The news split my wife’s book group, and the WhatsApp exchange became testy. The division was caused by revelations in the Observer that the original predicament of Raynor Winn, author of the “journey-to-find-ourselves” bestseller The Salt Path – expulsion from an edenic cottage – had not been caused by a false friend mis-investing her hard-earned dosh. Instead it had its root in her embezzling as much as £64,000 from an employer who had trusted her, and – when discovered – borrowing thousands to pay some of it back and then not having the money to repay the loan.

One faction in the group was clear that the person to blame for the furore was Chloe Hadjimatheou, the journalist who had investigated Winn (real name Sally Walker). Their objection can be summarised as: doesn’t everybody make mistakes, wasn’t this just character assassination and aren’t journalists an untrustworthy lot? (A coda here: I have worked alongside Chloe at both the BBC and Tortoise Media and she is a highly trustworthy lot.) The other faction felt almost personally betrayed by Winn. The argument continues, but what was clear was that much had been invested in the book by its readers.

Getting on track

Until last week I’d never heard of The Salt Path. This isn’t so surprising because, as Richard Osman pointed out when discussing the controversy last week, most people have never heard of almost all books. And this one had passed me by.

Even if it hadn’t, I wouldn’t have read it. Long before its publication in 2018 I had grown tired of people finding themselves on journeys. Or anywhere really, but journeys are the worst. I watched the movie version of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail and liked it, but mostly because it starred Reese Witherspoon who I’d watch in anything. Had I been up for a self-discovery book in 2018, the year the Path was published, I think I’d have gone for Laine B. Brown’s Finding Myself in Puglia: A Journey of Self-Discovery Under the Warm Southern Italian Sun. “She knew no one and yet she had surety in her resolve,” reads the publisher’s blurb on Amazon. “She wanted to feel fully present in feeling unsafe and comfortable with the not knowing. And so the journey began…” I am not a sucker for redemptive arcs.

Just me here. No marketing budget, no promotion and no one telling me what to write. It’s a joy to do, but like all writers I need to be read. So please, please…

Ah, says the sharp-witted and incredibly well-informed reader, but wasn’t your own first book Paddling to Jerusalem (think Blake not Netanyahu) a very much less successful journey of discovery through England?

Yes, but not self-discovery. After three months travelling 1,500 or so miles in a kayak and on foot down rivers and canals of England I had discovered only a dislike of Canada Geese, a fear of swans, a wariness of anglers and been reminded of my own obstinacy.

The book is available free from all good garden walls outside houses whose occupants are moving; claim your copy quickly before it rains. And it was about discovering England at the turn of the millennium but doing it by water. In the event I was trumped by Roger Deakin who swam it.

My trip was uncomfortable, lonely and challenging. I had to parlay almost any random encounter into a meaningful exchange. Mostly everyone I met was lovely, which from a writer’s point of view is hopeless. When the woman on the next table poured a full glass of red wine over her rather seedy looking husband’s head in a restaurant beside the Trent, I could have kissed her.

“Funny” and “Aaronovitch is good company” were among my best reviews. Whereas The Salt Path garnered these:

“A beautiful, thoughtful, lyrical story of homelessness, human strength and endurance” – Guardian

“A tale of triumph: of hope over despair; of love over everything” – Sunday Times

“Mesmerising. It is one of the most uplifting, inspiring books that I’ve ever read” – i-paper

“The most inspirational book of this year” – The Times

“Luminescent. A literary phenomenon” – Mail on Sunday

This last week I read it. I noted its over-serendipitous beginning. In 2013, on the day after losing the court case for the possession of their home, Raynor and “Moth” Winn (aka Sally and Timothy Walker) get the news that his various aches and pains are caused by a neurodegenerative disease (CBD) which, at best, confers a lifespan of less than a decade. Days later, as the bailiffs are literally banging on their door, Raynor happens upon the guidebook to the South West coastal path and decides then and there that she and her terminally ill husband should walk its full nearly 700 mile length. With no money at all and being homeless (by choice, really) they will “wild camp”.

Some people have questioned whether this walk happened at all, to which I can only say that someone must have walked a lot of it. There’s too much checkable detail for it to have been an imaginative pull-together of Google Street View and Paddy Dillon’s guidebook.

As a book I did not find it lyrical or luminescent, but I can agree to mesmerising. It is by its nature immensely repetitive. The wind blows, the rain falls, the sun burns and you round Wotsit Point to see Hoocares Bay shimmering before you a dozen times or more. Ray and Moth are cold 100 times, dirty 100 times, have only fudge to eat 100 times, discover they only have £30 in their account 100 times. Moth is always on the verge of collapsing without ever actually succumbing.

Slightly more interesting is the low-level contempt the author displays for so many of the people she meets. They are mostly shackled to ambition, timetables, prejudices and materialism, whereas she – though homeless and cast out – is a free spirit and has been since she was a little girl refusing to marry a rich man’s son. In short, she’s an aging hippy of the kind I’ve known all my life. She spares us Buddhism though, and we should be grateful for that.

How to kill your husband

But two moments stood out for me as both very strange and revealing. Remember Moth has been given a diagnosis of this degenerative disease:

On p 75, as…

“…Moth struggled on, one thought had crept in; How stupid it was to be doing this, the irresponsibility of dragging him here. Clearly he was getting worse…

“What if by suggesting this insane trip I’d accelerated the CBD? It would be my fault. After all the consultant had said, ‘don’t tire yourself, or walk too far, and be careful on the stairs’.”

A paragraph later, she asks her husband:

“‘Have you taken the Pregabalin today?’ Moth had been prescribed this drug, not for its use as an antidepressant, but for relief from nerve pain. It seemed to work…

‘No, I took the last one at Baggy Point. I forgot to say, have you got another box?’

‘No, you’ve got them.’

‘I haven’t…’

How could we have forgotten them? As I thought about it, I could see them sitting on a bag in the back of the van ready to be put into the rucksack….

What had the doctor said? ‘Whatever you do, don’t just stop taking the Pregabalin’.”

Suggested Reading

A love letter to the Women’s Prize

There has been some scepticism about the fact that Moth seems in pretty good nick today, over a decade after that bleak diagnosis. But Walker/Winn does seem to have the letters proving the diagnosis was made (a note on that later). But what are we to make of a wife whose passionate love for her husband (as she tells us) goes far beyond the average, doing the two specific things that the doctors have told them both – in the clearest terms – not to do?

Given what she said she knew at the time, it’s nuts. She seems willing to risk her soul’s companion’s life because she didn’t fancy the accommodation they might have had to live in after the loss of their house. And not one reviewer, as far as I can see, even noticed this foible.

On stories and truth

Thirty pages later the Winn’s are given food and drink by Grant, a wealthy wine merchant who is under the misapprehension that Moth is really the poet Simon Armitage, who is also walking the Coast Path (a delusion shared by several other people they meet, which is odd because Moth and Armitage don’t look remotely similar).

The merchant tells them his rags to riches story in which – like Patrick Leigh Fermor in A Time of Gifts – he hikes penniless across Europe, but this time fetches up in Italy where he learns the wine trade. When he finishes his wife warns the Winns that it’s a fiction. “He studied wine at night classes and his father got him a job with a merchant he knew,” she says. Her husband responds by confiding that when he retires he wants to write.

“I believe I could be a great writer,” he tells them, “but it’s a good story isn’t it?” Winn writes, sympathetically:

“I thought about Grant’s tale and why he felt driven to tell it. When you tell a story, the first person you must convince is yourself; and if you can make yourself believe it’s true, then everyone else will follow. Grant wanted to be the person he had created: hard done by, struggling through life’s adversities, but making good on his own wits, rather than the son of a wealthy father with connections.”

Well, yes. “If you can make yourself believe it’s true, then everyone else will follow”. As long as you convince yourself of the story you’re telling, then it’s true enough.

No light, but rather darkness visible

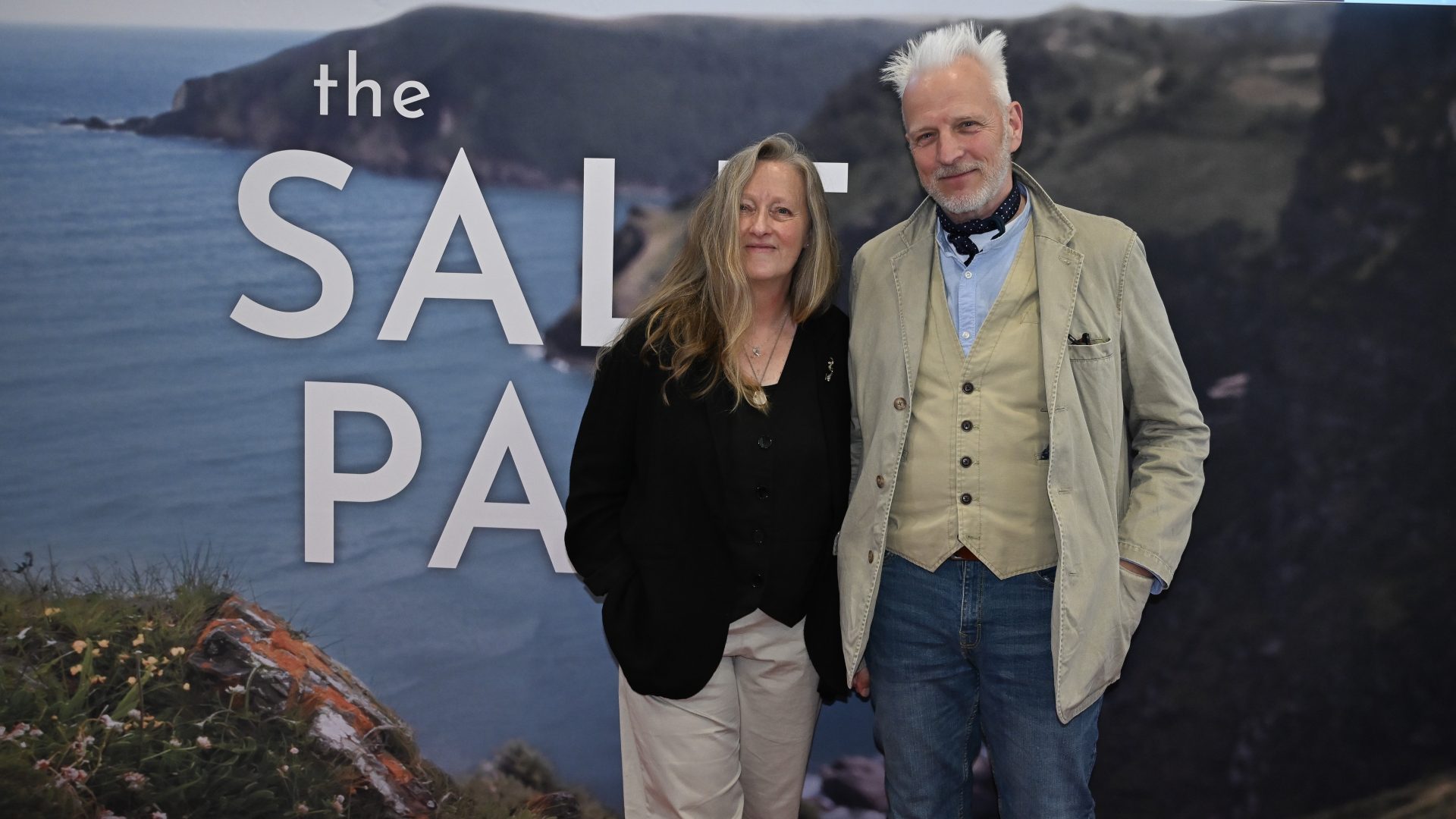

A few days after the Observer story ran, with her forthcoming book “delayed” by the publishers, but with the movie based on The Salt Path still in the cinemas, Walker/Winn responded to the allegations. The newspaper’s account of her life had been misleading, and the doubts cast on her husband’s condition were “vile”. Note: one oddity here is that the earliest letter of diagnosis that she republishes on her website is dated two full years after the house was lost and therefore long before they set out on their walk. I’m sure all will be explained.

Which it certainly wasn’t over the embezzlement charge. For a “luminescent” writer her language suddenly becomes opaque:

“I worked for Martin Hemmings in the years before the economic crash of 2008. For me it was a pressured time. It was also a time when mistakes were being made in the business. Any mistakes I made during the years in that office, I deeply regret, and I am truly sorry.

“Mr Hemmings made an allegation against me to the police, accusing me of taking money from the company. I was questioned, I was not charged, nor did I face criminal sanctions. I reached a settlement with Martin Hemmings because I did not have the evidence required to support what happened.”

“Mistakes were being made in the business” is a classic. The main mistake being made in the business was probably Martin Hemmings trusting Sally Walker.

The lust for authenticity

A few years ago I reviewed a book called Incest for The Times. It was an American woman’s graphic account of years of sexual abuse of the worst kinds inflicted by her middle-class father. When her publishers were asked about the book’s veracity they had replied, in effect, that they didn’t know, but that it was brilliantly written.

It was, but I wrote at the time:

“This is an odd defence of a memoir. The only requirement for this book to be considered valid is not the writer’s skill, but whether or not her story is true.

“And if it’s true, it’s a good if very uncomfortable book, and I recommend it to you. If not, then someone should be ashamed of themselves.”

The actual truth of a book that claims to be true and is sold on the basis of its authenticity, represents a contract between the writer, the publisher and the reader. The reader wouldn’t have bought the book had it been advertised as a work of fiction, and – for some time now – the lust for authenticity has seen memoir drive fiction out of publishers’ lists.

In 2003 a young writer called James Frey and the US publishing house of Doubleday (part of Random House) produced A Million Little Pieces, a searing account of Frey’s almost fatal addictions and his incredibly painful recovery. The book became a sensation and was sent into the bestselling stratosphere as a result of being highly recommended by Oprah Winfrey. Cue publisher’s joy.

In January 2006 an almost casual investigation by a little-known US magazine revealed that Frey’s account was largely fictional. Almost none of it had happened. The publishers apologised, compensated readers who complained and suffered the indignity of being slagged off by Oprah. Frey claimed that he had originally tried to sell the book as a novel, but only managed to stir up interest in the publishing world when he rebadged it as autobiography. Frey’s career has very much recovered.

Does it matter?

In 1995 a man calling himself Binjamin Wilkomirski published the episodic story of how, as a Jewish child in Poland, he had survived the Holocaust. The book – Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood – began:

“I have no mother tongue, nor father tongue either. My language has its roots in the Yiddish of my eldest brother, Mordechai, overlaid with the Babel-babble of an assortment of children’s barracks in the Nazis’ death camps in Poland.”

Here’s a horrifying passage of reminiscence:

“What I saw on the ground, up against the wall, was the two bundles, still lying there, or rather, what was left of them. The pieces of cloth or undone, lay around all torn, and in amongst them the babies on their backs, arms and legs outspread, stomach sore swollen and blue. And where once their little faces must have been, a red mess mixed with snow and mud.”

Wilkomirski, now based in Switzerland, became a celebrity. The New York Times described Fragments as a “slender, lyrical book [that] provides a fascinating psychological study of identity… he writes with a poet’s vision, a child’s state of grace.”

In April 1998 in Los Angeles a gathering commemorating the Holocaust was addressed by two child survivors: Wilkomirski and a woman called Laura Grabowski. Grabowski would tell audiences about how she had also been in the camps, where she had been experimented on by Josef Mengele and where she claimed to have met Wilkomirski.

Both were frauds. An investigation revealed that the author of Fragments had spent the war in Switzerland and that his real name was Bruno Grosjean. Laura Grabowski was a serial grifter called Laurel Rose Wilson, who had already passed herself off (not least on Oprah) as Lauren Stratford, a victim of Satanic Ritual Abuse, about which she had written a book called Satan’s Underground. Wikipedia notes that as of 2022 this last pack of lies was still available on Penguin’s list.

But before Wilkomirski was unmasked, Jewish organisations had praised the effect that the book had had on other child survivors and their willingness to come forward and tell their stories. You could almost argue, were you sufficiently perverse, that the damage was not done by the imaginative fraudster but by those who had outed him. I think the reverse is true: that people like him cause great harm, and that those who tolerate deliberate deviations from the truth, for whatever reasons, do violence to trust. Every time a fraud like this is discovered a Holocaust denier is born.

Winn some, lose some?

It may be that the embezzlement and therefore the spurious opening section of The Salt Path represents the full extent of Winn’s bamboozling of her readers. In which case many of those who have invested emotionally in her books may well forgive her. I honestly don’t know.

But there is something about her combination of mild contempt for the world of straight people, her belief in her own greater authenticity as a person, her developed feeling of victimhood, that together feel ominous. But then, perhaps – despite trying to repress it – I’m just jealous.

My own odyssey, described by the Guardian as “entertaining enough”, was somehow given the ISDN number of a defunct book. The result was that not only did Waterstones stock no copies, they told customers who inquired after it that the book no longer existed. It took me a month to persuade my publishers (“authors always worry about this kind of thing” they reassured me) to look into it. Then it was put on the “Jewish interest” shelf at my local bookstore and now, long deshelved, you can get a copy from Abe books, marketed as “Paperback. Condition: Good. Barely read, slightly faded spine.”

Says it all, really.

David Aaronovitch’s substack can be found here