The film adaptation of Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, follows the story of the small group of US investors who first recognised that the US subprime mortgage market was heading for disaster. One of the earliest to spot the impending 2008 financial crisis was Michael Burry. The last frame of the film stated that, having correctly predicted the crash, Burry was focused on investing in a single commodity, one that he believed would increase in value because of its increasing scarcity: water.

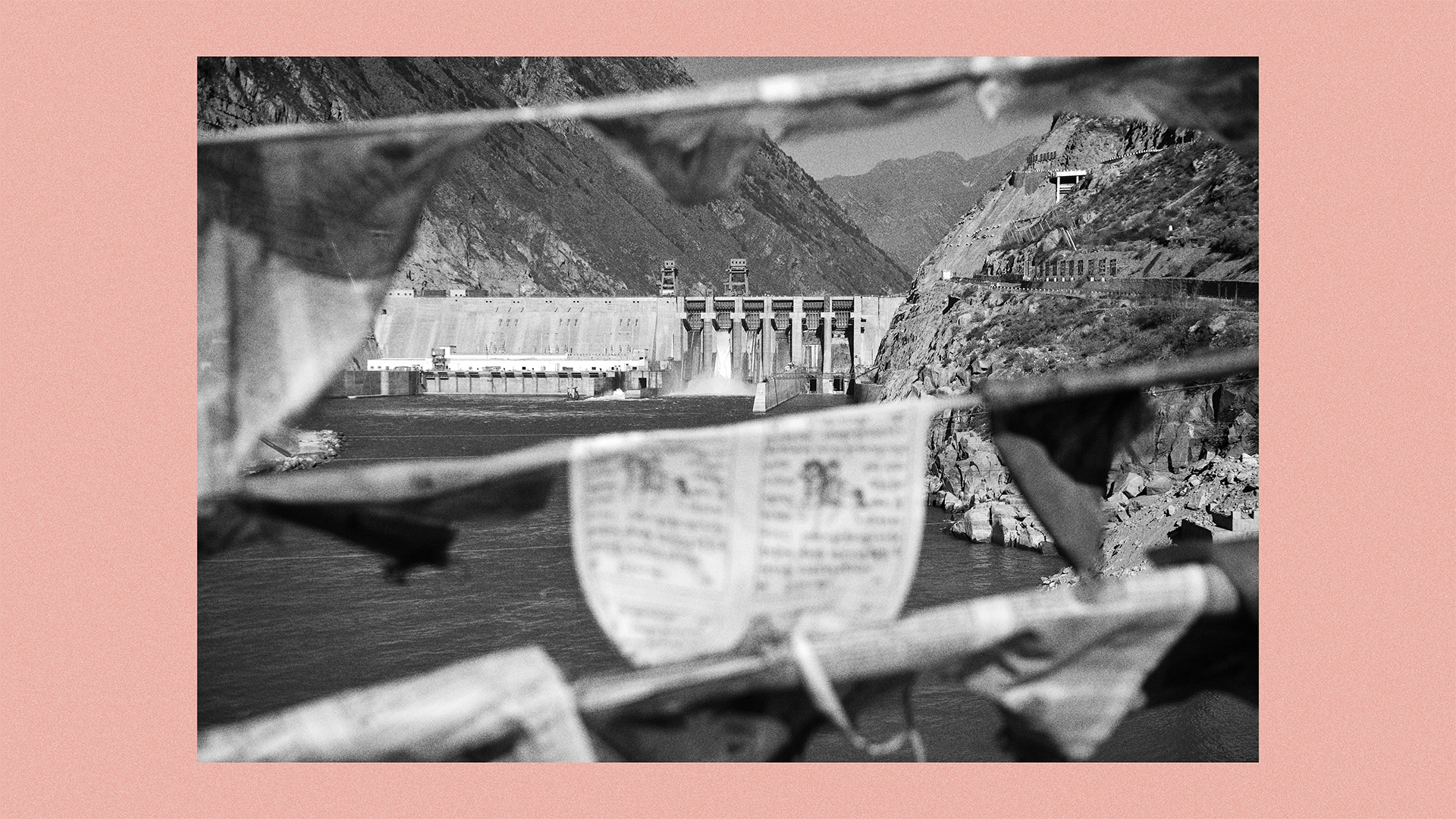

Water is the most important resource of all. It is also a growing source of crisis – and confrontation. The risk of a direct conflict between nations over water is increasing, and that risk became even more acute in July when China began the construction of a series of dams on the Yarlung Tsangpo river, high on the Tibetan plateau. Beijing claims this will be the largest hydropower dam in the world.

The precipitation that falls on the Tibetan plateau and across the Himalayas, along with the meltwater that runs off these highlands, is crucially important for both China and India. The recent interactions of these ancient cultures has been marked by competition, collaboration, trade and war – directly in the Sino-India War in 1962 as well as numerous other border skirmishes, most recently in 2024. And now the two nuclear-armed nations with the two largest militaries in the world are in a profound disagreement over water.

The plan is to construct five dams along a 50km stretch of the Yarlung Zangbo, during which the water drops a total of around 2km. Costing $170bn, it will come on-line in the early‑to‑mid 2030s. The Yarlung Zangbo – the largest river in Tibet – crosses the border into India’s most north-easterly state, Arunachal Pradesh, where it becomes the River Siang. Beijing refers to this part of India as “South Tibet” and claims the entire state as part of China. The river then flows into the Assam valley where it becomes the Brahmaputra and from there continues into Bangladesh.

Both India and Bangladesh rely on the river for irrigation, hydropower and drinking water, and both governments have said that the Chinese dam will cause serious disruption to their water supply. The chief minister of Arunachal Pradesh has said the dam could remove 80% of the river in his state. That claim is contested. A significant amount of the water enters the Brahmaputra from monsoon rainfall that comes south of the Himalayas, and will not be affected by the dam.

The Chinese have said the dam is intended to provide “run of the river” hydropower, meaning the water should flow normally through the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangpo. However, the water governance scholar Sayanangshu Modak has pointed out that, even if that is true, the dam could still give Beijing the capability to cut off the water if it wishes, which itself poses a substantial threat. The Lowy Institute, an Australian think tank, noted that “control over these rivers [on the Tibetan plateau] effectively gives China a chokehold on India’s economy”.

Several key rivers which feed India’s northern plains – including the Indus and Ganges – also originate in Tibet, and many millions of people across Pakistan, India and Bangladesh rely on these waters. Population growth and intensive irrigation on the plains of the subcontinent have already created water shortages leading to regular clashes between villagers. Pakistan has also accused India of weaponising shared water supplies in the disputed territory of Kashmir, after it suspended participation in the Indus Waters Treaty. Water is already a source of intense regional disagreement.

Suggested Reading

The silent threat of China

There is a long history of skirmishes between India and China. In 2022, dozens of Chinese and Indian soldiers were injured after a fight on the eastern border, in Yangtse, where troops attacked one another with nail-studded clubs. Less than a month later there were reports that China was building “structures” in that area that might dam the rivers, restricting their flow into India. A border agreement last October has helped to de-escalate tensions. However, both countries still have 50-60,000 troops deployed in the border area.

At the root of these border and water disputes is the issue of Tibet, which China invaded and annexed in 1951. The Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibet, and remains a focal point for the Tibetan independence movement. Since the Tibetan uprising of 1959 he has been in exile in India, where he remains a target of intense Chinese diplomatic animosity. That uprising was followed by a sequence of diplomatic disagreements and border clashes between China and India which led to the 1962 war, when China invaded disputed territory in both Ladakh in India’s high north, and on the northeastern frontier.

Significantly, the fighting coincided with the Cuban Missile Crisis, during which the US was distracted by the gathering threat of nuclear war. The conflict ended when China unilaterally declared a ceasefire on 20 November 1962, the same day the US lifted the blockade of Cuba, which reflected Chinese concerns over US intervention.

And now the US is distracted again. India has always believed it has been able to call on the US when its interests come under pressure from Beijing. But Trump’s America First worldview puts less emphasis on regional strategic partnerships, unless they benefit the US in the short-term. Trump’s recent pressure on Nerendra Modi, the Indian prime minister, to stop buying cheap Russian oil further complicates the equation. Modi understands that while the US sees India as a bulwark against China and as an influential diplomatic voice, Trump may not be a reliable security partner if there is no direct benefit to the US.

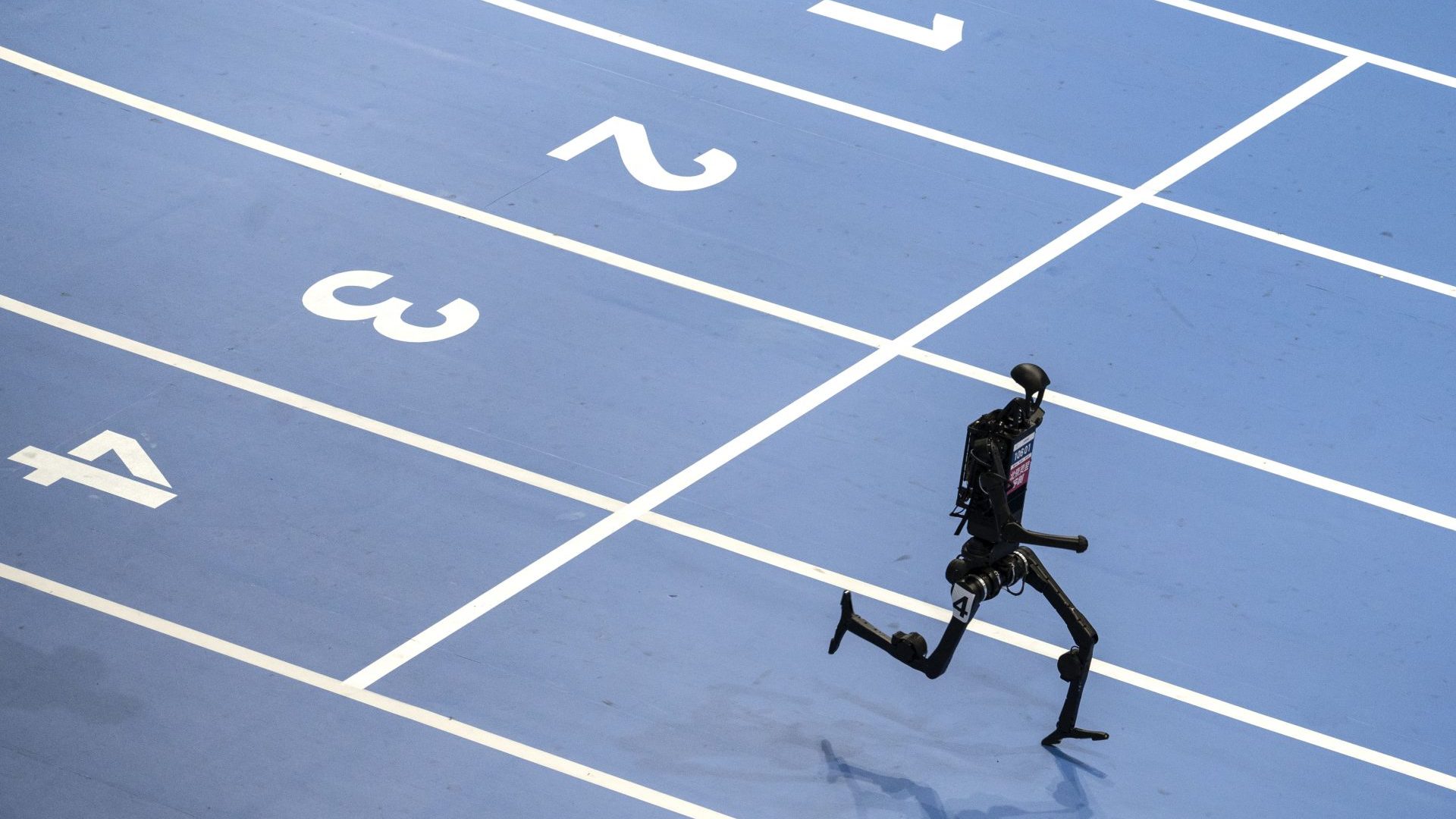

China understands Trump’s disinterest. Since the start of Trump’s second term, China has withdrawn engineers from factories in India and has officially renamed sites in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, both highly provocative moves. Beijing’s support of Pakistan, particularly over the issue of Kashmir, is another source of tension. Eighty-one percent of Pakistani military hardware procured in the last five years has been sourced from China. During the brief conflict in May between India and Pakistan, triggered by a terrorist attack in Kashmir, China reportedly provided Pakistan with live satellite intelligence on Indian deployments. India’s deputy army chief said that China treated the conflict as a “live lab” for its weapons systems.

Chinese support enabled Pakistani forces to perform far better than India expected. The downing of one of India’s newly delivered French Dassault Rafale fighter jets led Pakistani and Chinese sources to proclaim a victory for Chinese technology over western equivalents. Since then, Dassault’s share price has fallen, while Chengdu’s – the manufacturer of the Chinese made aircraft used by Pakistan – has risen.

While Modi views the world as a geopolitical system of “multi-alignment” in which India is a great power among other great powers, China views India as merely a pawn in its competition with the US. China is the only permanent member of the UN Security Council not to endorse India’s candidacy for a permanent seat. In return, India is the only South Asian country not to endorse China’s global infrastructure development strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative.

In February, India announced a record 9.5% rise in its defence budget (although over a quarter of this will go on pensions) which was intended as a signal to Beijing, but Modi also knows that India relies on China for raw materials. The wider economic relationship is far from even: Chinese exports to India now surpass $100bn, while Indian exports to China are just over $15bn. India has limited the level of Chinese investment permitted in strategically important sectors and has banned several Chinese-owned apps, including TikTok. But these restrictions are under constant pressure from Indian business leaders keen on attracting more Chinese investment.

Competition between the two countries is also starting to play out further afield. India is now the second-largest bilateral creditor across the continent of Africa (after China) and the third-largest trade partner (after China and the EU). China is also financing the construction of several dams across Africa.

An increase in the number of dam projects on great rivers at a time of escalating climate change and water scarcity has the potential to create instability – and conflict. That will be the case across Africa; and yet the proposed Yarlung Zangbo dam is perhaps the most worrying example. Neither India nor China currently wants war, yet their armies are large and growing, competition between the two states is intensifying and the number of potential flashpoints is rising.

Suggested Reading

India’s missed opportunity

Cycles of mistrust and military buildup increase the likelihood of war, even if neither side wants it. Modi’s pragmatism means he is currently adopting a policy of appeasement to an increasingly assertive China, favouring economic development over the risk of being perceived as weak domestically.

India and China have slipped into conflict before – but those disagreements were over lines on a map, between two nations that already control vast territories. If the next confrontation is over water, then the lives and living conditions of tens of millions of people across India could be at stake. A conflict that arose in those circumstances would be very different. We must hope it doesn’t come to that.