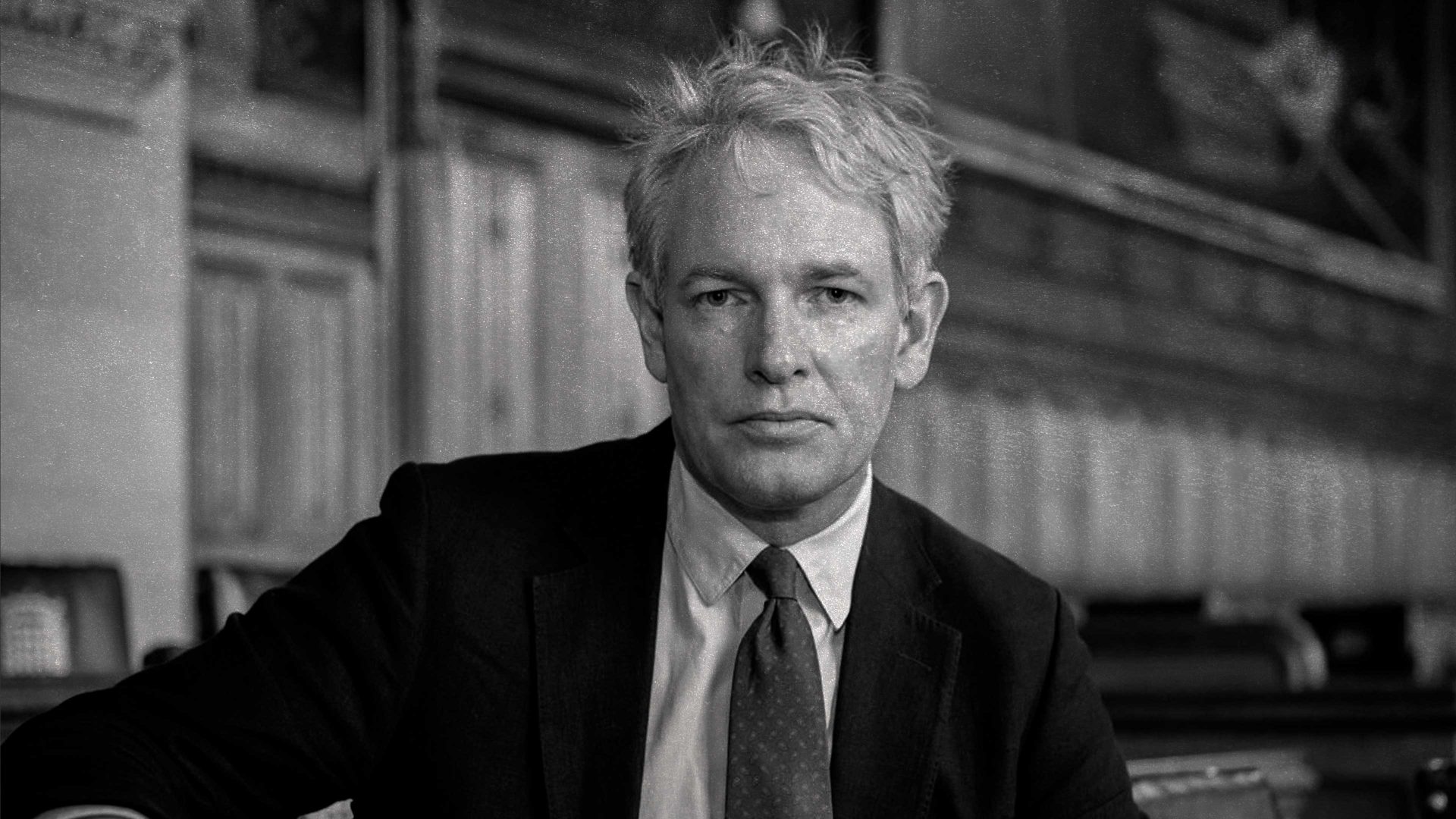

Just before Parliament rose for the summer Danny Kruger, the evangelical Christian MP for East Wiltshire, delivered an impassioned speech on the vital role of the Church of England in the life of parliament and the vital role of parliament in the life of christian England. Watching his remarks online, I counted three MPs in his audience. Other people counted as many as five. Either way it’s quite clear that his beliefs are exiled to the fringes of public life; but they may matter increasingly as the Starmer government struggles.

Kruger is one of a loose group of right wing Christians who believe that the collapse of the post-war settlement is inevitable; that the welfare state as we know it is doomed along with the international law. Good riddance to all of that, they’d add. They hope for a Christian revival in the ruins. This line of thought surfaces every year at the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship conferences funded by Paul Marshall where people like Douglas Murray and Jordan Peterson are treated as intellectual stars by right wingers from across the globe.

Kruger’s history of Britain is largely mythological: “Uniquely among the nations of the world, this nation – England, from which the United Kingdom grew – was founded and created consciously on the basis of the Bible and the story of the Hebrew people. In that sense, England is the oldest Christian country and the prototype of nations across the west… I speak of the common creed of our country, the official religion of the English and the British nation, and the institution – older than the monarchy, and much older than Parliament – which made this country.”

As history, this is an eccentric reading. The historian of Christianity Diarmaid MacCulloch says Kruger is “imposing some private agendas onto the reality of the past, like the historical half-truth that Christianity and Judaism are religions of the nation. That is to misunderstand both the nature of what nations are and the deep contradictions in both Christianity and Judaism about communal identity and what it means.”

But Kruger is not really interested in the grubby details of what actually happened or is happening today: “When I speak of the Church of England today, I am not speaking about the internal politics of the Anglican sect,” he said.

He has a sense of England in the same way as de Gaulle was animated by “une certaine idée de la France”, but de Gaulle’s example shows that the power of myths has nothing to do with their historical truth. What makes them powerful is not the solutions they propose, but the problems they bring to light.

The problem that Kruger and his friends identify is both economic and social – and, as he would see it, spiritual. It is that the world has no use for many of the people alive today and that Britain in particular has no use for many of the people living here. They serve no economic purpose. That is the root of Kruger’s horror at the assisted dying bill, or the complete legalisation of abortion. Both seem to him to deny any intrinsic worth to the powerless. Without a christian god to justify them, he argues, human rights and individual dignity are just fairy tales. If all value is relative – you are valuable to someone for some purpose, then only God can value or see a purpose in those whose lives are of no earthly use to anyone else.

This might seem academic, or even theological, in times of prosperity. But the time of feeling prosperous is over. Even if we assume that ever-increasing riches will bring ever-increasing happiness – and does Elon Musk act like a happy man? – ever-increasing riches are no longer a realistic expectation for most people in the west today. Just as industrialisation and globalisation destroyed the economic base of the traditional working class, it looks likely that AI will do the same to the middle classes, and the managers. That is a recipe for social conflict if not social breakdown.

Suggested Reading

The hard right will tear itself apart

One answer is some kind of gleeful identification with the strong and with the winners: fascism for the poor and nihilism for the rich. There is a lot of that in the online right as well as in the MAGA movement. Dominic Cummings and Elon Musk both use the gamer slang “NPC” (non-player character) to mean an unimportant creature who might be discarded without a thought.

Kruger and his fellow Christian reactionaries would reject this, and that’s a potentially important schism in the new right movement. Many of the more prominent evangelical Conservative MPs such as Philippa Stroud are committed within their churches to practical social work.

But all sections of the movement are united by a horror of Islam. If you believe that to be truly English you must be Christian – which seems to be Kruger’s argument – then Islam is a threat both to religion and to nationality, and Muslim immigration a threat to the existence of England. It’s very easy to see how this plays into the bloodthirsty racism of the mobs who would burn down asylum seekers’ hotels. Even if the intellectuals of the movement don’t mean for that to happen, that is how their ideas will be understood by demagogues and some of them at least will see racist violence as a form of understandable self-defence.

There is an irony here, in that Islam has a view of social cohesion and human dignity very similar to Kruger’s: he acknowledged in his speech that he had voted with Muslim MPs against assisted dying and against an enemy that he calls “woke”. His definition of that term is both confusing and confused: “It is a combination of ancient paganism, Christian heresies and the cult of modernism, all mashed up into a deeply mistaken and deeply dangerous ideology of power that is hostile to the essential objects of our affections and our loyalties: families, communities and nations. It is explicitly and most passionately hostile to Christianity as the wellspring of the west. That religion, unlike Islam, must simply be destroyed.”

You know roughly what he means: anything the Guardian is in favour of he is against. This kind of language is very common among the ideologues of Reform and it resonates with the kind of Anglicans who don’t actually go to Church. Research by professor Linda Woodhead, now at Kings College London, established that these cultural Church of England members were the backbone of the Brexit vote. Polling she commissioned in 2013 showed that 60% of Anglicans thought Britain had got worse since 1945. Most of those polled weren’t even alive then: their nostalgia was for a mythical golden age and the experience of Brexit has done nothing to diminish it.

A YouGov poll reported by the Conversation shows that Reform, with 38% of the vote, is now the most popular party among self-declared Anglicans.

Kruger may have spoken to an empty House, but out there on Youtube where his real audience matters, there are hundreds of thousands of people to whom he makes perfect sense.

Andrew Brown is winner of the Templeton European prize for religious journalism, and the Orwell Prize. He writes regularly on Substack