The American mathematician Edward Lorenz was using a computer simulation to explore weather patterns. He ran a sequence of data again. Saving time, he started from the middle of its run, but using data rounded off to three decimal places, rather than the six originally used.

This created a radically different outcome. In complex systems, tiny differences in initial conditions can lead to big differences in long-term outcomes. Lorenz noted, “the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.”

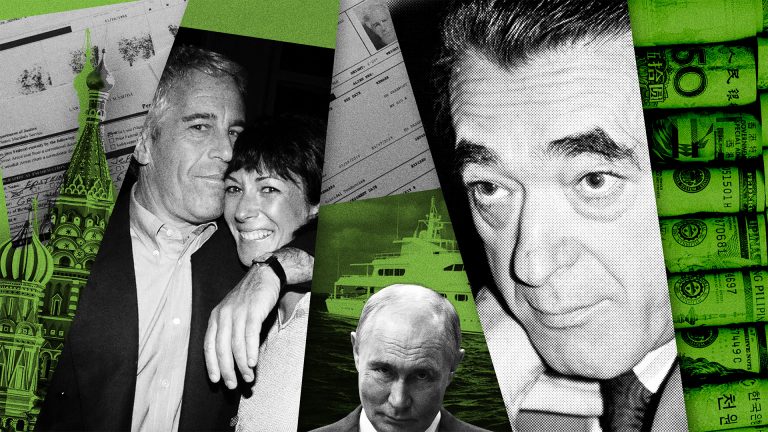

As the post-1945 international system fragments, our understanding of the chaotic present is becoming more approximate. The news that Europe has finally agreed a multi-billion euro support loan to Ukraine gives some shape to its current war against Russia. But the war itself shows no sign of ending – more than ever, we look ahead and see a period of deep global uncertainty.

The Middle East

The region is a microcosm of the present problem: new norms of violence have been established in which a regional power – Israel – asserts its military might in what it believes to be its sphere of influence, regardless of international law. The realities of power have trumped calls for justice.

In Gaza, the composition of the International Stabilisation Force (a job no-one wants while Hamas remains armed), and the “technocratic, apolitical Palestinian committee” remains unclear. The Palestinian Authority’s reform program is also yet to be completed. In the meantime, ordinary Gazans are denied any possible sovereign future.

Internal politics in Iran, where the aging Ayatollah struggles to provide basic necessities in an ailing economy, and Israel, where Netanyahu attempts to evade his fraud case and stand for election again, will influence the region’s future.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah is rearming and will be seen as a threat by Israel again. Syria will teeter, as old grievances start new cycles of violence. Simultaneously, November’s US National Security Strategy (NSS) signalled a desire to untangle America from security matters in the region and to focus instead on economic relationships with opulent Gulf States.

Suggested Reading

Trump goes to war

While some are making calculated decisions, balancing security, economic gain and international condemnation, others are operating by the logic of rage and revenge. The grief of a thousand tragedies led to the rage behind the vengeful violence of October 7. The resulting grief led to more rage, and, as America was driven by lust for revenge into its global war on terror, Israel has been driven into wars with similar chimeric goals.

It remains unclear if the new norms will create a new regional equilibrium or a self-aggravating cycle, which continues to spiral. The West faced retaliation for its ill-judged post-9/11 wars. In 2026, more tragedy seems likely to unfold.

Ukraine

It’s easier to forecast what we will not witness in Ukraine in 2026, and that is justice. Russia launched an unjust war of aggression and has used unjust means to fight it. In all possible scenarios for peace, none contain justice.

Putin, however, has no interest in any scenario that secures Ukraine’s long-term sovereignty and will string president Trump along while continuing his meat grinder tactics on the battlefield and drone swarm tactics against Ukraine’s cities. Ironically, Trump is likely to lose patience with president Zelensky before Putin. Ukraine’s new loan from European countries suggests Kyiv will now go ahead without US support.

Suggested Reading

We are Putin’s next target

Putin will need to appease a growing army of physically and psychologically scared veterans, grieving mothers and widows, militarised but pauperised oligarchs and frustrated uber-nationalists who believe Putin has not gone far enough in his wars. If there is a temporary peace he will need investment in post-conflict growth to stabilise his war economy or to intensify his other wars.

Hybrid War

Justice does need to be balanced with the realities of power. The post-1945 settlement was not a triumph of justice. Sovereign countries were cleaved apart and Eastern Europe was sacrificed to Soviet power. Europe must rouse itself to the reality that it’s no longer considered part of the American sphere of influence. Europe must now build its own military power to balance Russian bellicosity.

Russia will continue using grey-zone tactics including misinformation and disinformation to sow discord and undermine authority. It will also deploy: cyberattacks, electoral interference, economic coercion, diplomatic pressure, provocative military exercises, sabotage, arson, assassinations and drones.

These actions will remain below the thresholds that trigger legitimate conventional military responses or legal consequences, and it often be hard to attribute blame. Unchecked, grey-zone conflict will spread to new areas of increasing competition, including the arctic, as global warming opens up new routes and mineral opportunities, and space as we become more reliant on satellite technology.

Russia will not invade across the German plains but will work to promote and install a network of far-right, Putin-friendly autocratic governments, like Viktor Orbán’s Hungarian administration. More worryingly, the US NSS speaks of “cultivating resistance to Europe’s current trajectory within European nations.”

It also repeats far right rhetoric on civilisational erasure and approvingly cites “the growing influence of patriotic European parties.” Trump’s policies towards Europe are more aligned with Putin’s than they are with the majority of European countries.

Great power competition

The NSS states the US “cannot allow any nation to become so dominant that it could threaten our interests” and will “prevent the emergence of dominant adversaries.” This will eventually put the US on course for conflict with China.

The US-China economic relationship is too important for both Beijing and Washington for it to collapse completely, but it will be strained as China continues to assert itself. Tension in 2026 will likely be managed through economic warfare.

The biggest potential military flashpoint is Taiwan. China’s grey-zone noose will tighten around Taiwan, while the NSS states that America “will also maintain our longstanding declaratory policy on Taiwan.” China has its own challenges (managing deflation, slowing growth and industrial surplus), but as America retreats, there will be opportunities to extend Chinese influence.

Intervention or isolation

The NSS makes several references to the Monroe Doctrine, the foundational US foreign policy establishing US primacy in the western hemisphere. Recent pressure on Venezuela demonstrates that when there are economic benefits (oil and natural gas), national security issues (claims of nacro-terrorism) and ideological alignment (removal of a socialist regime) the US will still consider military intervention in its backyard.

The NSS states that its goals for the western hemisphere can be summarised as “Enlist and Expand.” In 2026 we will see the lengths to which America will go in order to “expand” its presence within its sphere of influence, particularly regarding states aligned with its strategic competitors.

Outside the Americas, any US intervention will need to be clearly in the national interest. This will include threats against supply chains, specifically for minerals and rare earths – those threats will escalate in 2026.

And if there is no national interest, the US engagement with the rest of the world will be determined by what happens to capture Trump’s attention. This means the resurgence of Islamist groups in Africa (including al-Shabaab in Somalia and al-Qaeda-linked JINM in Mali), the war in Sudan, and conflicts between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and, Afghanistan and Pakistan, may be left to spiral out of control. There may be photo opportunities and press releases about “deals”, but conflicts will lack detailed, sustainable peace plans as with Gaza and the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo

Despite the foreign policy pivot, American domestic politics still have the greatest single impact on geo-politics, making next November’s midterms perhaps the central event of 2026. An electoral endorsement for Trump could embed American First doctrine in US foreign policy for decades. Any attempt to influence the election, or a flat refusal by Trump to accept a poor result could throw America into a domestic crisis.