Picture the scene. São Paulo, 1950, the sun is high and two young women are climbing up to the Monument to the Independence of Brazil on the banks of the Ipiranga Brook. They’re in jaunty summer hats and alone on the vast stone steps. Pausing halfway up, one of them points up ahead at something out of frame and the pair gaze aloft. The moment was caught by José Yalenti, a young amateur photographer. In its way, Yalenti’s snap – which he titled Parallels and Diagonals – is a portrait of modernity. His lens isn’t interested in the baroque pomp of the sculpture, it’s focused on the geometry of stairs.

Yalenti was a founding member of Foto Cine Clube Bandierante (FCCB), a group of enthusiastic and experimental weekend photographers active in São Paulo from the 1940s to the mid-1960s. Several of his pictures now feature in Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1939-1964, a new volume surveying a little-known movement that flourished in Brazil’s 20th-century heyday.

The club was founded in 1939 just as São Paolo was entering a period of prosperity. This was a time of Oscar Niemeyer’s architecture, a property boom, American investment, Cinema Novo and bossa nova on the radio. At FCCB a coterie of enthusiasts helped bring photography into this hothouse. These were businessmen, engineers, biologists and bankers – there was even a lepidopterist. All of them had caught the shutter bug.

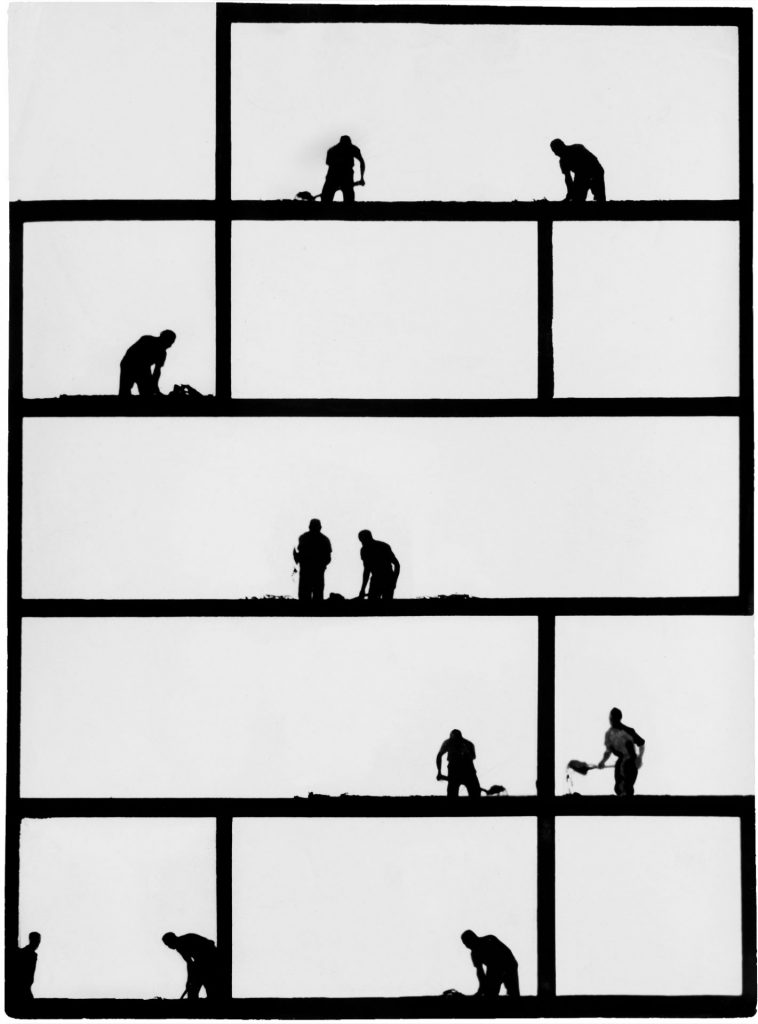

While styles initially leant towards pictorialism, as the urban development of São Paulo grew, a new modernist photographic aesthetic took hold. Each member had their own approach. Geraldo de Barros, a key founding member and an employee of the Banco do Brasil, was celebrated for his Fotoforma series, in which he used multiple exposures, negative collages and photograms to create dizzying geometric compositions.

His friend German Lorca, an accountant from a Spanish immigrant family, began using a Kodak as a teenager and was soon shooting futuristic cityscapes and angular figurative works that look like stills from a film noir. Geraldo and German would work in the lab together.

Having fled the Spanish civil war, the Catalonian Marcel Giró wound up in Brazil where he perfected a distinctive pared-back approach to architectural studies and street photography. And Thomaz Farkas, a Hungarian immigrant, created the club’s cinematography department. These and many more would become known as the “Escola Paulista” – the São Paulo School.

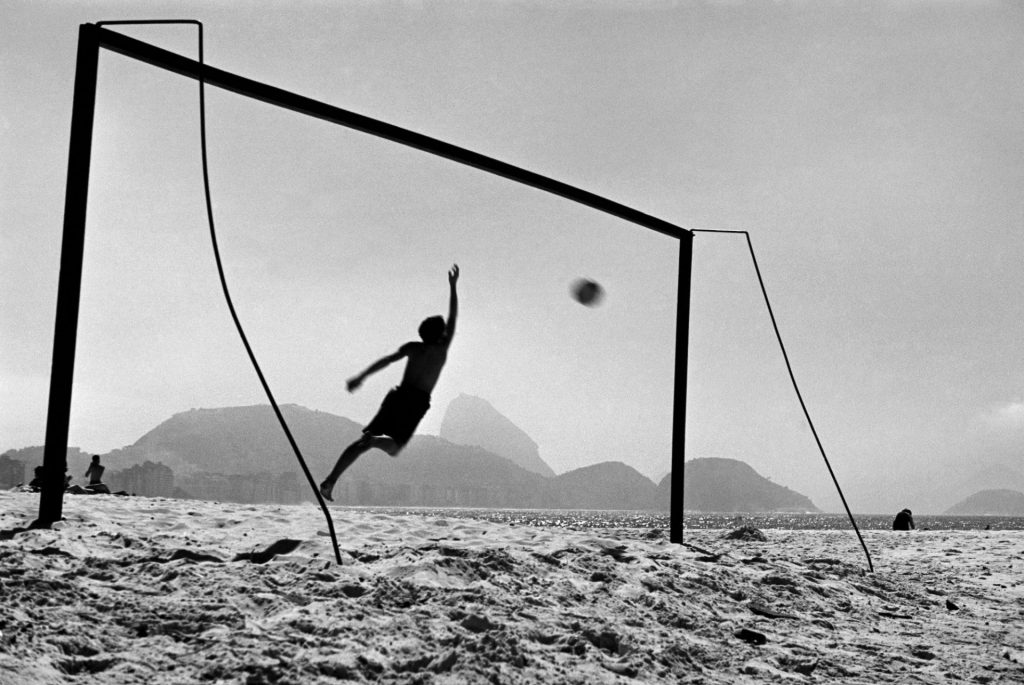

Collectively, their pictures are a revelation. It’s like finding an outpost of Bauhaus in the tropics: abstractions formed from structures, sky and shadows; figures dwarfed by boulevards and buildings or starkly silhouetted against walls; collages of shapes formed by the white-hot light. Some members delighted in the possibilities of the darkroom.

Despite its formal adventurism, the FCCB could be remarkably stuffy at times. Like most competitive male-centric environments, it liked its rules. “I had lots of arguments with other photographers in the club because my ideas and vision of photographic art diverged from theirs,” recalled de Barros. “They had an academic vision of photography, whereas I was more of an ‘inquisitive’ sort, always seeking out unorthodox solutions for my art.”

And then there was the issue of women – there were no women among the 32 original members. When Alice Brill joined, the German-born Brazilian brought a strong humanist slant. Her pictures of shoeshine boys and billboard posters show a more ragged city. Arguably, the most prominent female photographer in the group was Gertrudes Altschul, a German Jew who had escaped Nazi Germany for a new life in South America. Her botanical studies are masterpieces of abstraction.

Suggested Reading

The Brazilian motorway that thinks it’s a park

The club thrived for a quarter of a century. Members went on photography trips together, ran courses, organised competitions and promoted their medium in the city’s art museums. They also published a regular magazine, the Boletim Foto Cine. The club’s golden age came to an end with the civil-military coup of 1964, although the FCCB is still active today, and is run out of a building on Augusta Street.

In 2021, MoMA in New York staged Fotoclubismo, an exhibition of around 60 works by the club’s photographers, drawn from the museum’s own holdings. This summer a selection of FCCB works can be seen at Les Rencontres d’Arles photography festival, curated by Helouise Costa and Marcella Legrand Marer, co-editors of the photobook.

The work of the FCCB captured the period of Brazilian history when the nation grew in energy and prosperity. An editorial in its bulletin summed up its importance: “They managed to detach themselves from the old, bucolic genres,” it said. The new photographers, it says, began “delving into the asphalt to extract images that palpitated with a sense of the now.”

Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1939-1964 is published by Atelier EXB. Christian House is a freelance arts and literature journalist