In the Chinese language, there’s no shortage of sayings about the importance of gaining wisdom by learning history. One prominent Chinese proverb “温故而知新 (wēn gù ér zhī xīn),” literally translates as “reviewing the old and acquiring new knowledge,” emphasising that by reflecting on the past, one can gain fresh understanding.

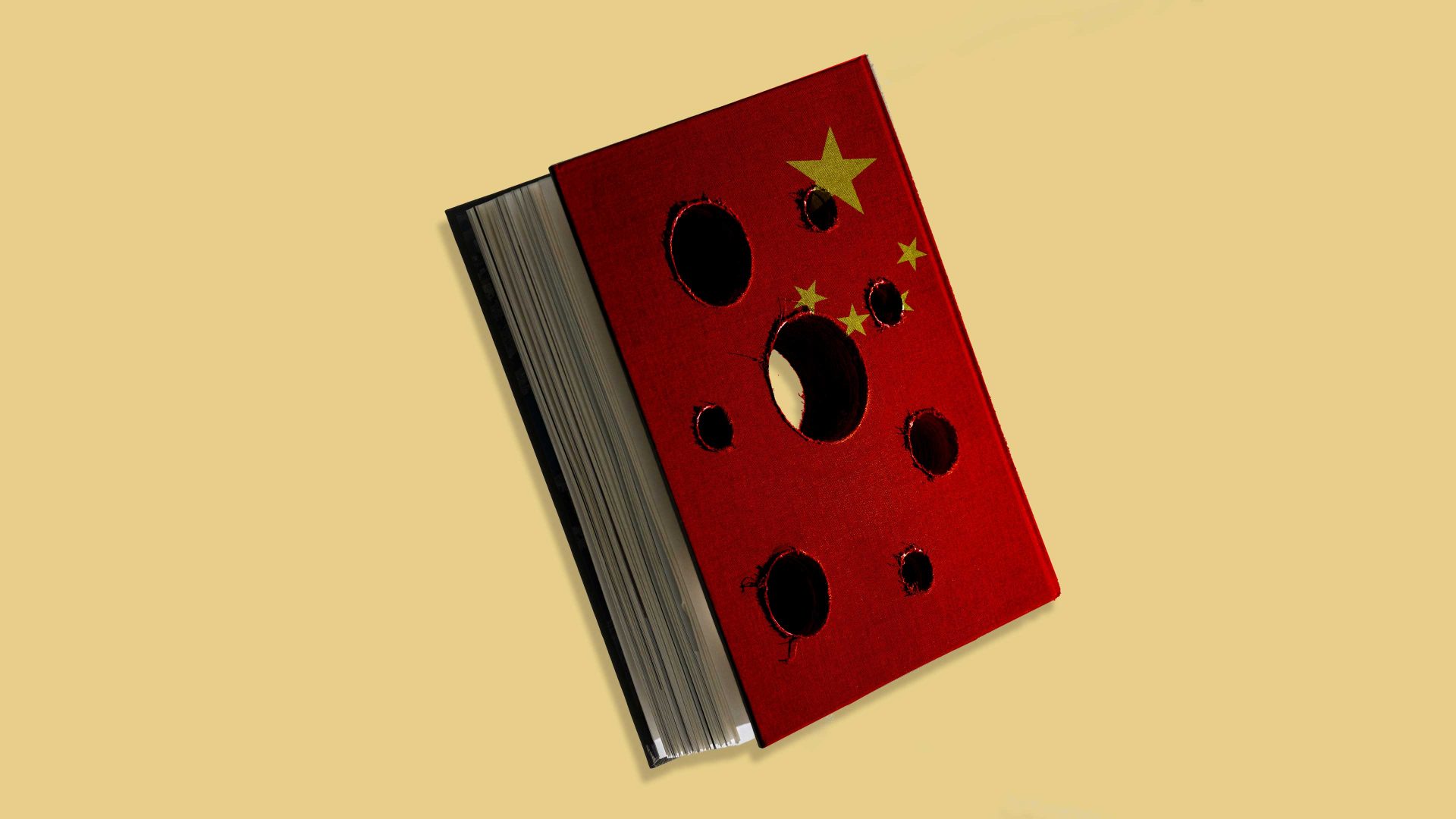

But perhaps more than western countries, China finds it hard to confront the dark chapters of its own history because it doesn’t have a democratically-elected government, which makes openly revealing or analyzing historical mistakes by the ruling Communist Party potentially threatening to its legitimacy and so to its one-party rule.

Downplaying or even reinterpreting historical events that could show the government in a bad light are common. The Great Leap Forward, a disastrous campaign of industrialisation which was launched by chairman Mao Zedong and ran from 1958-61, resulted in tens of millions of people starving to death. It is acknowledged as a disaster, but the human costs are downplayed and the leadership’s responsibility is airbrushed out. The Cultural Revolution (1966-76), during which the country’s youth were whipped into an extremist fervor to help Mao attack his ideological enemies within the party and maintain control, led to millions of deaths from violent persecution.

But while the official narrative acknowledges that the Cultural Revolution was a mistake, it does not delve into the party’s responsibility but instead emphasises its role in carrying out the ensuing reforms. And the June 4, 1989 massacre of hundreds and possibly even thousands of pro-democracy student protesters by China’s military in Tiananmen Square is justified as the quelling of a counterrevolutionary movement that threatened national stability.

When it comes to other countries’ historical wrongdoings against China, however, there’s no shortage of detail, not only in school textbooks, but in TV series, movies and videos that are circulated on social media.

The most recent examples of this were the many reminders throughout September of the atrocities committed by Japan against the Chinese people during the second world war. These were intended to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of the war in China, which is known as “Victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression”.

State-run media carried extensive reports on the anniversary. Exhibitions were held. A historical film drama “Dead to Rights”, based on true events, was released. It tells the story of a group of civilians who sought refuge in a photo studio during Japan’s invasion of Nanjing, then China’s capital, and who risked their lives to expose the brutal massacres and rapes committed by the Japanese Imperial Army.

People generally agree that the history of these devastating atrocities and of foreign invasions and occupations of parts of China must be taught, and that stories of national resilience are useful in fostering a sense of unity and patriotism. The worry is that the relentless focus on the wrongs committed against China, especially by Japan, could push people far beyond pride and into hatred.

“I think it’s too much,” said a young Chinese friend, who grew up in the mainland but now lives in Hong Kong. “If you’ve grown up in that education system, you will naturally have nationalistic views, because the whole narrative is that our Chinese nation was under humiliation and oppression, and we escaped from this.”

Suggested Reading

Does China have its eye on Siberia?

A middle school teacher in China told me: “Hatred of Japanese is very high among the young people I come in contact with because they haven’t been taught anything else.”

“From the time they are young, they will learn that Japan invaded us; they see this from watching TV at home, mostly movies, which only speak of bad things,” she said.

In recent years with the US-China rivalry over trade and technology, and disputes over Taiwan and the South China Sea, they have also begun teaching hatred towards Americans, she said.

The teacher, who is in her 30s, had access to Google when she was growing up, but her students are mostly born after 2010, the year when the company stopped providing its search engine in China due to demands that searches should be censored. She said she was alarmed by their reaction when she showed a clip of the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York.

“After watching, they were applauding. I asked them ‘what if this happened in Japan?’ They were happy,” said the teacher. “When Japan is struck by typhoons and earthquakes, they would also think it’s good, that it’s better if more people died.”

The government has denied that the education system promotes hatred, despite tensions with Tokyo in recent years over its siding with the US on various geopolitical issues and the two countries’ unresolved territorial disputes in the East China Sea. Officials stressed, as with the 80th anniversary celebrations, that they want people to remember and learn from history, cherish peace and prevent the tragedy of war from happening again.

But the anti-Japanese, anti-American and nationalistic rhetoric affects people, especially youngsters, who lack the real-world contact with foreigners that comes from working for multinational companies or travelling abroad.

I encountered this recently while having lunch with a young relative. He referred to Japan as “the country nobody likes”. I immediately found myself telling him he should not blame ordinary Japanese people, for they were also victims of their past government’s actions.

In recent years, the Chinese government has made it harder for residents to jump over the so-called “Great Firewall” by using proxy servers (VPNs) to access a wider source of information from websites outside China such as Google, YouTube or Wikipedia. Teachers who try to present more information than what is set out in textbooks risk disciplinary action.

It’s actually the TV, online videos and movies that have the greatest impact, my friend tells me. “China’s movie industry emphasises patriotism, so a lot of movies focus on that… There are a lot of movies on the war of resistance. In recent years, there have been some about the Korean War.” When it comes to producing films with any political theme, the restrictions are heavy.

The government’s aim is to build unity and a sense of patriotism, but Chinese citizens are already some of the most patriotic in the world, from what I’ve seen. As China has now developed into a world economic, technological and military superpower, the risk is that it still sees itself not only as a victim of the past, but potential victim in the future, constantly having to bring up past wrongs, and influence how its people view those it sees as responsible.

That approach to history has the potential to affect China’s foreign relations. If the Chinese people, including future generations of leaders, are resentful of Japan and of the west, the risk is that it will affect China’s future relations with those countries.

Will it inevitably turn out this way? That’s a difficult question to answer – and in China, it’s an even more difficult question to ask.