On entering Tate Modern’s much-anticipated retrospective of Emily Kam Kngwarray (c.1914-1996) you hear the artist singing with Maggie Kemarr and Polly Pwerle in a field recording from 1983. Their voices scrape the air, raucous and elemental, filling the gallery with the sounds of Alhalker Country (Sandover, in English, also known as Utopia), a remote region in Australia’s Northern Territory. The song is sung in Anmatyerr, Kngwarray’s indigenous tongue and the name given to her people, whose permission was sought for this first solo exhibition of an Australian Aboriginal artist in the UK.

“You see an art on the walls that is about the moment when Emily executed these, but that moment of execution is about 65,000 years old…” says Nick Mitzevich, director of the National Gallery of Australia, which worked in partnership with Tate.

A panoramic film sweeps across ridges of red rock, clumps of bony trees and slabs of bush grass, making you feel you’ve entered Kngwarray’s ancestral domain. There are photographs of the pencil yam, its edible roots and underground seedpods, known as “Kam”, which is also Kngwarray’s bush name. The plant’s trailing trifoliate leaves bear a fortuitous resemblance to the three-toed tracks of the emu, an important animal in Anmatyerr Dreamings whose footprints are a delightful recurring presence in Kngwarray’s work.

Emily Kam Kngwarray began making art in her mid-60s at Utopia Station homestead, where she was living in the late 1970s. Before then, she looked after sheep, goats and cattle on “whitefella station” properties. Utopia homestead offered adult education courses to the women, including batik, an Indonesian artform where designs are made with melted wax on fabric to give a white line that stands out against the layers of dyed colour. Batik must have felt similar to cooking and washing, working on the ground in the open air, with cotton (and sometimes silk) stretched across a cardboard box or crate. Kngwarray was “the boss for batik” and spent 11 years making designs to exhibit and sell. A fantastic flutter of eight batiks, some two metres in length, is suspended vertically from the ceiling at Tate, each one distinct, ranging from the crush of waxed vegetal lines in Kam (1988) to those with more pictorial motifs, such as Emu Dreaming (1988) with its snake and goannas floating above fan flowers and woollybutt grass on a ground of antique ochre and earth colour.

Next door is a video of an “Awely”, a song and dance ritual in which a group of women grind pigments on a flat rock to use as body paint. They paint each other, smearing semi-circular collars of lines across the neck and shoulders of their partner, while breasts are barred with strong vertical stripes. This round-shouldered pattern also repeats in Kngwarray’s work.

The switch from batik to paint came in 1988-89. By this time, Kngwarray had tired of the hot-wax process: “I didn’t want to continue with the hard work batik required – boiling the fabric over and over, lighting fires and using all the soap powder over and over.”

Her decision coincided with the arrival of Rodney Gooch, a project officer from CAAMA (Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association) in Alice Springs. He distributed 100 canvases of equal size with tubes of ochre, black, white and red acrylic paint and encouraged the women towards this new and more lucrative medium.

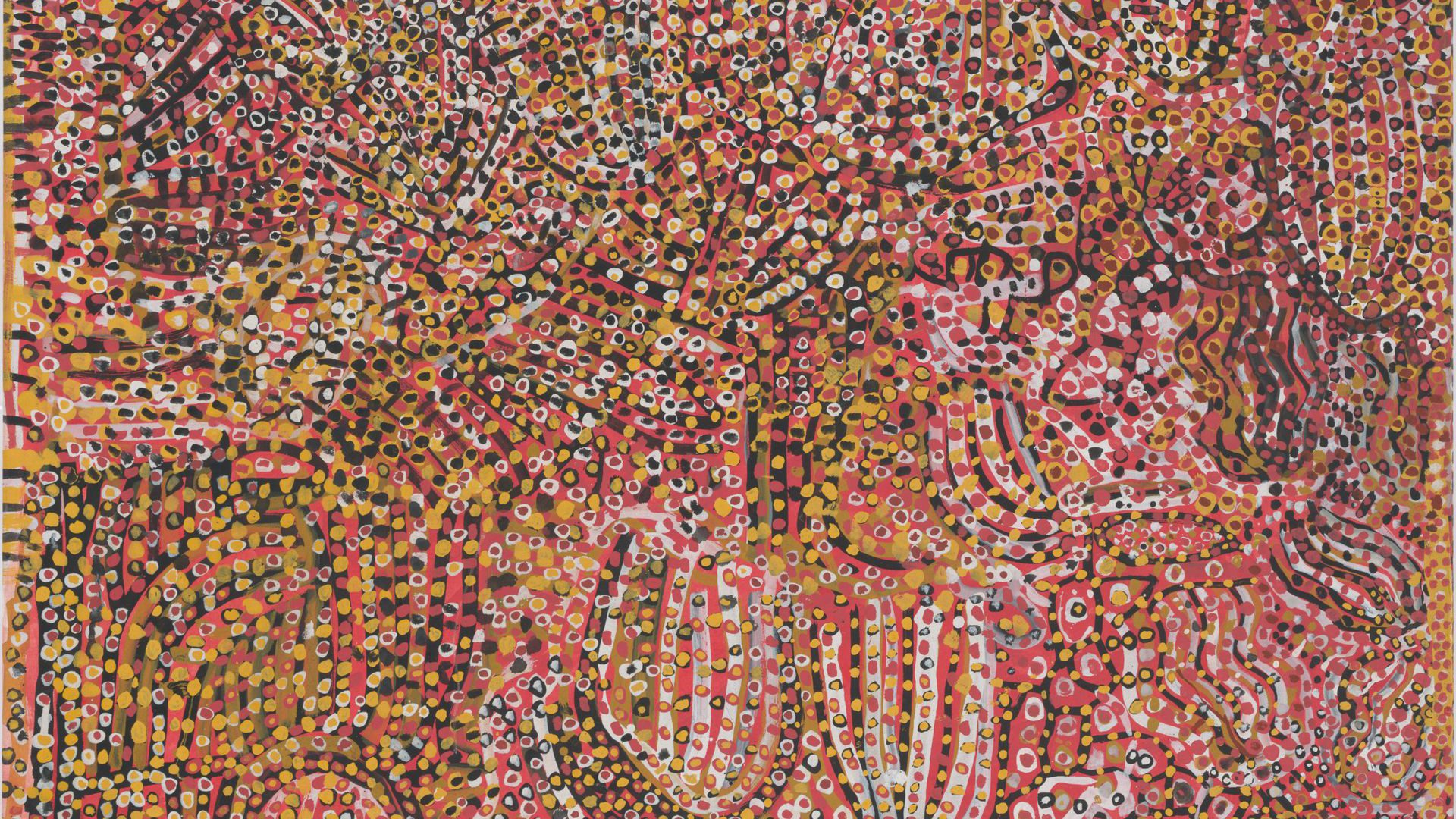

Kngwarray painted with hog-bristle brush and fingers, always working outside and on the ground, moving from the edge to the centre, using one colour at a time. Acrylic is fast-drying and can be watered down for thin washes or applied in thick brush strokes. Kngwarray loaded her brush and layered different colours so thickly that the surfaces sometimes look enamelled, yet they pulse with life, seeming to be made of something more than paint: to see her dotted canvases is to look through a microscope at the hoppity dance of microbes, or at starry constellations blooming in a night sky. For the artist, however, the canvases – like her body painting and sand drawings – are about Alhalker Country: “I keep on painting the place that belongs to me – I never change from painting that place,” she told linguist Jennifer Green.

In the final rooms, there is a flowering of both surface treatments and canvas formats. The boiling dots soften, melting into stippled fields of colour, as in the 22 paintings that comprise the Alhalker Suite (1993). Later, the colour fields and dots are stripped away, replaced by lines that race vertically down in black streams or lie horizontally in stripes of red, purple and brown (Awely, 1994; Not Titled, 1994). By then, Kngwarray was in her late 70s, yet the energy coming from the heart and hand of this artist is astonishing, lines that are frenzied, like the feet of dancers kicking up dust, lines that become translucent and ghost-like as the paint runs out.

Tate Modern’s show marks a welcome readjustment in the representation of indigenous first nation artists, and as Kngwarray’s art focuses on land, plants and animals, it is a timely reminder to remember our place in the larger picture of our world.

Emily Kam Kngwarray runs until January 11, 2026 at Tate Modern. Deborah Nash is a freelance journalist and writer who specialises in the arts