“Fun and exciting and adventurous

and she doesn’t look like anyone else”

Sophia, aged eight

Piet Mondrian was a dancer. Despite his reputation for being fairly humourless and remarkably eccentric (he harboured a crippling fear of both spiders and random eye injuries), the painter liked nothing more than to waltz, slowly and robotically. He once became so incensed by a rumour that the Dutch were planning to ban the Charleston that he vowed never to return to his homeland if they made good on the threat.

Mondrian was also a man obsessed by simplicity, austerity and primary colours. He lived in abject poverty, was constantly ridiculed by the art establishment and sold little during most of his career. He drifted from the Netherlands to Paris, then spent part of the second world war in London, occasionally sharing an air-raid shelter with Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. These many hardships were endured, to focus everything on his art, to the point where he refused any basic human relationships and subsisted mainly on lentils.

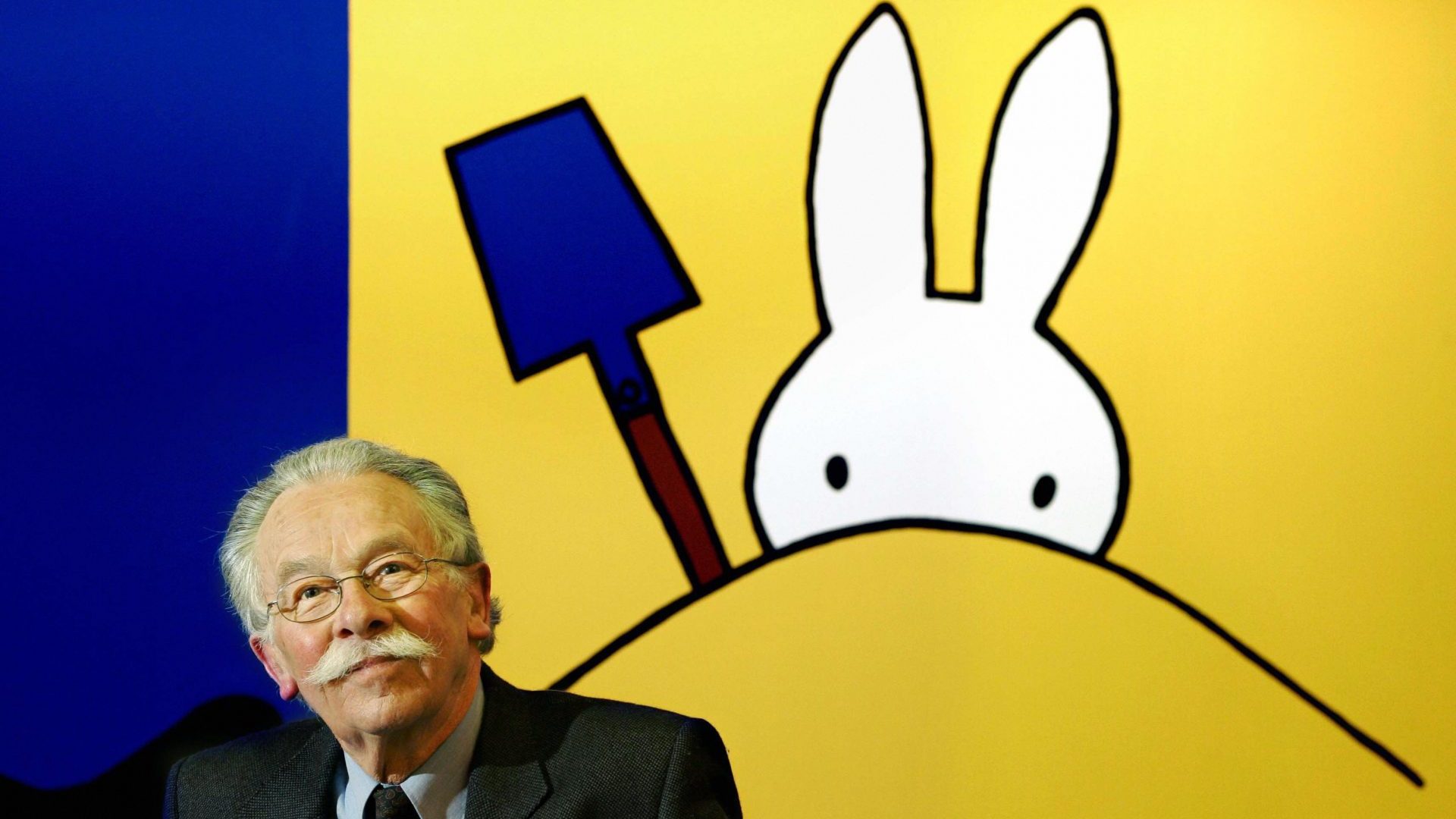

While Mondrian was being bombed alongside London’s artistic elite, 300 miles away in the Dutch countryside his compatriot Hendrik Magdalenus Bruna was also trying to avoid the Nazis. Born in 1927 (the Year of the Rabbit, according to the Chinese zodiac), Bruna was nicknamed ‘Dikkie’, or ‘fatty’. The moniker stuck and he was forever known as Dick Bruna.

Despite the threat of forced labour camps or worse if his family were discovered, Bruna said of these years of hiding from Hitler: “We had a pleasant time”. In true Mondrian style, Bruna was more scared of the spider-filled cupboard used as an air-raid shelter than the advancing Nazi hordes.

His was a bucolic childhood, filled with sunlight and animals and books and music. Born with congenital talipes equinovarus (or clubfoot), he spent a great deal of time lying down, staring out of the window and daydreaming. Windows would become an important motif in his later work. As Bruna told one interviewer: “From a point of seclusion, the outside world comes in…” He also began to obsessively draw, doodling on any surface that came to hand.

After the war, Bruna’s father, a noted Dutch publisher, wanted his son to take over the family business. But Bruna desperately wanted to become an artist.

As a young man, he was reluctantly sent away to learn the basics of publishing. He dutifully worked at WH Smith in London and Plon in Paris. But rather than providing an endearing love of bookselling, the journey just turned Bruna into a hardcore Francophile, obsessed with French chanson music and modern art. Léger and Picasso’s work impressed him, but Matisse stole his heart.

“When I saw Matisse’s work,” he said later, “especially his late collages, he became the most important man in my life.”

In particular, Matisse’s Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, with stained-glass windows, murals and even the priest’s vestments designed by the artist, would show Bruna the way forward.

Suggested Reading

Why ABBA still eludes us

“He’s cute. Oh, is it meant to be a girl? Well, it’s still cute,” Arthur, aged eight.

“A bobby mouse! No, a bunny rabbit!” Cora, aged two.

Both Léger and Matisse’s work sit alongside Bruna’s at an exhibition dedicated to Miffy’s 70th birthday at the Leeds City Museum. Miffy is Bruna’s most famous creation, selling over 85 million books worldwide and translated into 50 languages. But the beloved bunny is only a small part of the Bruna story. The exhibition showcases his influences and skills as a designer and storyteller. But, let’s face it, it’s Miffy who’s the draw.

“On the opening day of the exhibition, we had about 5,000 visitors,” Laura Irwin, the museum’s curator of exhibitions told me. “That’s an insane number for us. Probably the busiest that the museum has been since it opened.”

But it isn’t just toddlers toddling through the exhibit, as Laura revealed. “It’s been really obvious, over the last couple of months, how many 20-year-olds are interested. I think there’s an appeal for children with regards to the stories and the imaginative elements and the creativity of the books. But for adults, I think there’s also an appeal because the artworks themselves are so iconic.”

But it took Bruna many years of toil before the iconic figure of Miffy would emerge.

After finally convincing his father that he’d make a terrible publisher, Bruna offered instead to work as a designer for the family firm AW Bruna & Zoon. Like Mondrian and the artists and architects of the Dutch designers of the De Stijl movement, plus his beloved Matisse, Bruna became obsessed with the idea of simplicity in the graphic image. Clear, black lines, blocks of primary colour, no extraneous nonsense.

His book cover designs, which can be seen at the exhibition in Leeds, show this influence of Matisse and Mondrian, with simple, stark images and graphics that are eye-catching and singular. He created over 2,000 cover images for authors such as James Baldwin and William Faulkner, plus many crime novels including The Saint and Georges Simenon’s Maigret. Simenon was so taken with them, he wrote Bruna a fan letter, which Bruna cherished.

Bruna started dabbling with kids’ books; his designs appearing to be the perfect accompaniment for a child’s imagination. His first effort was The Apple in 1953. Then, a couple of years later, during a family holiday, everything changed.

Legend has it that the Brunas spotted a small white bunny gambolling though the sand dunes as they sat on the beach. Bruna expanded on the rabbit’s adventures during his son’s bedtime stories and soon began to illustrate them. As Bruna explains it, in his typically understated way: “Because I was an artist, I thought it might be nice to try to draw the rabbit.”

Miffy was born. Well, not exactly. In fact, Nijntje (Dutch for little rabbit) was born. She would become Miffy years later, thanks to the efforts of English translator Olive Jones.

But Miffy as we know her today took a while to develop. The 1950s incarnation of Miffy looked decidedly odd. The ears were wonky, the feet askew and she refused to look the reader in the eye. By the 1960s, as the books started to reach a wider, international audience, she started to transform.

Miffy slowly became rounder to make her more attractive to children, the language became simpler, while the stories added more emotional heft (Miffy’s grandmother dies in one book, quite a lot to tackle in around 150 words). Eventually, their iconic look was cemented. Small square books (an innovation at the time) resembling a window, with four lines of rhyming text on the left, and one bold bright picture on the right.

The simplicity was achingly attractive to kids of all ages. On to that minimal palette, a reader could project the emotions Miffy was feeling, plus any corresponding emotions the reader felt along with her. Miffy became a cypher for a child’s joy and fear and expectation.

But this simplicity was misleading. Bruna sweated over every image. Inspired by Matisse’s book Jazz, Miffy was first drawn on to transparencies, then paired with the correct bold colour combination, before finally being retransferred on to paper. Perfecting the image could take Bruna weeks.

He obsessed over getting Miffy’s blank expression perfectly aligned. A tiny shift in any direction could add or detract from the emotional effect he desired. He constantly reduced and erased, until everything was pure simplicity. As he told the Guardian in 2006: “At the end I have one big tear, and that is the saddest tear you can have.”

Once a book was complete, it was shown to Bruna’s sternest critic, his wife Irene. If she wasn’t instantly transported by what she saw, Bruna went back to the drawing board.

“I thought it was called Milly,” Sam, aged five.

Over the years, Bruna completed 34 Miffy picture books, plus 200 other titles. His life appears to be annoyingly idyllic.

Despite the multi-millions generated by book and merchandising sales, Bruna liked his life as simple as his illustrations. All he really wanted to do was draw.

He’d get up each morning, draw a small picture for his wife, cycle to the coffee shop, read the paper, then cycle to his studio and work the rest of the day. This routine continued until cycling became too much, and he retired in 2014, dying peacefully in his sleep three years later aged 89.

Though there won’t be any new Miffy releases from Bruna’s pen, the bunny in the tunic continues to captivate audiences. Utrecht is now practically Miffy City, with a museum, statues and a recreation of Bruna’s studio. As well as the exhibition in Leeds, there was a recent TV series, and the merchandising juggernaut continues to roll.

Like his heroes Matisse and Mondrian, Bruna created indelible, instantly recognisable images that burrow deep into the imagination. Using just two dots, and a cross for a mouth, he managed to project a childhood of emotions. He made the world slightly safer, less confused and a brighter place for little people everywhere.

Miffy’s 70th Birthday is at Leeds City Museum until September 7, 2025

Dale Shaw is a television and radio writer, journalist, screenwriter and musician