In the summer of 1963, Downing Street (or, rather, Admiralty House, serving as a substitute for No 10 during renovations) felt under siege; the sense was of a prime minister’s grip no longer holding. A great scandal was about to engulf Harold Macmillan. The charge was dereliction – a failure to heed warnings about a cabinet minister.

For weeks, I had, with my two colleagues of the founding Sunday Times Insight team, Ron Hall and Jeremy Wallington, been piecing together the origins and path of the scandal surrounding the man who would give his name to it, the secretary of state for war, John Profumo. I had been regularly admitted into the prime minister’s office for off-the-record briefings from his chief press officer, Harold Evans, a trusted career civil servant. The deal was that I would tell him what we knew and he would either confirm or deny it.

By the end of May, we had reached a state of critical mass – collating many sources into a timeline, basically who knew what and when did they know it? On May 28, I presented our final checklist, and Evans confirmed some details and corrected others. A single damning detail stood out: It had taken 123 days for one critical piece of information from the security services to reach the prime minister, in itself enough to have brought down Profumo. For four months, Profumo had consistently lied to parliament, to his colleagues and to the prime minister and, moreover, had suppressed with threats of libel action anyone challenging his story.

Macmillan now knew that on January 26, the security services had seen the text of a police interview with a young woman named Christine Keeler in which she said she had been sleeping with both Profumo and a Soviet spy. That evening, Macmillan initiated an investigation led by the Lord Chancellor. (Two days later, Eugene Ivanov, the spy, fled to Moscow. Pillow talk had provided nothing of value.)

That afternoon, I asked Evans how Macmillan felt. The prime minister, he said, had told him that he had “lost my zest but my spirit is not broken.”

Late on June 4, in a personal letter to Macmillan, Profumo confessed – “I cannot tell you of my deep remorse for the embarrassment I have caused you…”

“Embarrassment” fell well short of the damage done to Macmillan and his government. The system of internal checks had failed the man at the top. But Macmillan was also at fault. Well aware that the chattering classes were chattering about little else than lurid rumours about Profumo, he was incurious to the point of somnolence and too easily taken in by Profumo’s lies.

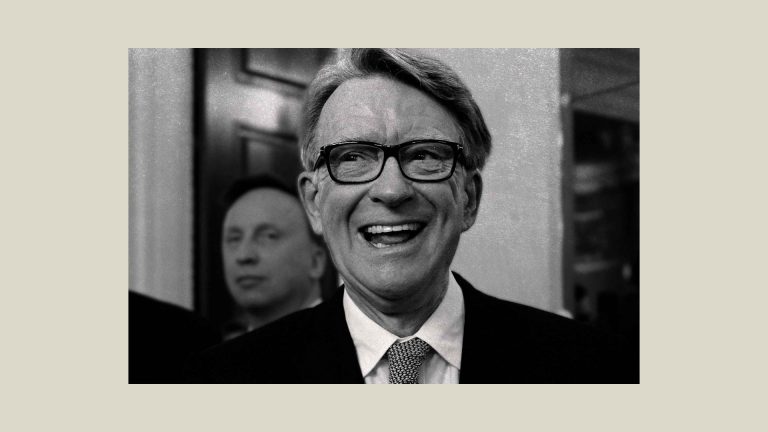

Peter Mandelson is in a different league as a liar. Comparisons of the two scandals do not persuade.

The principals are so different. Profumo was a political lightweight with the sexual appeal of a lounge lizard. For Mandelson, the reptile smart politician, the aphrodisiac was money – those with lots of it and their largesse. Macmillan was a consummate cold war statesman, using the last of Britain’s hard power to mediate between Washington and Moscow. Keir Starmer’s legacy will be that of an earnest and committed agent of soft power and a failed party manager.

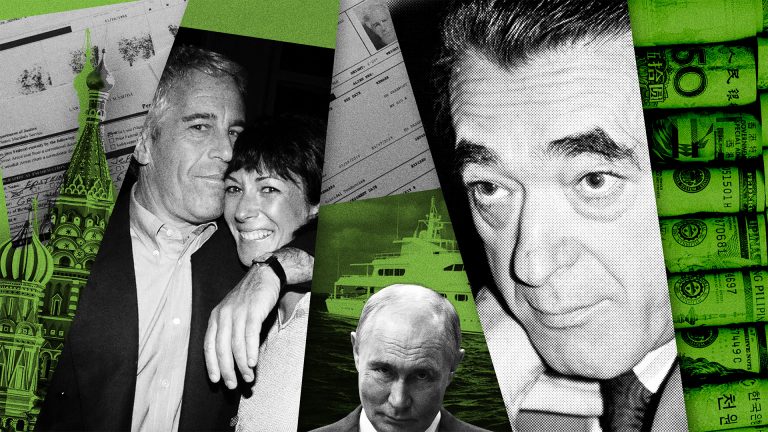

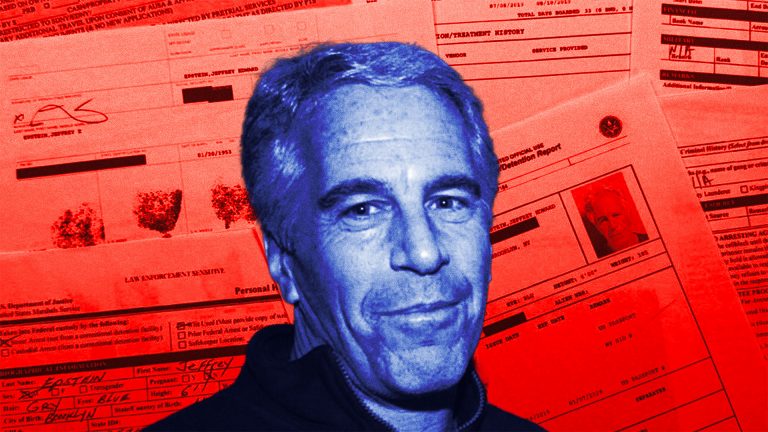

There are superficial similarities, though. Profumo’s coercive use of the libel laws to silence newspapers is mirrored by Mandelson’s effective gagging of reporters who were on to him – notably at the Financial Times. They finally won some retribution by running a photograph of him in residence at an Epstein mansion in minimal underpants, talking to a young woman in a bathrobe whose face had been redacted.

Suggested Reading

Mandelson in hiding: A ‘New Yorker’ profile

There was no Epstein in the Profumo landscape. Instead, there was the osteopath Stephen Ward, who acted as a host and complicit social director to Keeler and her more mature close friend, Mandy Rice-Davies. Ward was notably uninterested in money and had no agency over the girls, but his fate was to be dumped by all his celebrity clients, framed as a pimp and driven to suicide.

There were, however, very young girls. Keeler was just 17 when she qualified for the sobriquet of “showgirl” at a club where roaming males came to ogle and often proposition backstage. Photographers picked up on her resemblance to the “nymphets” of Nabokov’s Lolita, culminating in one shot discreetly masking her nudity with the curves of a plywood chair that she straddles. She was suddenly world famous but marked for a troubled life, as have been many of Epstein’s victims by their experience at the hands of powerful men, yet to be unmasked.

After Profumo was disgraced, Macmillan was defensive about his reluctance to accept the rumours about him. He said, “If the private lives of ministers and of senior officials are to be the subject of continual supervision day and night, then all I can say is that we shall have a society very different from this one and, I venture to suggest, more open to abuse and tyranny than would justify any possible gain to security in the ordinary sense.”

But Macmillan had been living with his own secret wound for decades. Since 1929, his wife, Lady Dorothy, had been the mistress of Lord Robert Boothby, for decades a major Tory party player and, as later revealed, an ardent bisexual with a taste for rent boys. I was told by Randolph Churchill that Macmillan had been cuckolded but there was no way it could be publicly revealed.

It was, obviously, the key to Macmillan’s fatal aversion to knowing about the private lives of others, no matter how vile they were. But our Insight book, Scandal 63, was silent on that.

Clive Irving writes for Vanity Fair and the Daily Beast. A former managing editor of the Sunday Times, he is the author of The Last Queen, about Elizabeth II