Waiheke Island is a fashionable beach enclave with a strikingly proficient bus service that sits just off the coast of Auckland. It’s been dubbed “the Hamptons of New Zealand”, and while I can see what they’re getting at, I think that might be a bit much.

Spring was just kicking in when I visited the island in October, the recognisable feeling of a beach town returning to life after winter mirroring a slight relapse in my crippling jetlag.

When New Zealand author Janet Frame washed up on Waiheke in 1964, it was altogether a different place. The island contained “elements”. The first inklings of gentrification were spooking the locals.

Janet instantly felt a pervading sense of menace. She found the tropical climate oppressive. Unknown figures banged on the door of her remote cottage in the middle of the night and threw rocks through her windows. A freak accident on the ferry nearly decapitated her. She’d gone to Waiheke to find a peaceful place to work. She lasted five months.

She channelled her experiences into her sixth novel, A State of Siege, published in 1965. Even for Frame, a writer of deep oppression, it’s a claustrophobic read.

A retired schoolteacher (the remarkably named Malfred Signal), needing a fresh start, moves from the South Island to Karemoana (a fictionalised Waiheke) hoping to paint pleasant watercolours and start afresh. Instead, she’s tormented by an unknown assailant who violently bangs on her door in the middle of the night during a ferocious storm and refuses to stop. Paralysed with fear, she ruminates on everything that’s gone wrong in her life.

In the introduction to a new edition of the novel, published by Fitzcarraldo, Chris Kraus writes: “A State of Siege (SOS!) is an existentialist spinster-thriller – a book about creation and death.” Things don’t end well for Malfred.

Janet Frame is a writer who fascinates me. Her story is just so singular and miraculous. She’s something of a mystery, many of the smokescreens surrounding her life thrown up by the author herself.

I’d travelled to New Zealand to try to find some clues concerning Frame and decided to start on Waiheke. There wasn’t much there. The local bookshop didn’t stock A State of Siege, in fact, no Frame at all.

The cottage where she worked (or tried to) burnt down many years ago. I went to look at where it wasn’t. And then on my way home, just like Malfred Signal in the novel, I took a wrong turn and got lost in a mangrove swamp. These sorts of things seem to happen when you enter Frame-land.

Waiheke Island was the first place Frame moved to after a few prolific but fairly grim-sounding years in Europe. By that time, she was approaching 40 and was a fairly well-regarded, if hardly bestselling, author. But her journey to Waiheke was something of a miracle.

Born in 1924, her bleak upbringing was punctuated by poverty and tragedy (she lost two sisters in two separate drowning accidents). She spent much of her 20s in various horrifying mental institutions, diagnosed with schizophrenia.

She was about to undergo a lobotomy when her first book of short stories, The Lagoon, unexpectedly won a literary prize. A doctor happened to spot this in a newspaper, stopped the surgery and released her. Then, like Malfred, she moved from New Zealand’s pastoral South Island to the tropical north, living in a hut behind the cottage of legendary author Frank Sargeson. That’s where I headed next.

Takapuna used to be where Aucklanders went for their holidays. But as the city spread, it was subsumed into a suburb.

Sargeson moved into his primitive beach house in 1931. He became a celebrated short story writer and literary mentor for many modernist New Zealand authors. Impressed by her work, and intrigued by her story, Sargeson invited Frame to live on his property and write full-time. There she produced her first novel, the remarkable Owls Do Cry, published in 1957, which fictionalised elements of her early life, particularly the tragic death of her sister and the devastation she felt afterwards.

Janet’s hut is no longer there, but the house remains, miraculously saved from the creeping development around it and turned into a museum dedicated to Sargeson. It’s an astonishing place, unaltered since the author’s death in 1982. A photograph of a much older Frame dancing a jig in Sargeson’s bedroom, illustrates how much the place meant to her.

“After the war, there was a huge European émigré population came here with writers and artists and this place was sort of a centre for them,” Jenny Cole from the Frank Sargeson Trust told me. “Janet was able to write in peace here. She had that space to go further.”

And Janet did go further. Owls Do Cry is strange, disjointed, experimental and years ahead of its time. The work that followed, more than a dozen novels, plus short stories, poetry and essay collections, were powerful, poetic, dark and unique. Devoted to her work, she was critically lauded if criminally under-read.

She always enjoyed the devoted support of people, publishers, patrons, fellow writers like Sargeson, who appreciated what a singular talent she was and were determined to help her realise her writing vision. But it was always a struggle.

A huge turning point for Frame was the recognition of her misdiagnosis. Despite years of incarceration and hundreds of electro-convulsive shock treatments (and her planned lobotomy), doctors confirmed she had never been schizophrenic.

Some journalists, especially in her homeland, were too tantalised by the notion of this “mad” writer creating masterpieces. Stories about her tended to focus on this aspect of her life. Frame despaired and carried with her a doctor’s note, telling the world she was perfectly sane.

Perhaps it was these pressures that drove Frame into constant motion. She always seemed to be a writer in exile, even when she returned to New Zealand, moving home due to extraneous noise (lawnmowers being the worst culprit) or travelling abroad for long spells, despite her inherent seasickness and hatred of flying.

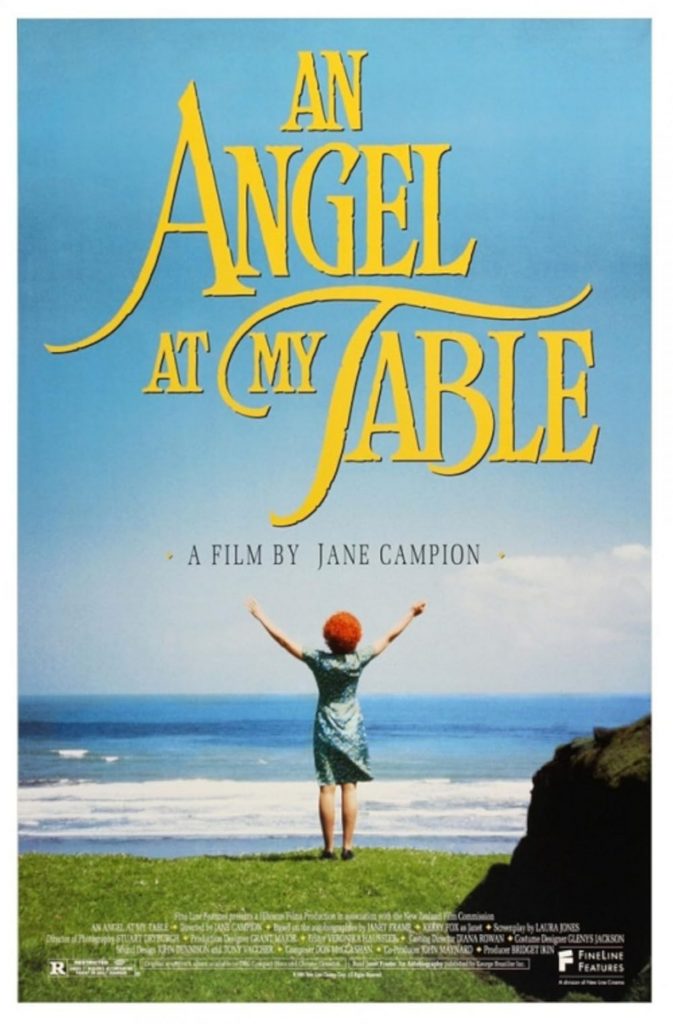

It was only when her three volumes of autobiography (To the Is-Land, An Angel at My Table, The Envoy From Mirror City), and more significantly, the filming of them by Jane Campion in 1989, that Frame finally felt financially stable and was recognised as an international literary star.

Much of her autobiography deals with events in the small, South Island town of Oamaru, where she was raised. If anywhere could lay claim to be “Janet Frame-ville” it’s here. But despite one of her childhood homes being turned into a museum, there’s not masses of Janet evident.

When visiting the town, I spotted a sign for the Janet Frame Heritage Trail, that appeared to lead nowhere. The Frame family plot in Oamaru old cemetery appears to have had few visitors lately. The library has some Frame-related bits and bobs located in a locked glass cabinet.

Instead, worryingly, the town has become the “Steampunk Capital of New Zealand”. The streets are cluttered with figures in Victorian garb and tourists taking pictures of figures in Victorian garb. It adds an additional strangeness to an already strange place.

The Janet Frame House is much more spacious than I’d imagined. But then, Janet was deeply involved in its development into a museum dedicated to her. It has some fascinating elements, especially to a Frame-head like myself. Perhaps it was the weird, falsified nature of Oamaru as a whole that gave the place an air of remove.

Unlike Sargeson’s, which oozes authenticity, Frame had insisted the house be revised and remodelled to her satisfaction. She wanted her vision of the past to be established.

“It’s very much in keeping with her autobiographies,” Rachel Fenton, the curator at the house on Eden Street tells me. “There’s a controlled narrative. She had no say over what happened to her throughout her entire young life. So, we have done what Janet wanted. We call it, pun intended, a reframing.”

It’s difficult to reconcile the squalor and tragedy that punctuate many of Frame’s books with the neat, airy Oamaru home. It feels like a monument to the upbringing that Frame desperately wanted and never got, bearing a slight historical revisionism that feels a kinship to the steampunkers down the road.

Suggested Reading

Turning over a new leaf: the books to watch out for this year

Janet Frame’s life ended where it had begun. The city of Dunedin sits 100 miles south of Oamaru and, on the day I arrived, resembled a small Scottish city in climate, architecture and attitude. Frame was born there, trained (but didn’t qualify) as a teacher, worked at the Grand Hotel, and was hospitalised at Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, just outside the city.

She returned in there in the late 1990s, joking that, ever the novelist, she was providing a natural, satisfying symmetry to her life. She died there in 2004, aged 79. Since then, her work has drifted in and out of print, as new readers have discovered her. New editions tend to appear in America or the UK (like Fitzcarraldo’s sterling efforts). It feels as if she’s appreciated more abroad, with New Zealand never quite sure what to do with her, especially now she’s gone.

There was little material evidence of Frame in the city of her birth. But this isn’t really a surprise. Frame was a writer, driven to write. She wanted to bury any clues that didn’t relate to the words on the page or offered easy answers. She was happy to distract people like me, desperate to apply some layer of easily ascribed understanding to her life and work.

Because her life doesn’t need it. The writing was everything. There are her books. That’s all that needs to be understood.

A State of Siege is out now, published by Fitzcarraldo

Dale Shaw is a TV and radio writer, journalist, musician and author of books including Painfully British Haikus