Next year marks the 50th anniversary of punk rock’s birth – except it really doesn’t.

The first British punk singles, New Rose by the Damned, and the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy in the UK, were released within weeks of each other, on October 22 and November 26, 1976. Then the Pistols’ infamous TV interview with Bill Grundy on December 4 put the movement on tabloid front pages, where it would stay for a couple of years.

Yet many pundits make a convincing case for punk actually being born in London a year earlier, in 1975. Others contest that the initial concept was an ever-evolving American mishmash later imported to the UK by Malcolm McLaren via his dalliance with the New York Dolls.

I’d say that the roots of punk are buried far, far further back than the Dolls, the Stooges, the Monks. For me, punk rock is not just a youth culture or musical genre – it is a mindset, a tenet, that entails questioning and challenging traditions, beliefs and the prevailing status quo. That is a philosophy, however subliminal, that has existed through time.

As well as taking aim at sacred cows, an essential part of the punk profile is to do it yourself. McLaren couldn’t get the Sex Pistols booked, so he hired the venues. Musicians were often untrained, which is another aspect of punk culture: just have a go. Even though no one wants an untrained punk rock surgeon dallying with your interior or an untrained punk rock architect fiddling with your exterior, punk is an exercise in fulfilling your ambitions.

Vivienne Westwood was not trained as a fashion designer, but became perhaps the world’s most innovative and respected in her field. She embodied the punk ethos of “to thine own self be true”, perhaps the prevailing motto that sums all this up, with the codicil that this should be followed no matter the cost. As she told me in later life of her campaigns against fracking and climate change, “I just have to do it, Chris; I have no other option.”

The non-comformist, anti-establishment, anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian ethos espoused by Westwood, McLaren and their contemporaries might have found its moment in 1976, but it emerged well before the 20th century. For some, the attitude is more natural than waking up and history is filled with malcontents causing outrage, shaking the hive. To those who remember the way in which the Pistols and Clash scandalised the country, some of the behaviour will sound very familiar.

The earliest recorded punk rocker may well have been Athenian philosopher Socrates (470–399 BC), who, with his rejection of materialism and his barefoot beggar style, believed in constant questioning of values and beliefs. Charged with corrupting youth, he was ultimately executed for his blasphemous rejection of the gods of Athens.

The equally unshod Diogenes (c. 413/403–c. 324/321 BC) lived in an empty wine vat, begged for a living, adored farting and advised the rejection of luxury, and the absolute denial of “conventional” laws. He was prone to publicity stunts, often masturbating enthusiastically in public.

He loathed Plato, the pampered rock star of their day, and when Alexander the Great asked him why he was looking intently at a pile of human bones, he replied, “I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave.” That is a punk statement.

The pirates had proto-punk credentials too. Historically, those of a punk nature often band together as a means of self-protection and the 17th and 18th century buccaneers, or Brethren of the Coast, were a multinational and outrageously attired seafaring gang who originally fought Spanish persecution. Their ranks included former African and Irish slaves, indigenous Caribs, British political refugees fleeing Cromwell, and press-ganged sailors.

Blackbeard, aka Edward Teach, would attach lighted fuses to his dreadlocks, smear black gunpowder around his eyes, and attack with a pistol in each hand, roaring obscenities in order to scare the opposition into surrendering peacefully.

Womanising swordsmen and brawlers Charles Vane and Stede Bonnet were as camp as a row of tents and mocked upper-class effeminate English fops by wearing plundered silks, satins, velvet, and lace, high-heeled shoes, powdered wigs, rouge, lipstick, and long hoop earrings.

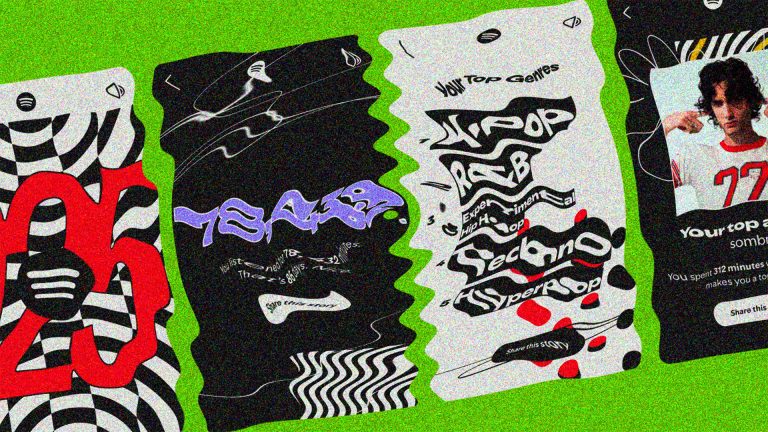

Suggested Reading

Please shut up about your Spotify Wrapped

They established a loose confederacy of rogues, all residing in their “pirate republic” in Nassau, Bahamas, replete with their own codes of conduct known as the Articles of Agreement, involving the democratic voting of a captain, equal sharing of plunder, and insurance for the maimed. Then we have Anne Bonny and Mary Read, who passed as men and pirated alongside the likes of Vane and Calico Jack Rackham, only revealed as women after staging an utterly remarkable pistol and cutlass fight against the Royal Navy in Negril, Jamaica, on October 20, 1720.

When Bonny, who was reprieved, made a last visit to Rackham on his way to the gallows, she told him: “If you had fought like a man, you would not now be hanged as a dog” – another punk statement.

Yet in history as now, the punk spirit was most apparent in the creative arts. Maverick painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) made no sketches and painted straight to canvas, using male and female prostitutes as models to depict Jesus, Mary, and their gang. A bisexual mad drinker and street brawler, he fled Milan after wounding a policeman and arrived in Rome penniless, but was soon regarded as the finest artist in Rome.

Caravaggio spent a year in prison in 1600 for assault, followed by several short stays back behind bars, and on May 29, 1606, he killed an influential pimp and gangster and was sentenced to beheading. Fleeing, he became a Knight Templar in Malta, was arrested for seriously wounding a nobleman, and ran away again with a price on his head. He died in 1610, aged 39, of either syphilis or malaria.

The French realist painter Gustave Courbet, who controversially depicted working people during the French peasant-worker uprising of 1848, painted lesbians, prostitutes, and close-ups of hairy vaginas, and loudly declared that anyone could be a painter, regardless of skill or training. A socialist, he campaigned to abolish child labour, advocated for women’s rights, and helped destroy the Vendôme column, for which he was imprisoned.

He died as a result of his addiction to the mind-altering absinthe, a substance that plagued many a 19th-century punk, whether they be artists like Van Gogh, Gauguin, or Lautrec, or writers like Baudelaire, Wilde, Émile Zola, or Guy de Maupassant.

The enfant terrible of 19th-century French poetry, Arthur Rimbaud, is probably the most direct influence on punk rock of those mentioned so far. With his spiky, unkempt hairstyle and street urchin style, at age 18 he revolutionised poetry while lambasting the pillars of French literary society. He was often described as drunk, arrogant, rude, and foul-mouthed.

Then, at age 21, he abandoned writing and roamed through Europe, Africa, and the Dutch East Indies, working as a mercenary, gun-runner, circus employee, day labourer, and finally an agent for a coffee trader. The Beat poets such as Kerouac and Burroughs, who crafted the punk blueprint for hippie and punk, adored the man, while Patti Smith regularly declared her undying love for him.

No list of proto-punks is complete without that great Dada artist, Marcel Duchamp (whose alter ego was Rose Sélavy, replete with cloche hat, bobbed wig, full make-up, and flapper’s dress). He embraced anarchy, subversion, and provocation. In 1919, he exhibited a porcelain urinal, and in 1920, he had his patrons enter his exhibition through a toilet that stank of urine, only to be greeted by a young girl in a full communion dress reciting obscene verse. So punk rock.

Later in life, Duchamp gave his endorsement to Andy Warhol’s Factory. Another great arch proto-punk rocker who defied categorisation, Warhol was a curiously introverted, twitchy, blotchy, skinny, gay geek with thick spectacles and thinning hair. He arrived in Manhattan alone, frequented the same Village gay bars as William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, and, inspired by UK pop artists such as Richard Hamilton, produced screen prints of Coca-Cola cans in 1961, and then the truly iconic Campbell’s soup can series.

Warhol was the polar opposite of the then-popular hard-drinking, macho painters known as the Abstract Expressionists, whose wild, expressive style was hailed as a raw burst of human spirit and emotion. Warhol’s silk screens were cool, flat, and impersonal, and he maintained that anyone could do them.

“Andy used to say, ‘if you want to be in a band, just do it, regardless of whether you can play an instrument,’” recalled Warhol photographer Leee Black Childers. In January 1977, the fanzine Sideburns encapsulated that feeling in the now-famous drawing of three guitar chord shapes, with the caption “this is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band”.

Punk to the last, none of the above wavered in their unfaltering duty to have their say and do their thing as they saw it. All were ridiculed, physically attacked, maligned by the authorities, made into outcasts. But they lit fires that are still burning.

Chris Sullivan and Stephen Colegrave’s book Punk : The Last Word is published by Omnibus Press, £30.

Chris Sullivan is a writer, painter and DJ