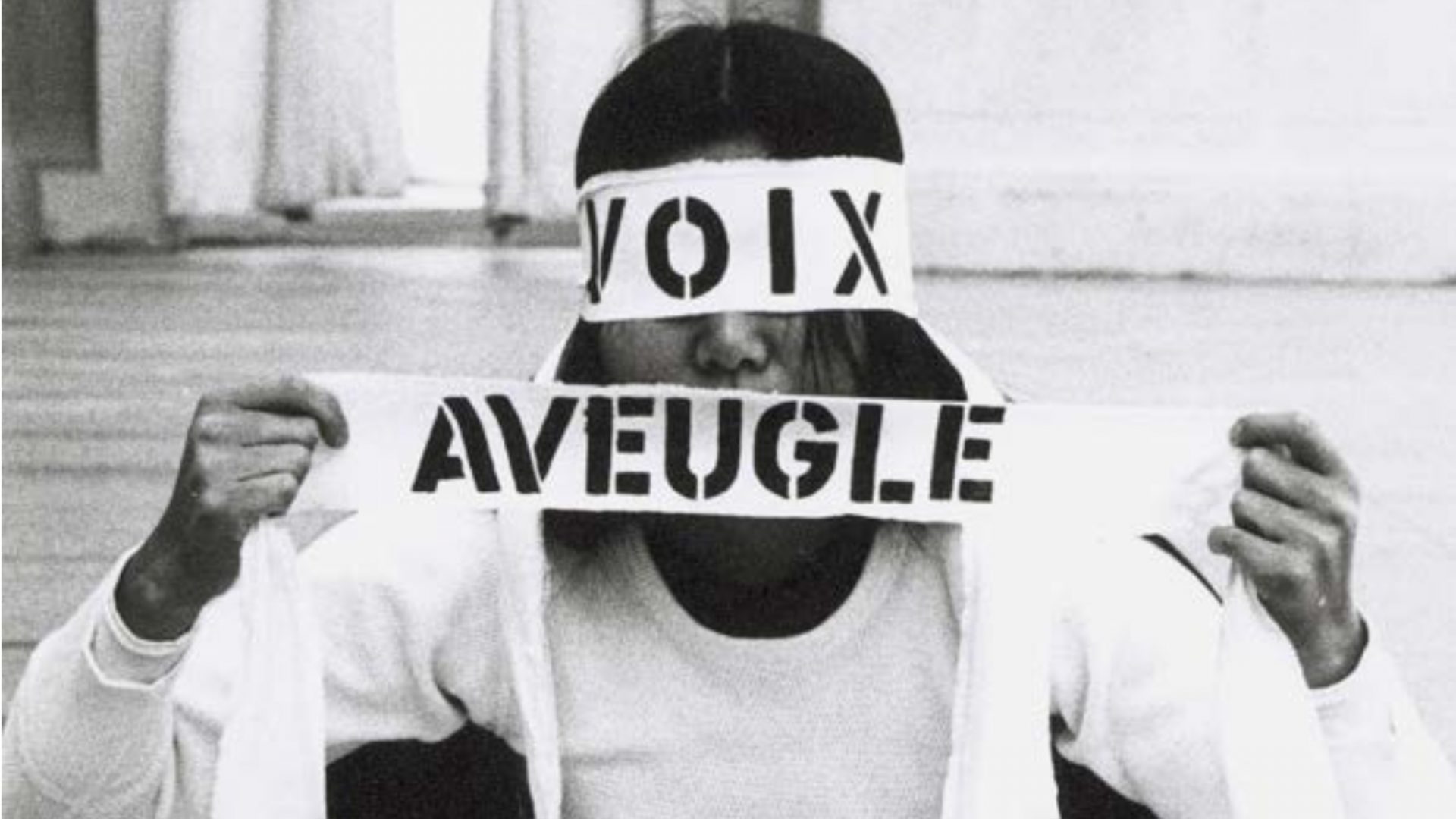

After finishing her studies, Cha continued with the idea that “language is a common denominator”. She photocopied pages of concrete poetry, tied together in handmade paper brushed with black ink calligraphy (Earth, 1973); newsprint collages and mail art, in which envelopes and postcards are rubber-stamped with elliptical phrases (Audience Distant Relative, 1972-78); performances (Aveugle Voix, 1975) and slide projections and films, such as Mouth to Mouth (1975) where Cha silently mouths the eight Korean vowel phonemes, intermittently obliterated by video static, a visual signalling of erasure and loss.

Often, Cha’s texts are broken up, words split and set down in different directions. “She loved taking words apart and putting them back together,” recalled her friend Yong Soon Min.

A new retrospective of Cha’s work, Multiple Offerings, opens in January at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (Bampfa), part of the University of California and custodian of the Cha Collection and Archives. The exhibition takes place in a similarly febrile moment, when the presence of ICE troops in California and, with tragic results, Minnesota, is ramping up the precarity of immigrant lives.

Book Works has brought out the timely distinguish the limit from the edge, which slides some of Cha’s unpublished writing into folded proximity with that of contemporary Guadeloupean artist Jimmy Robert.

When Cha was killed, she was planning White Dust from Mongolia, a 40-minute film and book-length text exploring memory, begun when she visited Korea after a 17-year absence. Memory was important for Cha. With this exhibition and publication, her memory is more alive than ever.

distinguish the limit from the edge by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha & Jimmy Robert is published by Book Works. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: Multiple Offerings is at Bampfa, Berkeley, January 24 to April 19

Deborah Nash studied visual art in Nanjing, China and Bourges, France