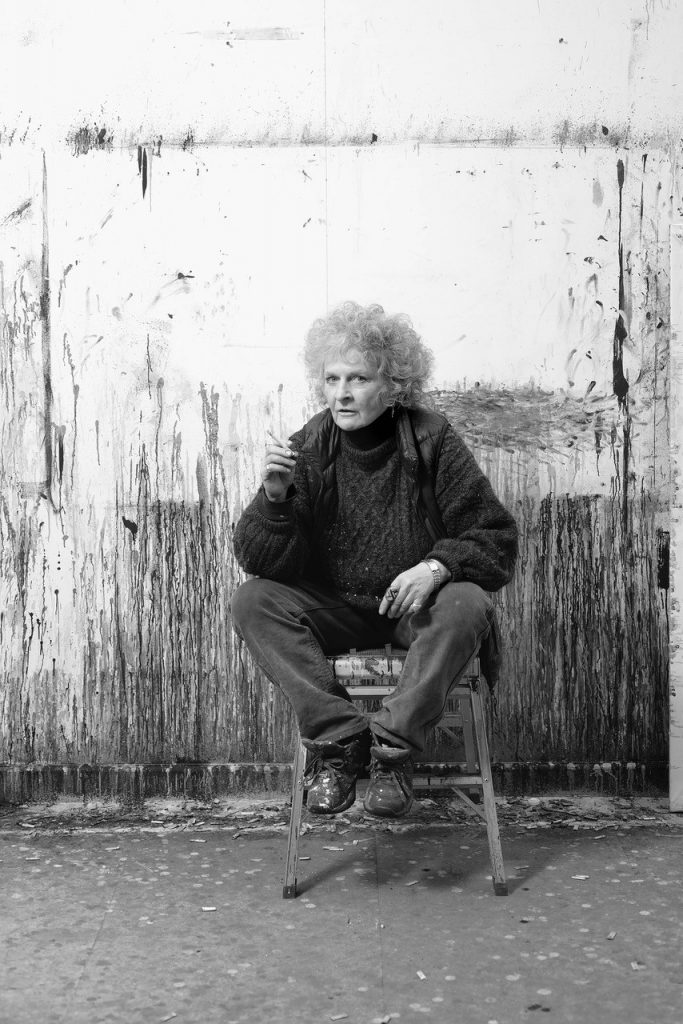

When Maggi Hambling was a toddler, she used to talk to the sea. “I lectured it as if it were my best friend, but now as I’m a bit older, I try to listen to it,” the notoriously mischievous artist, now approaching 80, tells me.

We’re at Wolterton Hall, a Palladian stately home in Norfolk that was the family seat of Horace Walpole, ambassador to France and the younger brother of Robert Walpole, who is regarded as Britain’s de facto first prime minister. Beyond the windows, a 10-acre lake reflects the passing clouds, and a medley of moorhens, the occasional kingfisher and hare darting by. Inside, contemporary art offsets tapestries and the odd Gainsborough portrait.

Once a Whig powerhouse of Norfolk, playing host to Lord Nelson, the Ellis family bought the historic home in 2023 and have opened it to the public with a growing programme of cultural events. Hambling, now 79, is here to celebrate the installation of Sea State, Wolterton Hall’s inaugural exhibition under its new stewardship. The exhibition, co-curated by artistic director Simon Oldfield and curator Gemma Rolls-Bentley, places Hambling’s paintings alongside works by British sculptor Ro Robertson in the hall’s historic interiors.

Once home to masterpieces such as Rubens’s Rainbow Landscape, the entirety of the original art collection was sold off at Christie’s in 1856, with “everything from the Rubens to the bedpans” lost to the market in a blind sale, according to Will Ellis, who is managing the hall’s archive. The family now plans to develop a new art collection that bridges contemporary with historical works. Last year, Thomas Gainsborough’s sultry portrait of recently widowed Maria Walpole (the illegitimate daughter of Edward Walpole), was acquired, while Robertson’s and Hambling’s works for Sea State represent the first contemporary additions.

The sea has been a meaningful subject for both artists. Growing up in Suffolk, Hambling habitually studied the waves of the coastline, but describes witnessing a storm devastate the beach at Southwold in 2015 as the turning point that prompted her ongoing body of work, Wall of Water. “It’s a very polite place, and these great waves crashing down on the pathetic little man-made sea wall seemed like nature answering back to all the destruction we’re doing,” she says.

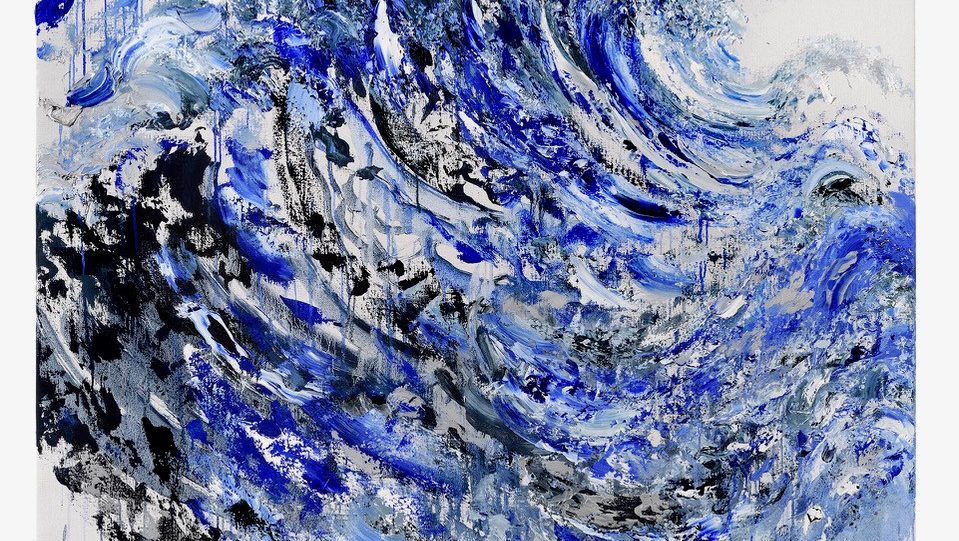

Two new works in the series are unveiled in the exhibition, both pulsating with impasto oil paint that drips across the 1.5m-high canvases in roiling brushstrokes of blues, blacks, yellows and white. The artist speaks with animation about the East Anglian waters: “People think the North Sea is grey, but they’re quite wrong. It’s iridescent, sometimes turquoise, sometimes bronze, it’s silver. It’s changing all the time. I see the sea as a great mouth eating the shingle, the sea just does what it wants.”

Hambling’s walls of water speak to a long art historical tradition of picturing the tumult and majesty of the sea and the feelings of insignificance it inspires. But this exhibition also speaks to other far less visible subjects and experiences than depictions of indifferent, sublime nature.

Hambling produced a 40-strong suite of paintings of waves in a few feverish days after her partner, the artist Tory Lawrence, passed away in 2024 after a 40-year relationship. Each one unique, they are diminutive in scale but compressed with energy.

Placed in a line around the bare walls of the stripped former Portrait Room at Wolterton, they make something of an alternative poetic portrait of Hambling’s deceased love, as if she herself had become one with the eternally moving water. At the centre is a serene depiction of Lawrence, her features loosening in fluid contours, a watery halo trailing above her head. It is a poignant depiction of love and grief.

As Rolls-Bentley points out, “these are stories that do not normally appear in settings like Wolterton Hall,” referring to the historic invisibility of queer joy and love in the nation’s historic stately homes. (A former denizen of late-night Soho, Hambling has long identified herself with the self-coined term “lesbionic”).

Rolls-Bentley is right, but Hambling is not keen to dwell on pathos or politics, and regularly brings the conversation back to bawdy and saucy asides. Everything is “sexy” to her: oil paint, the sea, waves a metaphor for orgasmic release. I ask her thoughts about British identity and the sea, and she answers, “Most people’s idea of a nice time is a day at the seaside, it’s always been a place of leisure as well as somewhere people go for the dirty postcards”.

Sunderland-born sculptor Ro Robertson (b.1984) speaks more quietly of their work, while acknowledging the huge influence Hambling had on them as a young, queer artist. Swell, a two-metre-high, elegantly welded steel structure with openings and hollows, sits in the middle of the Marble Room, flanked by colourful works on paper on the walls.

“They’re of the sea, but not seascapes,” the artist explains, detailing the way in which the colours and textures are inspired by feelings and sensations, such as the sun drying the skin after being in water for the first outdoor swim of the year.

Robertson was inspired by how nature reclaimed the River Wear of their home town of Sunderland, a landscape choked by the region’s industrial history. At a time when the artist was searching for a template to navigate their own identity, the river’s course to the sea provided a map to follow and a place of welcome fluidity, undefined by boundaries.

Boundaries, by contrast, have been the prevailing motif of our recent political paradigm, the waters around the British Isles a contested territory enmeshed by market forces, embittered fishing rights negotiations and the policing of migrant and refugee boats.

Hambling’s desire to listen now to the sea she once lectured as a child is perhaps symptomatic of a broader cultural moment in which we are being forced to reckon with forces beyond our control. Ultimately, water serves as both metaphor and medium for the stories that Sea State seeks to tell – tales of love and loss, of boundaries dissolved and histories recovered.

Sea State, an exhibition by Maggi Hambling and Ro Robertson, is at Wolterton, Norfolk, until December 7

Catherine McCormack is an art historian, author, and critic