Cascades of arum lilies and other blooms ingeniously gathered in the winter of 1939 spread from the coffin at the heart of the Kröller-Müller Museum. The matronly figure of Van Gogh’s Madame Ginoux – L’Arlesienne – looked down comfortingly from the walls. And directly above this sombre scene, Vincent’s Four Sunflowers Gone to Seed chorused both their lament and their consolation: yes, the once bright heads are bowed, but their seeds promise colour anew.

For 24 hours before her simple country funeral, Helene Kröller-Müller was surrounded by the paintings that were her passion. Today, they are enjoyed by visitors to the national park in Otterlo, near Arnhem, in which the museum that bears her name houses treasures from five centuries of art.

Born in 1869, Helene was largely raised in Düsseldorf, her father having founded an import/export company with branches in London, New York and Rotterdam. Among his employees was the very bright young Dutchman Anton Kröller, and a marriage between him and the intellectual 19-year-old heiress was encouraged. Four children were born, among them a daughter who showed an interest in art.

An expert art lecturer, HP Bremmer, became Helene’s personal tutor and adviser, and the Müller fortune was ploughed into a personal art collection that would exceed 11,000 works. A first purchase was a rural scene by Paul Gabriël, unexpectedly punctuated by the modernity of a stream train and telegraph wires.

Almost from the outset, it was Kröller-Müller’s intention that this feast of art would eventually be opened to the public, and life-threatening surgery in 1910 caused her to consider the future of her growing collection. At the same time, she expressed admiration for the philanthropy of earlier collectors, such as Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, the last of the Medici dynasty, whose gift of art was the bedrock of Florence’s Uffizi galleries. While Kröller-Müller survived her treatment, the idea of an accessible collection for the enlightenment and betterment of the public did not go away.

But first came shopping sprees that rang up many zeros. In 1912, she really let rip, buying a whopping 32 works, including no fewer than 15 Van Goghs alone, at a cost of 210,000 French francs plus 30,000 German marks. This haul, which included La Berceuse, is now priceless. The last big splurge was in 1928, when she spent 100,000 francs on scores of pieces.

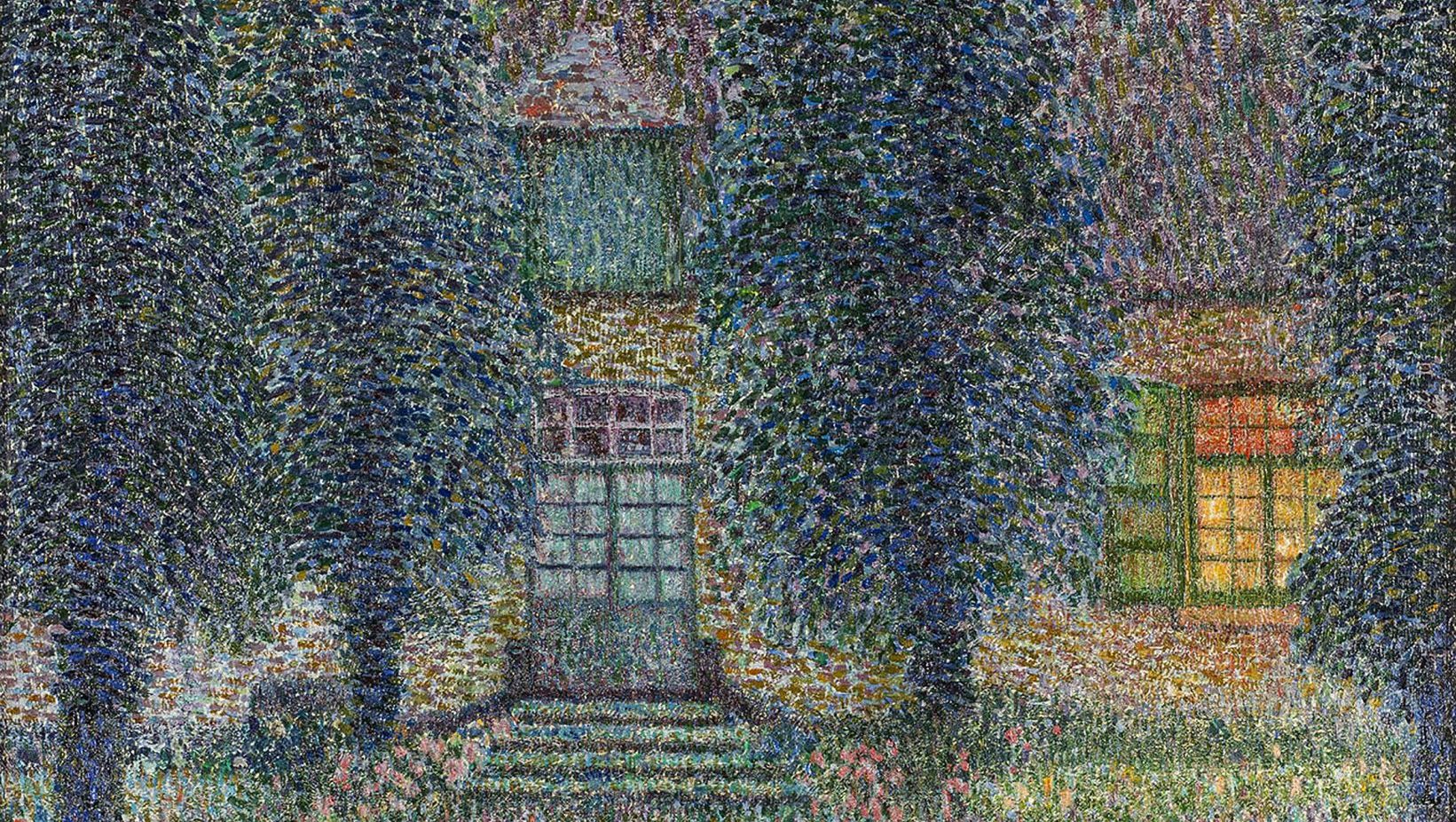

In her search for spirituality in art, and with the help of Bremmer, she focused increasingly on the short-lived Neo-Impressionism movement. This explosive period in art history was dominated by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, with their groundbreaking experiments in colour. But to Kröller-Müller, theirs was far from a theoretical and analytical approach: it was in their works’ serenity and tranquillity that she found her peace.

At the same time, she was working quickly to establish a purpose-built gallery, initially in The Hague, where the couple were raising their family. In 1920, Kröller-Müller embarked upon a bigger museum, this time on the family’s vast hunting estate south-west of Amsterdam. Here she would show and share her collection of man-made beauty amid the natural beauty of parkland and woods.

The final result, a gallery completed in 1938, is at the heart of today’s much expanded Kröller-Müller, now ranked as one of the Netherlands’ top art museums. Today it is the custodian of more than 40,000 works.

Suggested Reading

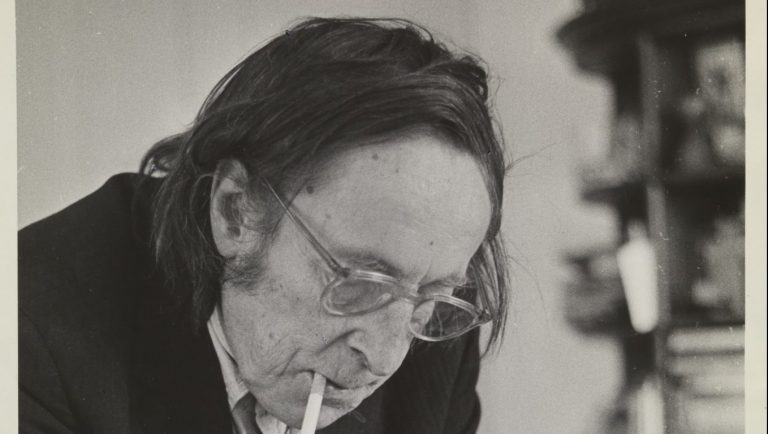

Edward Burra, the artist who wasn’t interested

While her husband funded the rapidly growing collection, not least with his eye for a business investment, the collection was very much one woman’s project, albeit with guidance from Bremmer. She drove the building plans too, working with the architect and artist Henry van der Velde. He understood the need for natural light, which falls through ceiling lanterns, and it was he who tucked the single-storey building into the folds of the surrounding landscape.

This first incarnation of the Kröller-Müller opened on July 13, 1938, but by then the Müller family fortune had been lost. Overstretched by loans as the company thought bigger and bigger, it had been a victim of the great crash of 1929. The project became a collaboration between Kröller-Müller and the Netherlands’ public art body that runs it to this day.

Extensions opened in the 1950s and the 1980s, the latter glass-sided, eliminating the boundary between art and nature. On the cards now is yet another extension, to open in around six years’ time, doubling the display space and diving underground.

In the meantime, an unprecedented loan to the National Gallery in London of more than 30 works from the collection underpins a new exhibition that will shed light on the influence throughout modern art of groundbreaking Dutch and Belgian groups – Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists.

The exhibition reminds us of the shock of the new, and of 1886, a pivotal year for modern art. This was the year of the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition in Paris. Among the works on display was Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, now one of the outstanding treasures of the Art Institute of Chicago, where it stops visitors in its tracks with its monumental celebration of summer pleasures, shared and yet solitary.

The same artist’s dance-infused La Chahut (1889-90), bought by Helene Kröller-Müller (who narrowly missed out on acquiring La Grande Jatte), is set to make a similar impact when it arrives in London. And a second work, hugely influenced by La Grande Jatte, Théo van Rysselberghe’s In July, Before Noon or The Orchard (1890), with its six women enjoying summer in companionable silence, is similarly set to be a favourite exhibit.

It is almost impossible to exaggerate how much La Chahut upset the apple cart. Its four high-kicking dancers, two male, two female, its pig-like voyeur, its glimpse into the orchestra – a bit of double bass, a bit of flute, nothing in between – baffled many of its first viewers. What was the artist thinking of, capturing this unseemly scene, cutting and dicing the image with his diagonal lines and colour spots? More, he painted right round the image and then on to the frame itself, breaking the cordon sanitaire between the image and the world.

In Van Rysselberghe’s Grande Jatte tribute act, the outdoor scene is less rumbustious, but equally compelling. The artist’s future wife and her female friends and relatives are intent on their individual pursuits, sewing, reading, gently handling flowers. The colour palette of soft greens and blues in fact relies on complementary colours, reds and yellows.

The influence of Seurat and of the other Neo-Impressionists would extend long beyond their short-lived movement. Later artists would pursue the pioneers’ sense of geometry, ultimately pushing the boundaries to pure abstraction. Others would experiment further with detaching colour from pure representation and treating it independently. Today’s Kröller-Müller explores these unfolding stories to their outer limits.

Helene Kröller-Müller died only one year after the opening of the gallery that she lived and breathed for half of her 60 years. The gallery’s Van Goghs, including those under which her coffin lay, represent a collection that is second only to the world’s largest, held at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. But that is only the start of her legacy.

Radical Harmony: Helen Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists is at the National Gallery, London until February 8

The Kröller-Müller Museum and Sculpture Garden, Otterlo, Netherlands, is open Tuesday to Sunday