Walking down the wine aisle, “I’m all lost in the supermarket” by The Clash may as well be playing. You’ll see gold medals gleaming on wine bottles, and medals incorporated into the design of wine labels. It’s all suggestive of a certain quality, with medals or similar symbols acting as heuristic incentives for the unassuming wine drinker. But appearances can be deceptive.

At my local Tesco, I’m drawn to the Decanter gold medal on a bottle of the Italian red Memoro. Also sold at Asda and Sainsbury’s, Memoro is among Britain’s most popular reds, selling around four million bottles in the UK each year, according to its producer, Piccini.

The year on the medal is 2019, which I first think is the vintage, the year of production, but, confusingly, it turns out that 2019 is the year the wine won the gold medal. More startling is the fact that Memoro is a non-vintage wine: every year, Piccini makes new blends of the wine but uses the same gold medal from 2019 on its bottles. In other words, the Memoro wine you are drinking is not the same wine that was awarded the gold medal six years ago.

The medal is meaningless. I’ve been fooled and misled. No information is provided in supermarkets as to what the medals mean. What’s more, tasting the wine, I’m left feeling flat; rather than evolving, within 30 minutes the wine’s initial inviting aromas and flavours dissipate.

Antonio Ciccarelli, marketing director at Piccini, exuberantly compares having a Decanter gold medal for a non-vintage wine to a “lifetime achievement award”. He points out that were he to re-enter the wine to competition each year, he’d risk not obtaining a gold medal. That’s true… but it’s consumers, blinded by gold stickers, who are losing out.

Onto Asda’s wine aisle, where placards boast: “We’re the most-awarded supermarket for wine” in 2025. Ironically, and again, confusingly for the consumer, more prominent than medal stickers on bottles is the gold logo of Asda’s own ‘Exceptional’ range, which clearly resembles a medal. However, for clarity, this is not the “Exceptional” awarded by Decanter for wines that achieve 98-100 in its scoring system!

When challenged on the lack of information, or the misleading nature of medals, wine competition directors, judges and retailers invariably suggest that consumers can go to their websites and social media for information.

Yet, in doing so, astonishingly, I discover that anyone can buy the London Wine Competition’s (LWC) gold medals. On its website, I purchase a thousand gold stickers from the 2024 LWC competition, priced at £50; during the purchasing process, I am not asked whether I entered any wines to the competition, or if I had any awarded wines.

I receive the medal stickers in the post within days, with my invoice from LWC’s US owner, Beverage Trade LLC, based in Wilmington, North Carolina. Should I so wish, I could put them on any bottles.

The French-owned company Armonia, which this year launched the London Tasting Awards, says that it has recently been involved in legal disputes with wine companies in France and Germany, over the use and abuse of medal stickers. “It has happened. It is impossible to control everything in every market,” says Lucille Oudard, director of the London Tasting Awards (LTA) and Armonia UK Ltd.

Armonia runs 15 wine competitions, including Concours International de Lyon, Concours des Grands Vins du Beaujolais and the Frankfurt Wine Trophy. France, Europe’s epicentre of wine judging with 124 officially recognised wine competitions, has the most stringent (or for some competitions, restrictive) regulations on wine competitions; ironically, however, it’s also the country where recent fraud cases have involved the misuse of wine medals on bottles.

In one prominent recent fraud case, whistleblower Ludivine Jeanmingin, former manager of Champagne house Chopin, revealed how her former boss Didier Chopin placed gold medals awarded by the International Challenge Gilbert & Gaillard (G&G) wines on bottles of fake Champagne. “Using medals was an important tool for entering export markets,” Jeanmingin said.

On September 2, 2025, a judge in Reims sentenced Chopin to four years’ imprisonment (18 months in jail, with a further suspended sentence of 2.5 years) in a case involving the production of up to 1.8 million bottles of fake Champagne.

Found guilty of fraud and misappropriation of an appellation, Chopin and his wife, Karine, who received a two-year suspended sentence, were fined €100,000 each, with his company ordered to pay €300,000.

In another prominent fraud case, in February 2025, a Bordeaux court fined Ginestet, a prominent Bordeaux wine merchant, €100,000 for committing consumer fraud. Ginestet sent 250,000 wine bottles to Japan with G&G stickers stating that Ginestet wines had won 66 medals; the wines sent to Japan had not won any medals.

The new London Tasting Awards (LTA) has come under scrutiny, after over two-thirds of medals awarded were gold medals (139). In its first edition, held in April this year, LTA awarded 201 silver and gold medals to more than half of its 400 wine entries. Armonia would be unable to award so many medals in its wine competitions held in France, where regulations stipulate that only 33% of wine entries can win medals.

Suggested Reading

Come and see the best fountain in the world

Director Lucille Oudard says LTA guarantees the quality of wines by only giving awards to wines that score at least 75 points out of 100. However, she admits that more could be done to communicate what’s behind each medal. “It’s important to be honest about the competition process, so that consumers know what they’re buying.”

While an increase in wine competitions in the past decade has fuelled competition over securing wine entries, several wine competitions have reported a drop in participants. Consequently, they are under pressure to attract a greater number of wine entries by awarding gold medals.

Christine Guibert, CEO of IWSC (International Wine and Spirits Company), owned by the US Conversion Group, says she refused to allow a partner company in the US to upgrade IWSC medals in the US market from silver to gold, as this would jeopardise the company’s reputation.

A managing director of a prominent international wine competition based in London said its company’s US shareholders had demanded an increase in the number of gold medals awarded to ramp up sales, but the director refused to do so, on grounds of integrity. “My judges would not agree to this, and would leave the competition,” the director said.

Despite the rise of digital marketing, medal sticker sales remain a key source of income for lucrative wine competitions, which have flourished over the past decade, in Europe and beyond.

The IWSC says its medal sales have not fallen. Vienna Wine Competition says medals represent 10% of turnover, yet for France’s Armonia, medal sales account for almost half of the company’s turnover.

Antonio Ciccarelli, director of Piccini, said having a gold Decanter medal was fundamental in getting the Memoro wine into the market, pointing out that only gold medals help sales.

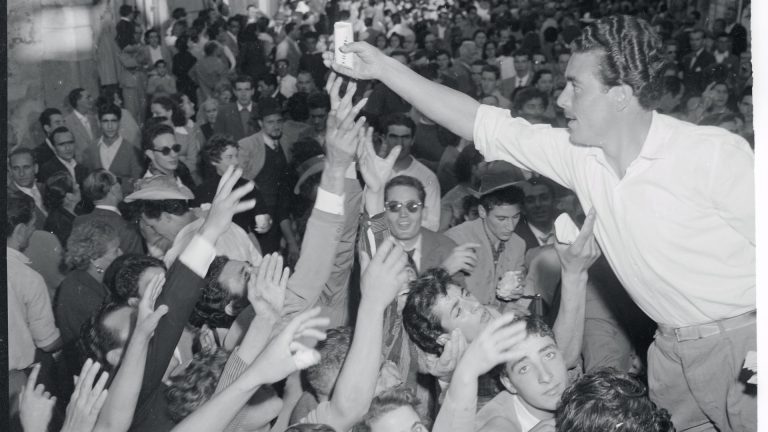

Sting operations against the Gilbert & Gaillard wine competition by Patti Chiari, a TV programme produced by Swiss public broadcaster RSI, and Belgian TV show, On N’est Pas des Pigeons, have raised questions about how a corrosive commercial imperative may impact judging procedures in competitions. It both cases, cheap wines rebranded with fictitious labels obtained gold medals.

Christelle Guibert, a former tastings director at Decanter, has revealed that when she worked for Decanter, producers would provide incorrect prices for wines – the incorrect prices were passed on to judges. “We could not check them [the prices], because there were too many entries,” she said.

Decanter World Wine Awards wines are judged under three price bands, with most wine entries winning medals. Most wine competitions do not reveal the wine prices to judges, when they blind-taste wines, as prices may sway judgement.

“Until I have a system that guarantees that wine prices that I give to judges are correct, I am not going to integrate pricing into the IWSC wine competition,” she said.

Meanwhile, Oudard says the London Tasting Awards has brought a new approach to competitions in the UK, by ensuring that wine panels are formed of both professional wine judges and amateur tasters, who may be more in tune with what wine drinkers like – they may also have conflicting opinions about a wine.

Wine competitions can be lucrative. CMB (Concours Mondial de Bruxelles), for instance, generated an annual turnover of €2 million in 2024, and net profits of €200,000 from inscription fees, shipping costs to enter wines, and from the sales of medal stickers and other promotional activities. Wine competitions including CMB, the IWSC, and the Frankfurt Wine Trophy have become global, with host countries footing their costs.

China is alleged to have paid €2.5 million to host this year’s main CMB wine competition in May. Wine competitions, however, deny that host countries influence the outcome of wine competition results.

Yet, the self-perpetuating system of B2B relationships between producers, buyers, sellers, pundits and judges feels all rather too cosy. This would explain why wine competitions are so popular with wine companies, who use medals as a marketing tool while leaving consumers in the dark as to what they mean, or how effective checks on awarded wines are.

Such competitions have largely failed to attract a new generation of natural wine producers, who prefer customer recommendations, says Doug Wregg, director of the London-based Les Caves de Pyrene, a distributor of fine natural, organic and biodynamic wines.“I guess it is meaningful for some to be judged against one’s peers, but I think the idea of competitions is ridiculous,” he said. “They are mere snapshots of how a wine is showing, also biased towards who can afford to enter their wines into competition and susceptible to competition ‘groupthink’”.

But to many time-poor and inexperienced wine buyers, the shiny allure of a medal remains an instantly recognisable mark of supposed quality. And so the medals will go on and on.