I noticed them immediately, growing flamboyantly out of the rubble-strewn pavements of Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Taller than a man, with fat, sap filled leaves and a robust stem, they dot the roadside through the desert and flourish, heavy with dusty-green fruit the size of tennis balls, in the hot, dry air.

Ensconced in a three truck convoy traveling from the northeast coast to the capital, Khartoum, where the White and Blue Niles meet in central Sudan, I learned from our driver, Badr Eldin, that this native plant is known locally as ushar and while Calotropis procera looks benign, the fruit is just rind filled with air and the leaves contain a toxic, milky sap so bitter that not even animals can bear to eat them.

“There is something symbolic about the contradictions of Sudan and its natural resources,” said my fellow traveller, Adel Soliman, the last director of BBC Arabic Radio as he gazed at the vast desert landscape whizzing past outside.

“So much of what appeared to be good for its people – or was brought in to benefit them – became very harmful or even worse, turned out to be their enemy.”

The straight 900km highway that links the sea with Khartoum is relentlessly flat, its two lanes witness to a constant duel between impossibly laden, often rickety trucks and impatient local drivers, a game of chicken not for the faint hearted. Suddenly, surviving a road trip felt as nerve-wracking as reporting from a country torn by a civil war.

Outside, enormous cloudless skies framed rust coloured desert sands, vast, alien rock formations and faraway mountains in silhouette. Tiny, fragile settlements of huts fashioned from wood and rags rush by, lonely goat and donkey herds, the occasional camel among mole-hill mounds of long abandoned, hand-mined gold digs.

And everywhere, the ubiquitous mesquite bush, this one an import from South America in the early 1920s ostensibly to combat desertification and provide animal fodder. The Sudanese have nicknamed mesquite the “devil tree” as its deep, difficult to eradicate roots swallow everything in their path, native plants, precious agricultural land and even water reservoirs.

Chatting in the car as Badr Eldin slid the Land Cruiser in and out past phalanxes of trucks, pretty much everything we saw served to illustrate the disastrous, paradoxical fortunes of the modern Republic of Sudan.

Sudan is the third largest producer of gold in Africa, where it is largely extracted by small-scale hand mining and controlled by competing factions, fuelling conflict in the ongoing civil war. Salt is also an important export but this too has been disrupted in the conflict with starving Sudanese forced to resort to eating weeds boiled with dangerous, non-iodised salt to survive.

Meanwhile the paramilitary Janjaweed forces that were imported originally by the Sudanese military to bolster its national defences have morphed into the brutal, Rapid Support Forces (RSF). This group of largely foreign, Arab-supremacist mercenaries turned on their masters in December 2023 and unleashed the latest, devastating civil war on the Sudanese people, plunging them into widespread famine.

The republic of Sudan may have won its independence from joint Anglo-Egyptian rule in 1956 but it has been entangled with many of the African continent’s most complex problems ever since. Osama Bin Laden made the affluent Al-Riyadh quarter in Khartoum his home in the 1990s and the long-lived insurgency in what we now know as South Sudan, independent since a referendum in 2011, enmeshed many neighbouring nations and saw millions of lives lost.

In 2003, president Omar al-Bashir used Arab militias, including the notorious Janjaweed, to wage ethnic war, resulting in the Darfur genocide which claimed an estimated 300,000 lives.

My travelling companion, the British author and Middle East expert, Peter Oborne, reminded me that the al-Bashir regime ravaged the country for decades with its drive for both power and wealth. This was one of many reasons why the RSF leader, Mohamad Hamadan Daglo, also known as Hemedti, and the commander of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan worked together to remove the civilian government, which fell in a military coup of 2019.

The duo ruled in tandem relatively smoothly until the Sudanese government tried to integrate the RSF into the military. That set off a wave of violence that has killed 150,000 people in less than three years.

Today, the RSF is funded by the United Arab Emirates, and is accused by the Sudanese military and human rights groups of genocide. The wave of mass killings began in western Darfur in 2023 – it continues in the besieged city of El Fasher today.

Three hours into our journey we were preparing for a first stop in the township of Haiya when we were told that we had to continue on for unexplained security reasons. Desperate for a loo break, we begged to be allowed out quickly only to be met by winds so hot and ferocious that the dreaded drop toilet hidden behind a head high wall became a welcome refuge.

Over the next several hours we passed through Ad-Damir and alongside the road where trucks carried their cargoes of 21st century goods. The camel trains moved languorously alongside, still following the ancient trade routes that head inland from the sea.

In Atbara, a town bristling with hundreds of tuk-tuks, we fell onto plates of chargrilled chicken wrapped in flatbreads, eating with our hands and downing cold freshly made lemon and mint juice. Alcohol is illegal in Sudan. A bag of Sudanese oranges bought on the roadside turned out to be inordinately fragrant if much drier than what we are used to and were a much-enjoyed accompaniment on the long drive.

Suggested Reading

When looters arrived in Sudan’s National Museum

Near Ad-Damir where an enormous electricity and power station shimmered on the horizon, we saw more trucks carrying people and furniture, occasionally with a young soldier armed with a machine gun riding on top of the cabin. It was hard to work out whether the guns were for security, or if these were just soldiers hitching a lift home. At a petrol station further on, I noticed a smaller truck with only women inside while a young man in camouflage fatigues and with a machine gun sat up top. I took a covert picture. A UN statement the following day expressed concern about the trafficking of women and girls abducted from areas controlled by the RSF.

More than half a million people have been forced from their homes and displaced since the RSF siege in El Fasher began in May, moving to camps in neighbouring Chad and on the northeastern border with Egypt. It is estimated that 12 million Sudanese refugees have fled since the war began.

Passing through Shendi, culture and beauty briefly superseded talk of war, when the dramatic shapes of the Meroë pyramids appeared in the distance. Sudan has 255 pyramids, nearly twice the number in Egypt. Built by the Nubians as tombs for the royalty of the Kingdoms of Kush, they are found in three other sites as well as at Meroë around 200km northeast of Khartoum.

Seemingly untouched by tourism, they rise out of the enormous dunes with an unforgettable power and majesty and have lost none of their imposing presence despite the destruction wreaked in the 1830s by the Italian treasure hunter, Giuseppe Ferlini. His finds, mainly gold and ancient jewellery, were sold to King Ludwig I of Bavaria and are now in museums in Munich and Berlin.

Our facilitators insisted that we should arrive in Khartoum before nightfall to abide by the current military-imposed security restrictions. We made it just in time, and we passed through Bahri under a blood red sunset. Exhausted, we were shown to rooms in a small apartment block in Omdurman, itself a major city on the west bank of the Nile directly opposite and slightly northwest of Khartoum proper. The following morning, sunlight streamed through a patch of silver film stuck to my window. Examining it, I realised someone had used it to seal a bullet hole.

It is difficult to describe the utter devastation of Khartoum. It’s known as the triangular capital because it is made of three cities, including Omdurman and north Khartoum. But now the once thriving commercial and historic heart of the capital is a blackened, burned-out shell, its streets filled with plastic bags whirling in the wind like tumbleweed, accompanied by the eerily cheerful sound of birdsong.

Three months on from Omdurman’s liberation by the Sudanese Army, residents are cautiously returning to the elegant, wide treelined boulevards of the city centre. But there are still plenty of military checkpoints, which are set up to protect what little is left from looters.

Hospitals, apartment blocks, modern skyscraper hotels, embassies, banks, ornate colonial buildings, even the city’s mosques have been torched into oblivion. The Sudanese national museum, once the proud home of half a million artefacts tracing Sudan’s history from the mysterious kingdom of Kush through to the arrival of Islam, has been looted into nonexistence.

In the lobby of what was once the high rise, five-star Meridien hotel, an armoured car complete with an anti-aircraft gun looks like a rusted prop from a war movie amid piles of debris. The hotel pool is empty and our guides tell us the military only recently cleared it of dumped bodies. Nearby, the state of the art Al Baraha Medical City Hospital, commandeered by the RSF for months, was looted of all medical and diagnostic equipment and torched as they left: nothing remains, just the skeletons of a couple of dialysis machines and the oxygen taps they couldn’t rip out of the walls.

Across the river, the Sudanese national broadcaster’s compound in Omdurman along with its radio and TV studios, decades of interviews, documentaries, songs and music in audio archives, all lie in ruins. The broadcast vans have been burned, trashed or stolen. Only the film archive kept in a basement below ground was somehow miraculously left untouched.

The Sudanese minister for culture, Khalid Ali Aleisir told us the RSF did not just want to kill the people of Sudan, its children and its elderly but to “erase our history, our heritage and our culture too”.

In a refugee camp not far away, Mubarek, 10, was playing happily with his friends until a colleague asked him where his parents were: “The RSF killed my father” he said, his wide, welcoming smile quickly replaced by tears. “My mother is over there, she is sick,” he said, pointing to a row of low shacks on the edge of Omduram. “They beat us. They came to the market, took our food and asked us if we knew Sudanese soldiers living in our street. We were scared. I was crying all the time”.

Khartoum resident, Heba, 26, fled her home city not long after fighting began, embarking on the long, grim road trip we had just completed from Port Sudan in search of safety.

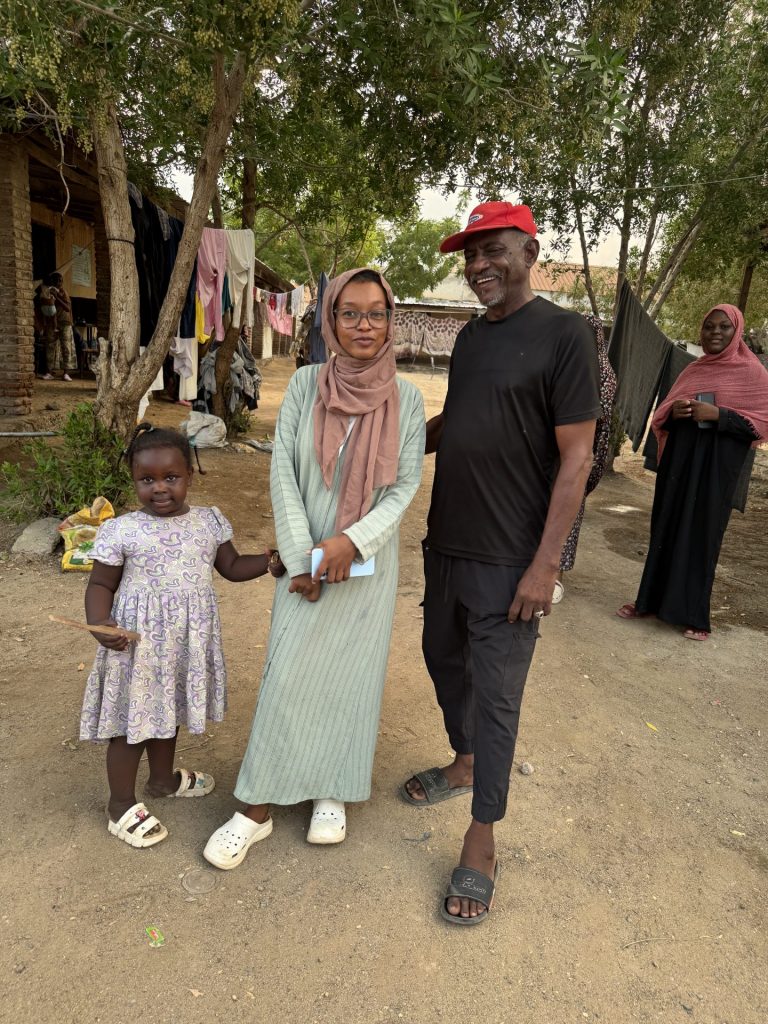

She lives in a shadeless, makeshift camp sharing a cluster of huts fashioned from wood and blankets with several hundred others. Like many, Heba had no desire to speak about the violence she witnessed. Rather, she proudly told us that she was a graduate in information systems, and had learned her excellent self-taught English through watching YouTube, reading novels and “talking to natives on social media”.

Measured, stoic, cheerful, she was unconvinced by Sudanese army reassurances that her home city was safe from the RSF. A couple of days after our visit, she sent me a WhatsApp message: “I hope one day I can go back there and live better life with my family but… it’s not just about being back, it’s about being back better and stronger and building a version that’s going to add to the world and to humanity”.

As we prepared for our own return journey, I wondered yet again why this terrible war has stayed under the world’s radar for so long. Sudan is often referred to as the “forgotten war”. The war here does not feature high on anyone’s list of priorities.

Standing on the highway that reaches deep into the desert, it seemed clear to me that the path toward peace cannot be achieved by military victory alone. Sudan could very well collapse into an even worse state, drawing in its neighbours and triggering wider regional chaos. If there is a recovery and a return to stability and democracy, that will take a long time to achieve.

The nation’s future will ultimately be forged by the young, bright and altruistic generation encapsulated by Heba or by Ahmed Salih, the brilliant young man who chose not to flee his country but to stay. Now he acts as a guide and teaches people like us about Sudan. Because we must all learn about Sudan. So much western diplomatic capital has been spent in negotiations over Gaza and Ukraine – but not Sudan. The moral implications of that are becoming impossible to justify.