In 1961, the French American artist Niki de Saint Phalle picked up a rifle, took aim at one of her paintings and shot it. Bags of paint embedded under plaster on the painting’s surface dramatically exploded, bleeding reams of colour over the canvas. It would later be remembered as one of her infamous tirs (French for “shootings”).

With this iconoclastic attack on artistic and social traditions, de Saint Phalle said she was announcing the “death of painting” and the destruction of, among other things, “society, church, the convent, school, my family, my mother, all men, Papa, myself, men.” The act may have been very much of its time, but recovering from a repressive upbringing and a deeply traumatic spell of psychiatric treatment, making art was de Saint Phalle’s deliverance from suffering.

Born in 1930, like many of her generation, she was steeped in the dystopian anxieties of the machine age and the atomic era, and found kindred spirits in the contemporary artists who subscribed to the Nouveau-Realisme art movement founded by art critic Pierre Restany in 1960. Their manifesto called for art that fused with everyday life, and the incorporation of found and mass-produced objects (and even detritus) that were direct reflections of the reality of the world they inhabited.

Niki de Saint Phalle was the only woman in the group, alongside fellow artists Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely. The latter became her lover, husband and creative collaborator.

Like de Saint Phalle, Tinguely also embraced the act of destruction as a generative artistic force. He targeted the establishment totems of contemporary society, as well as encroaching modern technology and mass production, often with self-destructing sculptures (such as a giant golden phallus that exploded in fireworks one night in Milan in 1970).

His lifelong preoccupation with creating machines and mechanisms, often ones that were operated in some degree by the spectator, questioned established ideas about creative agency and authority and the relationship with technology that remain piquantly pertinent. One such example is MétaMatic Nr 17, a mobile drawing machine exhibited at the first Paris Art Biennale in 1959 that danced, made noises and spat out ink drawings.

This year marks the centenary of Tinguely’s birth and a spate of international shows to celebrate him. Among these is Myths and Machines at Hauser and Wirth Somerset, which brings together de Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s playful worlds and the fruits of their enduring creative collaboration. A similar exhibition is on show at the Grand Palais in Paris this summer.

The pair met in Paris in the 1950s and were married in 1971, each one devoting themselves to the preservation of the other’s artwork, even if their romantic relationship had by then expired. While nothing explodes in this show, there are plenty of things that move.

A myriad of Tinguely’s bizarre, motorised sculptures periodically kindle into life, amalgamations of animal skulls, scrap metal, chains and found objects. “Tinguely’s machines embody aspects of fragility and strength, and have no other purpose than to be,” says Bloum Cardenas, de Saint Phalle’s granddaughter.

Despite both artists’ preoccupation with destruction and nihilism, the keynote in this exhibition is joy, and not despair. On arrival at the Bruton gallery, visitors are confronted with three sculpted giant female figures who seem to be mid-bound across the lawn; pneumatic, chromatic, and voluptuously joyful in the glinting sunshine.

The works, known as Les Trois Graces, are examples of de Saint Phalle’s Nanas – her serial motif and ode to the female form. In their daringly monumental scale, bright colours and unapologetic curves, they were a feminist reinvention of stereotypes of female bodies that had hitherto populated western art and myth.

The Nanas (the French translation is a mildly salacious term for girl) take up space throughout the gallery. One stands statuesque and impervious with green handbag and red shoes, wearing a breastplate like a giant bloodshot eye. Another is found ice-skating with reckless joie de vivre. Elsewhere, they appear in smaller form, like cake toppers on top of Tinguely’s mechanised motors.

Suggested Reading

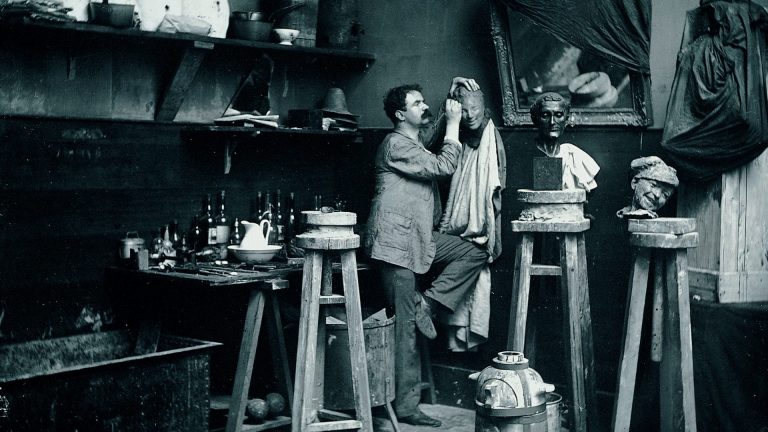

The forgotten, formidable Medardo Rosso

Together, the pair worked on a number of monumental sculpture projects and film projects – archival photographs and examples of which are on display. These include Le Cyclop, a gargantuan mechanical sculpture of a head made from tons of scrap metal and encrusted with mirror mosaic which the pair constructed with the help of a crew of numerous artists on a plot of land among the trees in Milly-la Forêt, a commune outside of Paris.

Tinguely, who self-funded the project, saw it as a utopian ideal of making art away from the commercialism, egotism and bureaucracy of the art market. The pair shot the 1976 film Un reve plus long que la nuit on site, de Saint Phalle’s fairytale ballad of a daughter’s transition from childhood to adulthood, populated with Tinguely’s machines and de Saint Phalle’s décor, some of which are on show.

De Saint Phalle became smitten with the esoteric via the influence of Tinguely’s first wife, artist Eva Aeppli, who introduced her to the symbolism of the Tarot deck. This led to the designs for the Tarot Garden in Capalbio in Tuscany, a sculpture park filled with 22 sculptures inspired by the Tarot major arcana on which Tinguely and de Saint Phalle collaborated between 1979-1998. (The garden is open to the public each year between April and October.)

Among the works is the Empress, a giant inhabitable sphinx sculpture that de Saint Phalle lived in as if she were a mythic goddess. “She didn’t want to owe anything to anyone and wanted to be totally independent for how she chose to live,” says her granddaughter.

Tinguely and de Saint Phalle’s was a complicated love story. It included 10 years of an open relationship and was characterised above all by a vivid competitiveness in their lovemaking as well as their artmaking. “They were like magicians,” Cardenas says. “They would be talking about something one day and a few days later it became reality.”

Myths and Machines is at Hauser and Wirth Somerset, Bruton, until February 1, 2026