Writing for The New World in December, noting US pressure on Venezuela and the US National Security Strategy’s “Enlist and Expand” policy, I stated that in 2026 we would see the lengths to which America will go to expand its presence within its sphere of influence – particularly with states aligned with strategic competitors.

We did not have to wait long.

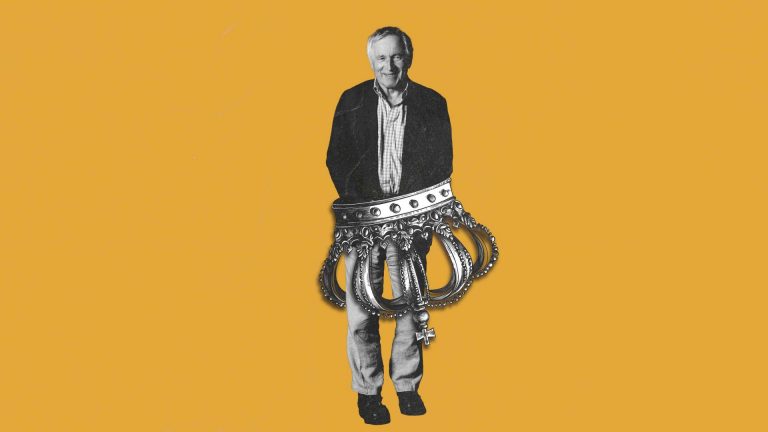

In a special military operation that would have caused much jealousy in Moscow, American tier one special forces successfully captured Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, hours after he had met with a delegation from China, and flew him to the US to face drug charges. Maduro had ruled since 2013, when he was the chosen successor of Hugo Chávez who had led the country from 1999.

His removal is a seismic moment from the country that has endured over 30 years of populist economic policies, some of the highest levels of violent crime in the world and social fragmentation. It is also a country that has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. which Donald Trump claims US firms will now help exploit creating “oil prosperity” for the US.

Chávez claimed his political ideology (known as Chavismo and followed by Maduro), was not Marxist nor socialist but strongly shaped by both. He was heavily influenced by 19th-century independence leader Simón Bolívar, whose philosophy was a mix of pan-Hispanic, socialist and nationalist-patriotic ideals. Over the years Chavismo became increasingly authoritarian.

After rising oil prices in the early 2000s, spilled money into Chávez’s treasury, he created the Bolivarian Missions to provide public services to improve conditions for Venezuela’s poorest. Aid, however, was distributed to only some of the poor; those who supported the regime. It was used to maintain power rather than alleviate poverty.

It involved the creation of the colectivos, loyal militias that would do the government’s bidding and could be trusted more than the educated officer class in the military, to enforce the government’s will. In the barrios – the low income neighbourhoods in Venezuelan cities – colectivos would exchange security and basic services for regime loyalty.

Successful businesses that did not align with the regime were nationalised, and often then run into the ground for short term profits. Maduro’s government withheld US dollars from importers and price controls were put in place due to scarcity of basic goods. US sanctions further squeezed the economy.

All this resulted in an unprecedented “brain drain’ of middle class educated Venezuelans. As cited by the US government, it also resulted in the emigration of criminal gangs looking for loot elsewhere. The news of Maduro’s capture has been welcomed in Miami, home to a large proportion of the Venezuelan diaspora.

Suggested Reading

The beginning of the end for Donald Trump?

I have seen first-hand the poverty of the barrios that hug the hillsides around Caracas. The dense, colourful, makeshift housing that creates vibrant mazes, connected by the informal infrastructure of wires and pipes that look like whimsical yet precarious contraptions drawn by Heath Robinson, and punctuated by marketplaces, murals of Chávez and Che Guevara, and basketball courts.

The most famous is the intimidating concrete monoliths of the January 23 barrios (the date of the 1958 coup d’état), perched high on a hillside, the heart of Chavismo in Caracas. In a more affluent neighbourhood in central Caracas, I had lunch with my hosts at a restaurant where there were no prices on the menu as they changed so regularly due to hyper-inflation.

My hosts were happy to socialise over lunch, but would not do so in the evening fearing travelling home in the dark. In all districts of Caracas there is now uncertainty and fear about what will come next.

I have also seen first-hand the unintended chaotic consequences of regime change after a long-ruling, highly repressive regime falls through outside intervention. Yet, Venezuela is not Iraq. With Venezuela there is an opposition that has been planning for this moment for years.

The US did not recognise Maduro as president, instead naming Edmundo González as the winner of the 2024 election. The country’s official results claimed Maduro as the winner, although they presented no evidence to support this claim. González’s supporters were able to present significant evidence that he had won.

International monitors called the elections neither free nor fair, citing Maduro’s control of most institutions and opposition repression. Yet González was forced to flee to Spain.

There is also last year’s Nobel peace prize winner, María Corina Machado. Machado won the 2023 opposition primary to become the unity candidate for the 2024 election, but was barred from running. The Nobel committee called her “a key, unifying figure in a political opposition that was once deeply divided”. However, El País described Machado as being part of the “most radical wing of the right”, whose views on social media are defended by the national right “MAGAzuelans”.

At the time of writing neither are in the country. They will have plans and supporters in the country to execute those plans.. The high court has named vice-president Delcy Rodríguez interim president to “guarantee administrative continuity and the comprehensive defense of the Nation”.

The US has claimed Rodríguez will work with them. In her first cabinet meeting she has suggested she will cooperate.

There are many who have much to lose if the regime falls. There are loyalists in every barrio in every city. They are heavily armed and fearful of reprisals. When opposition coalitions, united in their goal of removing their political foe achieve their goal, the glue that holds them together loses its adhesiveness. There is much yet to be resolved.

This is the most significant US intervention in South America since the 1989 Panama invasion and arrest of General Manuel Noriega on drug charges, an intervention described by the UN as a “flagrant violation of international law”. Panama’s electoral tribunal quickly reinstated the results of the 1989 election that Noriega annulled, confirming the victory of President Guillermo Endara.

Panama’s democracy has survived since. There is no guarantee of a similar scenario in Venezuela.

It is unclear if the US has plans for the next steps, other than vague comments from Donald Trump about running the country until it can be made safe, which is where we return to parallels with Iraq.

The foreign correspondent Robert Kaplan initially supported the Iraq intervention, but came to deeply regret his advocacy.

Suggested Reading

María Corina Machado, the Nobel peace prize’s difficult winner

In his soul-searching, Kaplan turned to the Greek tragedies. There he found the timeless lessons on the complexity of human affairs, the dangers of hubris, the limits of our agency and our ability to understand our fate, and came to understand that tragedy is not the triumph of evil over good, but the suffering caused by the triumph of one good over another or the choice of one evil over another.

Kaplan ultimately urged policymakers to adopt a position of “anxious foresight” to guard against hubris. This recognises the importance of thinking through the worst-case scenario of any policy of action or inaction, the limitations of our knowledge, and the risk of unintended consequences.

The unintended consequences from this could not only create chaos in Venezuela but instability across the region. Colombian president Gutavo Petro has deployed troops to the Venezuela border and called for the UN to “meet immediately”.

It can be true that the US actions are illegal and damaging to global stability and also true that removing Maduro could be good for the majority of Venezuelans. Yet the good, as it was in Iraq, may however be very short-lived and lead to further tragedy.

What is an undeniable reality is that we are now in a world where the country that once upheld international law (despite its own frequent breaches) believes “might is right” within the spheres of influence of regional powers.

Running all the risks that Kaplan found in the Greek tragedies, US military might has affected regime change. We shall now see if lessons from Iraq have been learnt about what needs to come next and what, if any, anxious foresight has been adopted.