The US catholic church is deeply split over whether sex or economics matters more; whether abortion or immigration is the greatest challenge; and whether it should ally itself with the richest or the poorest.

The new pope, Leo XIV, and his predecessor, Francis, have both sided with the global poor. But a powerful network of American right wing multi-millionaires have worked for decades to portray their own interests as Catholic orthodoxy.

Now the ideological conflict has broken out of the US church and assumed global dimensions, after the pontiff told reporters that Donald Trump was “trying to break apart” the US alliance with Europe with his proposal to end the Ukraine war. The American-born pope added that the alliance “needs to be… very important today and in the future”.

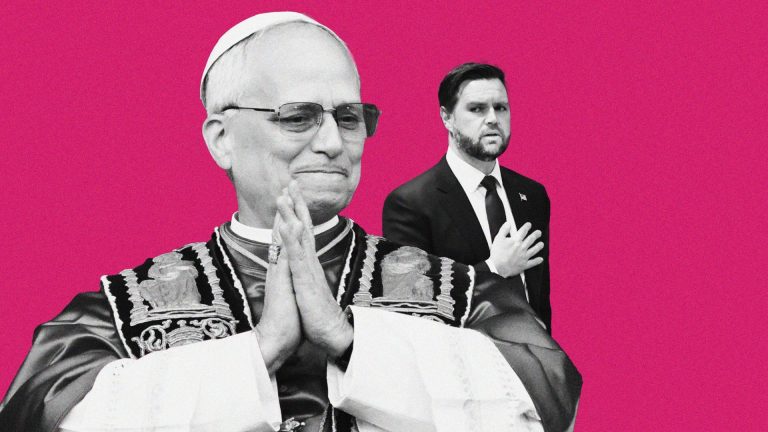

Before Leo became pope and was known as cardinal Robert Prevost, he had already been critical of the Trump administration. In January, vice-president JD Vance, a Catholic, gave an interview to Fox News in which he stated:

“There’s this old school, and I think it’s a very Christian concept by the way, that you love your family and then you love your neighbour, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens and your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritise the rest of the world.”

To this, the cardinal replied on X: “JD Vance is wrong: Jesus doesn’t ask us to rank our love for others.” Although Vance himself has said nothing directly about the pope, his patron and financial backer, Peter Thiel, has speculated that pope Leo may in fact be the antichrist.

More recently, the pope has also criticised the Trump administration’s apparent plans for a war with Venezuela. “It seems there is the possibility that there be some activity, even an operation to invade Venezuelan territory,” he told reporters. “I truly believe that it is better to look for ways of dialogue.”

Within the US itself, the struggle is at its sharpest in Chicago, the pope’s hometown, where a coalition of catholic clergy and nuns have sued the federal government over ICE’s refusal to allow them into its vast detention facility to pray with the inmates and offer them communion. They were even cleared away from the steps of the Broadview prison in September, where they had been praying loudly and in public, by armed men in camouflage uniforms working for ICE.

Immigration is now the central issue in the clash between the church and the White House. Vance said in January: “The greatest threat in Europe, and I’d say the greatest threat in the US until about 30 days ago, is that you’ve had the leaders of the west decide that they should send millions and millions of unvetted foreign migrants into their countries.”

The pope disagrees. He wrote in June: “The Church has always recognised in migrants a living presence of the Lord… migrants and refugees do not only represent a problem to be solved, but are brothers and sisters to be welcomed, respected and loved. They are an occasion that Providence gives us to help build a more just society, a more perfect democracy, a more united country… in every rejected migrant, it is Christ himself who knocks at the door of the community.”

That division is manifested in the recent attempts by the White House to shut down the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, led by Sister Norma Pimentel, known as “the immigrants’ nun”. The organisation helps migrant families in the border area, but the Department for Homeland Security has now cut all federal funding and is trying to debar the charity for six years. The White House accuses the charity of irregularities in its record keeping. Pimentel has pointed out that her charity deals with people the US government has already processed, and has dumped at the shelter.

In this way, a fundamental schism has opened up in the American moral landscape. The Catholic church finds itself on the faultline.

The Vatican has an internal system that has been running since the days of the Roman empire, and finds it extremely difficult to update itself. When the Catholic church does change, the old ways are simply put to one side, still there for anyone to examine but not used any more. Even this process is hugely complicated and requires a church council, drawing bishops from all over the world into years of deliberation.

The last major update took place at the Vatican II council, a series of meetings from 1962-65, each lasting up to 12 weeks. This council changed catholicism and was the point at which the Vatican came to terms with democracy, embracing religious freedom as an ideal. It also abandoned centuries of condemnation of the Jews.

The church largely replaced the Latin mass, standardised throughout the world at the Council of Trent 400 years before, allowing localised versions using vernacular languages. Perhaps more importantly, the priest now faced the congregation, rather than looking towards the altar – towards God.

Many people hated this, and with good reason. The traditional Latin mass was much more aesthetically pleasing than the translations, and if the Latin was incomprehensible this hardly mattered, for so is God, and the old mass brought people closer to this central mystery. But the new mass reflected the new direction of the church after the changes wrought by Vatican II.

Whenever there is change there are always disgruntled people, often the ones most invested in the old system.

In the decades after Vatican II, hundreds of thousands of men left the priesthood, most to get married, and attendance of mass collapsed across the west. Pope John Paul II and his immediate successor, Benedict XVI, spent much of their time trying to stop the decline, so much so that traditionalists hoped – and progressives feared – that the whole Vatican II experiment would be thrown into reverse.

Suggested Reading

Alastair Campbell’s Diary: The Pope vs JD Vance

Nowhere was the divide between traditionalists and progressives wider and more filled with hatred than in the US, where there are roughly 53 million Catholics – 20% of the population – and where even those who have left the church as adults would still form the third-largest denomination in the country.

I remember first becoming aware of the gap in the US church. I was in a pub with an American nun. I mentioned the pope, who was then the German Benedict XVI. In response, she gave a spontaneous Nazi salute. On the other side of the US divide, a small group of very rich men, most notably Timothy Busch, a Californian lawyer whose firm specialises in estate planning for wealthy clients, and Tom Monaghan, who made his fortune from Domino’s Pizza, combined a theological rejection of Vatican II with a political commitment to unfettered free-market capitalism.

The contrast with the current pontiff’s thinking couldn’t be more acute. The first document he published as pope stated: “In a world where the poor are increasingly numerous, we paradoxically see the growth of a wealthy elite, living in a bubble of comfort and luxury, almost in another world compared to ordinary people… a culture… that discards others without even realising it and tolerates with indifference that millions of people die of hunger or survive in conditions unfit for human beings.”

Meanwhile, a new kind of conservative Catholic devotee has grown in influence in the US over recent decades by funding private universities, think tanks, and magazines. They have also nourished the networks that helped to place six conservative Catholics on today’s Supreme Court, where they have overseen the abolition of the federal right to abortion.

This brand of Catholicism merged seamlessly first with the Republican Party, and now with the MAGA movement. Tim Busch wrote in May: “Donald Trump’s administration is the most Christian I’ve ever seen… His vice-president, JD Vance, may very well be the most articulate Catholic politician in the modern world.”

MAGA Catholicism believes in minimal government interference in the economy and maximum state control over women’s bodies – and yet the public appetite for this is negligible. A recent Pew Foundation survey found that 83% of US Catholics disagree with the ban on artificial birth control; and only 13% think abortion should be entirely banned, despite decades of pro-life preaching; 25% think it should be entirely legal, and a majority think it should be legal in most cases.

They also want female priests and married priests. Those are changes that the Vatican cannot deliver without crashing the whole system, and most Catholic lay people are content just to ignore what is said from the pulpit when they disagree with it.

When it comes to unfettered global capitalism, papal teaching has been opposed to that since at least 1891, when Pope Leo XIII published Rerum Novarum, an encyclical that justified workers’ rights. The present pope, Leo XIV, chose his name in homage to that document. In 2016 his predecessor, pope Francis, published Laudato Si’, an extraordinary document that framed the climate crisis as the product of economic exploitation of both people and the natural world.

The hostility between Francis and the MAGA Catholics was open. When he died, they made every effort to ensure that his successor would reverse his policies.

The election of Robert Prevost as Leo XIV was therefore a disappointment to much of the American hierarchy, even if he was one of their own. In his previous job in Rome he had helped Francis to sack a Texan bishop, Joseph Strickland, whose outspoken attacks on Francis had made him a darling of the Catholic right. And, in the way of modern religious arguments, Strickland had more followers on Twitter/X (145,000) than he had Catholics in his diocese.

Leo clearly continues Francis’s hostility to unfettered markets. In his first teaching document, he wrote: “There is no shortage of theories attempting to justify the present state of affairs or to explain that economic thinking requires us to wait for invisible market forces to resolve everything. Nevertheless, the dignity of every human person must be respected today, not tomorrow, and the extreme poverty of all those to whom this dignity is denied should constantly weigh upon our consciences.”

Within the US church, demography and money are now pulling in different directions. The big money is all on the MAGA side, but the congregations are increasingly immigrant, and especially Hispanic. The proportion of white Catholics has dropped by 10% since 2007; their Hispanic replacements are younger, poorer, and now feel vulnerable to arbitrary deportation. Eighty per cent of white Christians have parents born in the US – among Hispanics, around 80% have parents who were not.

In early November, the US Catholic bishops elected their leader for the next three years, and by a margin of 128-109 they chose Paul Coakley of Oklahoma City. In 2017 he endorsed a notorious critic of Francis who had accused the pope, quite groundlessly, of covering up a case of sexual abuse.

But even Coakley has spoken up strongly for immigrants and against mass deportations, and America’s bishops voted overwhelmingly to pass a motion that denounced the vilification of immigrants. It stated: “We are grieved when we meet parents who fear being detained when taking their children to school and when we try to console family members who have already been separated from their loved ones.”

These are strong words, but very general. Dawn Eden Goldstein, a Catholic writer and church lawyer, says: “I think there’s a weakness of will here. When the bishops criticised the policies of the Biden or Obama administrations, they named the presidents whose policies they were attacking. But they will never mention president Trump by name when they are attacking his policies.”

Though the US clergy may be shy, the pope is more forthright. “It is a programme that Donald Trump and his advisers put together,” he said recently of Trump’s peace plan for Ukraine. “He is the president of the United States, and he has the right to do that.

“It has a number of things in it that, while perhaps many people in the US would be in agreement, I think many others would see things a different way.”